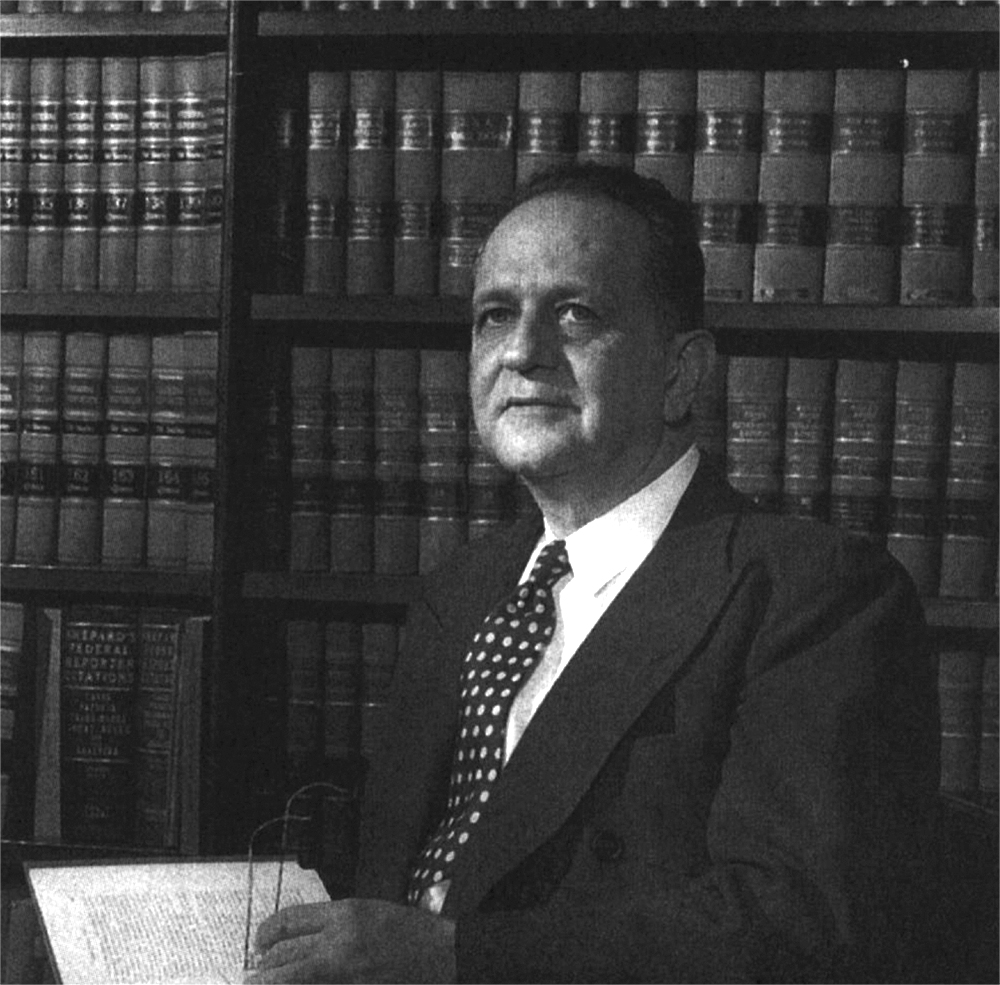

WE NEED NOT INTEGRATE TO EDUCATE, CHARLES J. BLOCH, Jewish Segregationist

March 2, 1959

* * *

“ . . . no federal court can ever compel the Governor and the Legislature (of Georgia) to institute, maintain and operate a system of public schools in which the races are mixed.”

