Judah P. Benjamin: The Jewish Face of Black Slavery

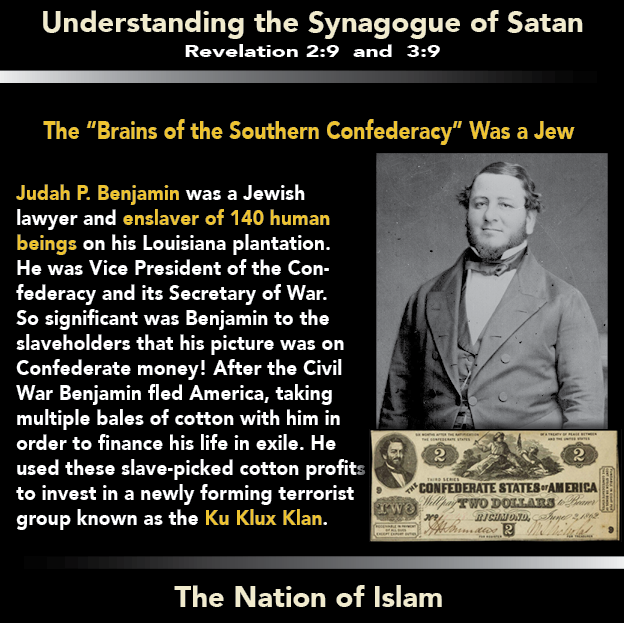

The most significant and powerful Jew in American history was the rabidly pro-slavery senator from Louisiana named Judah Phillip Benjamin (1811–1884). He was born in the British West Indies and brought up in Charleston, South Carolina. He owned a sugar plantation in Bellachasse, a town south of New Orleans on the Mississippi River. And there he forced at least 140 Africans into slavery in its operation making Benjamin the largest Jewish slave owner in American history. Of course, many a Jewish slave trader bought and sold hundreds and hundreds of human beings in the course of their businesses, but Benjamin bought them not to profit from their commerce but to work them day and night on his sugar plantation.

But Benjamin was not merely a plantation master, in the Civil War era it was Benjamin who led the call for secession of the southern states from the Union in order to maintain the profits of free slave labor. Benjamin was described by Harvard professor Richard S. Tedlow as:

“The most important American-Jewish diplomat before Henry Kissinger, the most eminent lawyer before Brandeis, the leading figure in martial affairs before Hyman Rickover, the greatest American-Jewish orator, and the most influential Jew ever to take a seat in the United States Senate…”

Yet he believed Blacks to be no better than farm animals. It was Benjamin the senator who contended that it was more humane to whip and brand the self-emancipated Black man (they called them “runaways”) than to imprison or transport him. Ohio’s abolitionist senator, Benjamin F. Wade, denounced Benjamin as “[a]n Israelite with the principles of an Egyptian.” When the South seceded to become the Confederate States of America, its new president Jefferson Davis chose Benjamin to be the Confederacy’s Secretary of War. Benjamin was no mere functionary. Yale’s David Brion Davis points out that “Judah Benjamin wrote Davis’ speeches, issued executive orders, called cabinet meetings, and virtually served as ‘acting president’” as he “sought to destroy the Union in order to keep four million blacks enslaved.”[2]

Yet he believed Blacks to be no better than farm animals. It was Benjamin the senator who contended that it was more humane to whip and brand the self-emancipated Black man (they called them “runaways”) than to imprison or transport him. Ohio’s abolitionist senator, Benjamin F. Wade, denounced Benjamin as “[a]n Israelite with the principles of an Egyptian.” When the South seceded to become the Confederate States of America, its new president Jefferson Davis chose Benjamin to be the Confederacy’s Secretary of War. Benjamin was no mere functionary. Yale’s David Brion Davis points out that “Judah Benjamin wrote Davis’ speeches, issued executive orders, called cabinet meetings, and virtually served as ‘acting president’” as he “sought to destroy the Union in order to keep four million blacks enslaved.”[2]

It was Judah P. Benjamin who arranged for the Confederate government to secure a massive loan from the French Jewish banker Emile Erlanger allowing them to procure everything they needed to extend the war for more than a year, adding countless thousands to the dead and maimed. According to Judith Fenner Gentry,

“Without the Erlanger loan money, purchases of arms, supplies, and ships in Europe would have stopped, and Confederate credit would have been ruined.”