* * *

Charles Bloch, Macon attorney, received his higher education at Louisiana State University, University of Georgia and Mercer University. He is first Vice President of the States’ Rights Council of Georgia, Editor of the Georgia Bar Journal, member of the Standing Committee of the American Bar Association on the Federal Judiciary, Fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers, chairman of the Rules Committee of the Supreme Court of Georgia, member of the Advisory Board of the American Bar Association Journal, Fellow of the American Bar Foundation, former president of the Georgia Bar Association, former member of the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia, former chairman of the Judicial Council of the State of Georgia, Georgia delegate to Democratic National Conventions 1932, 1944, 1948 and 1952, and author of the recent nationally acclaimed book States Rights, The Law of the Land.

***

States’ Rights Council

1522 William-Oliver Bldg.

Atlanta 3, Georgia

I was admitted to practice in Georgia in 1914. Whenever I think of that I think of my younger grandson who lives up in Nashville, Tennessee. We were visiting up there not long ago and he thought it was his sweet duty to entertain his grandfather, and so he said, “Papa, were you born in the last century?” I said, “Well, come to think of it I was.” “Well, how many years did you live in the last century?” I said seven. He said, “Well, did you know Noah?” “No, he was a little ahead of me, but not very much.”

The so-called segregation decisions w[e]re handed down by the Supreme Court on May 17, 1954. Almost 5 years have elapsed. Georgia’s public schools remain segregated. There are those of us who have determined that they shall remain segregated. There are others who seem equally determined, and perhaps more vociferously determined, that they shall become integrated. And there are those who profess to be concerned only with the question of whether Georgia’s children shall continue their education.

Perhaps their concern really is that Georgia has not surrendered its rights as a sovereign state. So they, some 3 months ago, began a campaign of harassment. A campaign having as its object the causing of anxiety to the parents of Georgia.

“How are your children to be educated?” they write continually. Bear in mind they are writing not only for Atlanta readers, not only for Georgia readers, but they are writing for readers in Ohio and in Miami, Florida. Naturally, you are concerned with the question of the education of your children. But, I say to you, bear in mind these facts.

The question of the education of your children in the schools of Georgia has not yet been decided by any court. What the Supreme Court of the United States said on May 17, 1954 did not decide it. What the Supreme Court said in 1955 did not decide it. What the Supreme Court said in the Little Rock case last September did not decide it. What the Virginia courts recently said did not decide it.

We hear so much of this phrase—“the law of the land”—that we are violating the “law of the land”. Now my friends, I ask you this question, if the law of the land was promulgated by the Supreme Court of the United States on May 17, 1954, if the law of the land was then promulgated, then every school board in every one of the 159 counties of Georgia has been violating the “law of the land” for 4 years and 9 months.

And I wonder why the Attorney General of the United States, or the Solicitor General of the United States, or some District Attorney has not prosecuted them if they were violating the law of the land. The palpable reason is that they are not violating the law of the land.

So far as the question can be decided by the courts, it will be decided when, and only when, Georgia’s laws are construed by a court having jurisdiction of the parties and the subject matter.

Over at my alma mater, the University of Georgia, we have a Latin motto, which freely translated is “Not only to teach but to find out the reasons for things”. All my life I have been taught and have tried to teach “find out the facts”, so I say to you in considering the problem, “find out the facts”. Do not rely on facts that are handed out to you in some brainwashing way.

I refer particularly to a leaflet that was sent to me not long ago headed, “Do you know the law about schools, what does the Supreme Court say, what does the Georgia Constitution say, what do Georgia laws provide, what do federal court rulings following the May 1954 decision say?”

It seems as if it was gotten out by an organization known as the League of Women Voters. Now, if there are any ladies in the audience who are members of the League of Women Voters, I would suggest to you that the next time you go to a meeting of the League of Women Voters you suggest to them that they find out the facts because somebody is feeding them law that isn’t correct.

I won’t spend much time on this pamphlet, but I would, seriously, like for some lady in the audience who may be a member of that organization to call the organization’s attention to the case of Borders vs. Rippey, cited in that leaflet, which they say was decided on July 23, 1957, and they say was decided by the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit at that time; suggest to them that they look at the latest decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in that case, decided on a reappearance of that same case, which came from Dallas, Texas, on December 27, 1957.

And the next time they get out a leaflet, put in that leaflet what the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit, sitting down at New Orleans, said then.

Now, there are other more or less minor errors in that pamphlet. For instance, whoever prepared it for the good ladies who put it out made a mistake when they quoted from the case of Kelly vs. the Board of Education of the City of Nashville, because I happen to be right familiar with what happens up in Nashville, Tennessee.

If the League is interested and will drop me a line, I will call attention more in detail to just exactly what error they have fallen into about that case.

In ascertaining the facts, don’t rely on the opinions and imaginings of any columnist, even though the column might be on the left hand side of a front page.

If you will but learn the facts you will find out that the problem, too, is not a spiritual or a moral one.

I had sent to me a resolution prepared by—or for—a ministerial organization recently, in which there is a sentence which I quote. “The closing of the public schools is an extremity that must be avoided at any cost.” That is the quotation from that document.

When I read that my mind went back some 17 years to the time when the Germans were bombing London, and a truly great representative of the Anglican Church, the Reverend Michael Coleman, came to Macon and spoke at Christ’s Church there. I will never forget that evening.

After his speech there, under the auspices of “Bundles for Britain”, I believe it was, he was entertained at the home of some friends of mine. We were sitting around the fireside talking, and he was telling us more about the bombing of Britain, and while he was telling about the Germans flying over in these planes and the way the British boys went up to meet them and drove them off, a lady in the small group interrupted and said, “I believe in peace at any price.” He turned slightly toward her and said, “I feel very sorry for you,” and then turned and resumed his talk.

I can’t help but feel sorry for anybody, minister or not, who thinks that the closing of the public schools is an extremity that must be avoided at any cost. I can’t help but wonder when I read that sentence, when I first heard that sentence, what would have happened to the world if the British people had been taught 19 years ago, “peace at any price.”

If it were a spiritual – moral – religious problem, it would have long ago been settled by the men of God who have graced the pulpits of the cathedrals and the churches and the synagogues of Georgia during the past century[.]

If the segregation of the races in public schools had been irreligious, un-Godlike, those eminent divines would long since have so told us. They would not have needed a Warren or a Frankfurter or a Black or a Douglas to have taught them anything about religion.

Don’t be brainwashed, my friends, into thinking that the South has been driven to defend the wrong side of a moral or spiritual issue. (Do those words sound familiar to you? They were over in that left column.) [T]he problem has no such facets as that.

It originated as a political problem, pure and simple, conceived, born and nurtured in that struggle for power known as politics. It has become a politico-legal problem.

To know the real facts you have to go a long way back. You must go back to 1619. The colony of Virginia was settled by the British in 1607. Twelve years later Dutch slave traders brought African slaves to Virginia and sold them. That was the beginning of the institution of slavery on this continent.

As the colonies of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut and all the rest of the original 13 were successively settled, slavery became prevalent among them[.] The colored people in their native land had been accustomed to a warm climate, so they thrived in the warmer Southern states. They were more adapted to work in the fields of the South than they were in the industries of the North.

But, while the number of slaves in the South was far greater than in the North, the North was far more active in furnishing and operating vessels engaged in the slave trade. The New Englanders conducted the traffic resulting in the sales in the South.

The 13 original colonies, separated from the mother country, first combined under the Articles of Confederation; and then in 1789 formed the union supposed to be regulated by the Constitution of the United States.

It is hard for us to realize that the colonial period of American history extended over a period of 182 years, while only 170 years have elapsed since the formation of the union. But when that Constitution was signed, the contracting parties, the states who signed it, at least in three instances, recognized slavery as a legal institution. Not only that, but the Constitution provided that the migration or importation of such persons as any of the states might think proper to admit must not be prohibited by Congress until 1808. The slave traders were given 20 years within which to wear out their ships.

And when that Constitution was adopted they put into it what was known as the Tenth Amendment—the last of the Ten Amendments which comprise the Bill of Rights. “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively or to the people.”