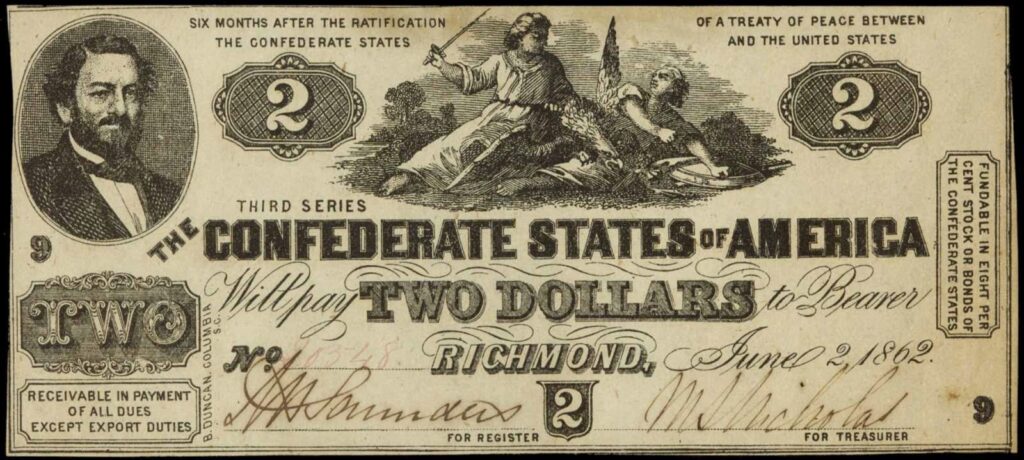

Erlanger negotiated the deal with Benjamin, whose service to the slavocracy was so significant that his face was affixed to its money, along with a violent image of the South striking down the Union.

After the Civil War dismantled the slavery system, most American Jews were found to be in full accord with the aims of the Ku Klux Klan. Here, and with a measure of pride, a B’nai B’rith leader reveals that the KKK’s Gentile “emissary” was sent across the ocean to appeal to a Jew for the financing needed to establish the most notorious racial terrorist organization in American history—and was successful:

“Shortly after the Ku Klux Klan was founded, Bishop Richard H. Wilmer, an intimate friend of the Dragon of the Alabama realm, met Judah P. Benjamin, then an exile, in England. The former ‘brains of the Confederacy’ was told of the plight of the South and about the hopes of the KKK to rid the South of its incubus. Wilmer told him that the Knights needed horses and ‘dry-goods’ (uniforms) in order to frighten the Negroes. Benjamin, trying to recoup his fortunes, was financially unable to aid, but he borrowed money to supply the Ku Klux Klan with saddles and arms and dispatched Wilmer with the needed funds.” [Jewish Tribune, Sept. 14, 1928]

Rabbi and historian Dr. Bertram W. Korn pointed out the irony that Judah P. Benjamin’s honors were “in some measure dependent upon the sufferings of the very Negro slaves he [and others] bought and sold with such equanimity….Few politicians are as consistent in anything as Benjamin was in support of the ‘peculiar institution’ [slavery].” Even Jewish historian Morris U. Schappes has written that “history has found Benjamin guilty and his cause evil.” But Dr. Herman Frank, writing in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle [Oct. 9, 1925], represented another point of view:

“The fact that Benjamin financed the Klan in 1867 cannot but speak for his good intentions and breadth of mind.…It is not by mere chance that chief among the contributors was a London Jew, Judah P. Benjamin, to whom no profits whatsoever could accrue through the operations of the Klan in the United States. In this respect, Benjamin showed himself a genuine Jew, worthy of the best Jewish traditions which call for devotion to principles of good will and loyalty that survive the strife and stress of partisan conflicts.”

A recent book about Judah P. Benjamin by James Traub and published by Yale University explains Benjamin’s role as a slave owner and the Jewish role in slavery:

“[S]lavery for [Benjamin] was a necessary and profitable practice rather than a holy cause….Our instinct to hold Judah Benjamin to a higher standard because he was a Jew ignores the near-universal ownership of slaves among Southern Jews of means, not to mention the unwillingness of Southern Jews to rock the boat in which they sailed to a life of prosperity and freedom. Even Northern Jews hesitated to do so. The authors of an American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society report in 1853 asked why the ‘Jews of the United States have never taken any steps whatever with regard to the Slavery question.’ The answer: ‘As citizens, they deem it their policy “to have everyone choose whichever side he may deem best to promote his own interests and the welfare of his country.”’