Acting under that clause—that reserved power some states abolished slavery, others continued it. And, strange to say, though the state of Massachusetts abolished slavery, she retained separate schools for white and colored children.

In 1849, one hundred and ten years ago, 12 years before the beginning of the War Between the States, the first case arose in these United States respecting, regarding, deciding the question of whether a state had the right to segregate children in the public schools.

And, the supreme judicial court of the state of Massachusetts, in a case in which Charles Sumner—who afterwards became the arch-enemy of the South—in which Charles Sumner was counsel, decided that although the Massachusetts Constitution provided for equality of the races and equality of all people, that the state of Massachusetts had the right to segregate children in her public schools.

Now, about that same time, these slave trading ships had worn out, so suddenly up there in New England the cry of abolition arose and a war ensued. About all that that war proved was the South could not withdraw from the union.

We in the South, your forefathers and mine, didn’t fight that war for the purpose of determining whether slavery was legal or not. The war was fought because the states of the South thought that the Constitution of the United States was a contract from which they could withdraw when they thought it was broken. President Lincoln and the North said that they couldn’t. It took four years of bloody war to decide that they couldn’t. But, that was all that the war decided. They couldn’t withdraw.

Now, shortly after the end of the war the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, and that’s the amendment that’s causing all of the trouble today. “No state”, it says, “shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law[.]” Now, my friends, I don’t want to go into too legalistic a talk with you, but I do want you to get this point in learning your facts—and these are facts.

Mark that phrase well, “No state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law.” That amendment was adopted, or was supposed to have been adopted, in 1868. Within five years after its adoption, the Supreme Courts of the States of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, California, Nevada and Missouri decided that despite that amendment those states had a right to operate public school systems in which the white and colored races were separated.

Some five or six years later the Supreme Court of New York decided the same thing. That was so much the “law of the land” in those days that not one of those cases was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. And the question never reached the Supreme Court of the United States until 1896, when in the famous case of Plessy vs. Ferguson, the Supreme Court of the United States established the separate but equal doctrine, applied not to public schools but to transportation, railroad cars, the “Jim Crow” laws.

And, it wasn’t until 31 years later, in 1927, sixty years after the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, that the Supreme Court of the United States, headed by that great jurist, that great American and ex-president of the United States, William Howard Taft, unanimously held that it had been decided so many times that the states of this union had the right to segregate the races in the public schools that it was no longer an open question in that court.

Now that was some sixty years after the end of the war. And with that green light shining from that case decided by Chief Justice Taft, the states of the South, emerging from reconstruction, emerging from the war period, began the construction of a magnificent public school system.

My friends, I noticed in the paper today, some gentleman speaking on this subject at a church yesterday afternoon said that if we in the South had provided better schools for the colored people 20 years ago that this crisis never would have arisen. That is an utter damnation of the Supreme Court of the United States if that is true, because is the Supreme Court of the United States punishing us for not having furnished better schools 20 years ago?

But I wonder if that young gentleman realizes that it took this beloved Southland of ours some 60 years to emerge from the War Between the States, to emerge from reconstruction? When I was a boy some 50 – 60 years ago, people didn’t have money enough for schools for white children, much less for colored children, but in my county we established them and did the best we could for them then.

And in the year 1927 when that case was decided by Chief Justice Taft, I wonder if my friend who is a member of the Legislature knows what the total appropriation of the state of Georgia was for the operation of the whole state in 1927 and 1928. Fifteen million dollars. And we were called, I say “we” because I happened to be a member of that legislature, we were called the spendthrift legislature because we appropriated 15 millions of dollars, when Dick Russell was speaker, to operate the whole state of Georgia.

Much has been made of the fact that a distinguished Georgian has called the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the segregation cases an accomplished fact. Well, it’s an accomplished fact that I am standing on this platform talking to you, but that doesn’t mean that I will remain here forever.

The Supreme Court decided Brown vs. Topeka. That does not mean that the court cannot be shown that it was wrong. Four of the nine who decided it have left, one by death, three by resignation. It is our earnest hope that in a proper case we will be permitted to demonstrate to a trial court and to the Supreme Court, that Brown vs. Topeka, the segregation case, is basically and in the light of experience wrong. Wrong legally and wrong morally.

A court, which in the Texas primary case admitted error, ought not to be averse to admitting error when error can be mathematically demonstrated. A court which in the Girard College case recently, tacitly admitted error, may do so again.

By every legal means we seek to have the court correct a grievous wrong, and in so doing we defy no one, we flout nobody; we point out error and ask its correction. But, if the decision should not be changed, what then?

Nine years after the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, Georgia adopted a state Constitution as soon as she could get rid of the carpetbaggers of that day. That Constitution of 1877, as amended in 1912, has this provision in it, and I beg you to follow it closely, I’m quoting: “There shall be a thorough system of common schools for the education of children as nearly uniform as practicable, the expenses of which shall be provided for by taxation or otherwise. The schools shall be free to all children of the state, but separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored races.”

That provision required a system of public schools but that provision was eliminated from the Constitution in 1945. And, my friends, they can’t blame Dick Russell for eliminating it, and they can’t blame Herman Talmadge for eliminating it, and they can’t blame me for eliminating it. Governor Ellis Arnall eliminated it.

When Ellis Arnall was Governor of Georgia in 1945 he appointed a Constitutional commission which wrote a new Constitution, and in the place of that provision which I read to you there was substituted this, and this is in your present Constitution of Georgia:

“The provision of an adequate education for the citizens shall be a primary obligation of the State of Georgia, the expense of which shall be provided for by taxation. Separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored races.”

So, as the fundamental law of the State of Georgia—her Constitution—provides today, there is no requirement for a system of common or public schools. The people of Georgia changed that fourteen years ago. The people of Georgia now say to the State, its Governor, its legislators, “It is your primary obligation to provide an adequate education for the citizens. What is an adequate education, you, Governor and legislators, determine. But if you determine to have a system of public schools, separate schools shall be maintained for the white and colored races.” So if the Supreme Court of the United States should ever decide that the provision for separate schools is invalid, then Georgia has no constitutional or legal right under her present Constitution and laws to operate a public school system at all.

The fact and the law are simply this: if the Constitution of the United States is so construed as to prevent Georgia from operating separate schools, Georgia has no right to operate any schools. Georgia’s Constitution and laws do not permit her to operate schools in which the races are mixed.

Now lest you be confused by brainwashing and so-called legal doctrine emanating from the imagination of columnists, while the Constitution of the United States is, as every schoolboy knows, the Supreme law of the land, that supreme law of the land cannot compel Georgia to operate a system of public schools in which the races are mixed. That supreme law of the land, as construed by a court, may someday compel Georgia to abandon her public school system, but no federal court can ever compel the Governor and the legislature and the people of Georgia to institute, maintain and operate a system of public schools in which the races are mingled.

And don’t let anyone delude you into thinking that the federal government has compelled Virginia to operate mixed schools. It has done no such thing. It has decreed Virginia must operate mixed schools if it operates any schools, and Virginia’s highest court has construed her constitution so as to compel the operation of public schools.

That, my friends, is the manifest important difference between the situation in Virginia and the situation in Georgia. That, my friends, is the reason why I went to such deliberate, painstaking pains to point out to you the difference between your constitution of 1877 and the Ellis Arnall constitution of 1945. Georgia’s constitution provides no such thing as Virginia’s.

Georgia’s constitution obligates the state, the Governor and the legislature to provide an adequate education for the citizens of Georgia. So if the federal court should say to Georgia, “You can’t comply with the obligations of your constitution by providing a public school system in which the races are separated,” Georgia, her Governor, her legislature will then be confronted with the question, “How will we now provide an adequate education for our children? Will we submit a constitutional amendment to the people eliminating that requirement from our constitution?”

In deciding whether to repeal that provision, in deciding whether to repeal the laws forbidding the mixing of the races, Georgia’s Governor, Georgia’s legislators and the people of Georgia—if and when they vote on a constitutional amendment—will have the benefit of a great deal of experience in other states and in the District of Columbia.

We may decide that it is not for the best interests of our children, and our children’s children that the public schools must be kept open at any cost. We may realize that it isn’t simply a question of whether colored children and white children attend the same school, associate in the same classrooms. We will, of course have to decide whether a public school system is so essential to education that our children must be subjected to the hazards, the psychological disturbances, the very real physical dangers which today surround little girls and little boys in the schools of the District of Columbia, of New York, of Philadelphia, of Milwaukee. Dangers which caused there to be debated in the general assembly of the State of New York this very day legislation empowering the principals of the schools of the State of New York, the Corso Bill, to administer corporal punishment to those people who are causing the trouble in those schools up in New York, which we are asked to emulate.

But, we’ll have to find out more facts before we make a decision, for if the federal government can force us to mix our schools rather than to close them then the federal government will decide who will teach in those schools. The federal government will decide what is to be taught in them. Already, the Supreme Court has deprived New York and New Hampshire of their right to remove Communists from the faculties of the schools and colleges of those states.

That the South is not alone in her fears of what is happening, I call your attention to the action of the House of Delegates of the American Bar Association, meeting in Chicago one week ago. After a two years’ study, the committee of lawyers, composed of members from New York, Florida, Virginia, North Carolina, Iowa, New Hampshire and other states, recommended the prompt enactment of legislation to eliminate obstacles to the preservation of our internal security.

In other words, to wipe out decisions of the Supreme Court coddling Communists. That report was overwhelmingly adopted by the House of Delegates. The lawyers of America realize now what some of us have been preaching so many years. I quote from that resolution:

“Upon the bar of each state, primarily falls the duty to protect and defend its constitutional form of government, and courageously to lead and soundly to advise the peoples and their government. By their very training and experience, none more than lawyers should be aware of the dangers and the menace of international Communism, and, therefore, none is more responsible for the protection of the free world.”

I have been called recently, and I quote, “on the make,” end of quote. At the risk of being called that again or perhaps even worse, I tell you that this business of school integration, the harm it will do, the friction it has created is another one of the dangers and menaces of international Communism.

As one slight evidence of that, I call your attention to what is happening in Congress this very day. In the so-called National Defense Education Act is a requirement that students receiving loans swear not to overthrow the government.

On December 15, last, Secretary Arthur S. Flemming of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, stated that that oath serves no useful purpose. That is the federal department, the federal bureau, which will operate your public schools if you permit them to be federalized.

Federal Education Commissioner Derthick, on February 19th, agreed with Secretary Flemming’s views. Those are the men who will control the selection of the faculties of federalized schools.

Why anyone would refuse to swear not to overthrow the government of the United States of America is beyond my comprehension. But, so many things are being preached and taught today that are beyond my comprehension.

Now, if we should not change our constitution and laws so as to permit integrated schools, how will we fulfill our obligation to provide an adequate education for our children? That is the question which Senators Russell and Talmadge, Governor Vandiver, Lieutenant Governor Byrd and scores of dedicated Georgians, legislators and non-legislators, have been sincerely studying these many months. That is THE QUESTION.

For, I say to you, that in my opinion, the great majority of the people of Georgia will never vote to abolish segregation of the races in the public schools of Georgia. And, I say to you that the great majority of the parents of Georgia will let their public schools be closed and REMAIN closed before they will ever vote to place them in the hands of a federal bureaucracy.

And, I say to you that the descendants of the people who, in the 18th century revolted against the tyranny of a British king, who in the 19th century lost their all rather than to submit to the tyranny of an organized majority, will not in the 20th century sacrifice their children upon the altar of partisan politics to satisfy an organized minority.

The people of Georgia will never inflict upon their children such an education at such a price.

So, I give you my opinion that there is not going to be any integration of public schools in Georgia. And we need not have integration to have education.

In our study of the question of how to fulfill our obligation to educate without integrating, we have been greatly handicapped. If you were teaching your young son to play baseball you might very safely say to him: “Son, to be a strike, a pitched ball must cross some part of home plate and be between the batter’s shoulders and his knees.”

Now you would feel pretty badly, wouldn’t you, if your son came home one evening and told you: “Dad, I came up to bat today with two outs and the bases filled and the umpire called me out on strikes. I didn’t strike at pitches below my knees, but he called them strikes, and when I asked why, he said ‘Oh, I’ve changed the rules; they’re too hard on the pitcher’.” So, we who are conscientiously and sincerely trying to advise those whose primary duty it is to furnish an adequate education to your children are greatly handicapped.

If the pole marking the foul line would just stay even where it is now, we can fairly safely advise. If the pole isn’t moved while the batted ball is in flight we can, with some certainty, advise.

So, assuming that legal principles will no further have to bow to psychological doctrines, I, speaking for myself, am firmly of the opinion that the state of Georgia can fulfill her constitutional obligation of partially providing an adequate education for her children without ever integrating a single school anywhere in Georgia.

I, for one, know too that token integration is a snare and a delusion. If anyone ever really and sincerely believed that token integration would satisfy the political machine known as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, certainly that belief was dissipated by the resolution of that organization in Florida last week.

I, for one, am definitely of the opinion that Georgia has a right to make grants to parents for the education of their children and that the parents may use those grants to defray the tuition of the children without the school’s thus becoming a state school.

But, naturally, you ask, “Suppose you have those grants, what school would the children attend? Where are the buildings which would house our children?” We have only to look at Front Royal, Virginia, to see the result of courageous planning by people who do not believe in peace at any price. Arlington, Alexandria, Norfolk are not the Virginia which we, your fathers and mine, knew. Front Royal is truly represent[at]ive of those people who composed the Army of Northern Virginia.

But we do not have to content ourselves with converted homes or parish houses or churches. If the federal government, the federal courts succeed in compelling the closing of our schools, the State of Georgia, the cities of Georgia, the counties of Georgia, the local units of school administration, the owners of what had been public school buildings may be vested with the perfect legal right to sell those schools, absolutely divesting the state of any interest in them.

With those provisions for grants in aid, divestiture of what had been school properties and provisions for deductions from income tax amounts expended or donated for educational purposes, the state will have exhausted its powers, under the Constitution as now construed, to make provision for an adequate education for its citizens.

I had been concerned at the time it was proposed, planned and adopted about the tax deduction feature, until it occurred to me that the federal government permits deductions from gross incomes for amounts donated by taxpayers to churches and other religious institutions. If the federal government can permit such donations without there thereby being a violation of the First Amendment, certainly the state can permit them without becoming involved with the Fourteenth.

But now, when the state or one of its subdivisions divests itself of what had been school properties, who shall buy them, or who will buy them? Private industry. Private capital. Private citizens then must fill an existing vacuum and form first a statewide private school foundation, and secondly, in each county at least one private school corporation.

There is no novelty about private schools, you know. There were private schools before there were ever public schools. Private primary schools can thrive and prosper as well as private secondary schools.

Those industries, those citizens who have feared and are fearing the ever increasing spread of paternalism, the ever increasing concentration of national power, may now have their opportunity.

This private school foundation must be headed by men and women who have the confidence of the people of the whole state. It should be the guide for the formation of the county corporation. A free people, wishing to remain free, will supply the organization details. The state of Georgia will go just as far as it can under existing Constitutional doctrines toward providing an adequate education for its citizens without integration.

The State of Georgia—of whom do you think when you hear the phrase, “the State of Georgia”? I think first of a man whom I first met 33 years ago when I was privileged to serve with him as a member of the General Assembly.

I see him as a youth in his 20’s, serving as Speaker of the House of Representatives. I see him as a young Governor of Georgia, reorganizing our state government. I see him establishing the Board of Regents for the governing of the University System of Georgia. I see him in January, 1933, taking the oath as Senator from Georgia in the Senate of the United States.

I see him serving through the depression of the 30’s, the war of the 40’s and the troublesome years which have followed. I see him as the South’s hope for president of the United States in 1948 and 1952. I see him shunted aside in favor of lesser men because of the place of his birth, and I sit with him again as I hear him say, “I would not exchange my Southern birthright for any presidency”.

I see him respected in the Senate, fighting the battles of his country and his state; ever courageous, ever sincere, ever honest, ever seeking the answer to one question and one alone . . . what is right? I speak, of course, of Dick Russell, and I am privileged to bring you a message from him to you here tonight. I quote from a letter which he wrote Mr. Wesley just a day or two ago, with a copy to me giving me permission to quote from it as I might desire. I cite this, my friends, as an example of the kind of man you’ve got working with you and for you, trying to help you solve this problem.

“It is heartening”, said Senator Russell, “to see that the citizens of Northside Atlanta, who believe in preserving segregation in the schools, are taking steps to make your voices heard and your views known. In recent months we have witnessed a deliberate campaign to mislead the people of Georgia into believing that they face the immediate choice of integrated schools or no form of education for their children.

“The object of this campaign is to persuade the people to swallow the fatal bait of token integration. Of course, there can be no such thing as token integration. This is merely a device of the race mixers to obtain total and complete integration.

“The people of North Carolina are now discovering that the N.A.A.C.P. and their fellow integrationists will never accept mixed schools on a token basis. I commend the Northside Association to Continue Segregated Education for your refusal to surrender your children to token integration and for your determination to see that Georgians continue to run Georgia schools.”

I think of another man, too, now also a Senator from Georgia to the Senate of the United States. I think of him gracefully bowing to the decision of the Supreme Court of Georgia on March 19, 1947, and vacating the office of Governor. I see him come back to that office, borne by the overwhelming vote of his people.

I see him in the face of shouts of “demagoguery”, battling for what he knew was right and what has been proven to be right. I see him manfully facing and answering his critics. I see him chosen by his people again with unparalleled unanimity as their Senator.

I see him enter a scoffing Senate and day by day grow in dignity and ability and in the respect of his fellows. I see him, too, ever seeking the answer to the question, “what is best for my people? What is best for my Georgians?” He knows that in the answer to this question is the answer to the greater question, what is best for America?

For he knows that the last bulwark of Constitutional government is in the South and in Georgia.

And I think of our ten able representatives from ten separate regions of the state, and of our Lieutenant Governor and of the senators and representatives of the counties of the state in the General Assembly of Georgia. They are leaders ever battling for the good of Georgia.

And, finally, I think of the man who is our chief executive, Governor Ernest Vandiver. I see him preparing himself throughout his life for the position he fills today. I see him valiantly and intellectually ready to face any crisis which may confront him.

And when I think of those people, I think that we of the State of Georgia should be proud of them—proud of their leadership, cognizant of their innate strength and courage. And, I think that we should repel any effort to undermine them, but, on the contrary, we should say to them, “We have confidence in you, your ability, your integrity, your leadership, your desire for the right. We know that you are earnest and sincere in your efforts to prevent the calamities of the integration of our public schools, your efforts to provide an adequate education for Georgia citizens. We shall help you.”

Let us make a pledge to them: We shall help you to provide education without integration. We shall help you to let the politicos, whether labeled Republicans or labeled Democrats, whether they be from New York or Illinois, Michigan or Ohio, California or Minnesota, to let those politicians know that the education of Georgia’s children in Georgia’s business and Georgia’s citizens will attend to that business.