“That was a fair-minded summation, for Jews were as divided as Christians on the question of slavery. Some Reform Jews were ardent abolitionists, while others were not. Jewish businessmen and laborers who depended on trade with the South typically sided with the Democrats against the anti-slavery Republicans. Others found sanction for slavery in the Old Testament. In a celebrated address in New York on January 4, 1861, Orthodox Rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall argued that slavery had existed before the flood and was nowhere outlawed either in the Mosaic code or even in the New Testament. ‘How are you denouncing slaveholding as a sin?’ he thundered at abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher. Raphall insisted that the coming war could be avoided if only both North and South accepted the biblical practice of according slaves rights ‘not conflicting with the rights of his master.’”

Author James Traub then describes Judah P. Benjamin’s knowledge of and enthusiasm for the business of sugar production, and the horrific, inhuman conditions for the Black slaves:

Reading [Benjamin’s] account, one imagines the exuberant Benjamin bent over drawings with Packwood and Rillieux. Yet virtually every single person around them would have been a slave. It was widely believed in Louisiana that no white man could survive the fierce heat and humidity, the flies and the disease, and the backbreaking labor of sugar cultivation. The very word “Louisiana” struck terror in the hearts of slaves elsewhere. As Jacob Strayer, a former slave, wrote, “Louisiana was considered by the slaves a place of slaughter, so those who were going there did not expect to see their friends again.”

In the 1840s a group of slaves on a Florida plantation staged a mass escape when they learned they were to be transported to Louisiana for sale. In his history of the Louisiana sugar plantation, Richard Follett writes, “The grueling rigors of the sugar industry placed an unfathomable strain on the human body.” At the New Orleans slave market, sugar planters were known to almost exclusively purchase brawny young men of eighteen to twenty-five; no one else could manage the work.

Because cane grows in swampy soil, prodigious labor was required to clear the ground for a new field: slaves felled vast trees, tore up the roots, burned the logs, plowed the flattened earth, drained the surrounding land, erected levees against the river. What’s more, unlike cotton, sugar required year-round, non-stop work. Solomon Northup, the free black man who was sold into slavery and later wrote Twelve Years a Slave, worked on several Louisiana sugar plantations and wrote an extensive account of their operation. Between January and April, Northup explains, three teams of work gangs planted the cane (though one crop of seedlings lasted for three years). The first cut short lengths of cane reserved from the year before, the second planted the cane in prepared beds, and the third covered the cane with earth. This continued until April. For the next four months the hottest time of the year-slaves would hoe the earth around the cane three times over, bringing fresh soil to the roots. The smallest children weeded the ground or burned felled logs; boys carried water to the field hands. Other gangs drained the soil and reinforced the levees. Slaves spent the ensuing months making repairs and cutting and carting wood, the fuel for the giant kettles.

A cane harvest, and the subsequent grinding, required a concentrated fury of work. Three slaves armed with a long, tapering cutlass formed up along the cane brakes, and as they proceeded down the row sheared off the branches, cut off the tops, severed the cane at the root and placed it beside them, where it would be scooped up by younger slaves following be hind with a wheelbarrow. The imperative to cut all the cane before frost set in compelled an industrial pace; slaves who fell behind would be whipped. Others fell ill from the heat or exhaustion, or suffered injuries from the wicked blade. The mortality rate was fearsome. The moment the cane was harvested the process of manufacture began. During this final period, which could last two months, slaves were expected to work eighteen hours a day. Slave children stood along a vast belt, feeding the cane into the rollers. Other slaves fed the fires, filled the hogs heads with refined sugar, and tended to the equipment. Indeed, one of the striking features of the sugar plantation is that slaves served as engineers and mechanics, highly skilled jobs for which they would have been well compensated as free men. By the end of the year, sugar had been dispatched to the market and the time had come for new planting.

We do not know what it was like to be a slave at Bellechasse. [Benjamin biographer] Pierce Butler spoke to several of Benjamin’s former slaves, who testified to his relative benevolence. That may be, yet Benjamin could not have avoided the ugliest aspect of slavery: the buying and selling of humans. The mortality rates on sugar plantations necessitated a regular replenishment of human stock. Cane work also required far more men than women, some times in a ratio as high as seven to one; ordinary reproduction could not supply enough workers. Because slaves represented capital in human form, masters typically did their own purchasing. New Orleans was the slave-market capital of the South: tens of thousands of slaves passed through the central mart at the corner of Chartres and Esplanade, in the French Quarter. Others were sold in specialty markets in the St. Charles Hotel and elsewhere in town, including a few blocks from Benjamin’s offices on Camp Street. Frederick Bancroft, an early slave historian, writes of New Orleans, “Slave-trading there had a peculiar dash: it rejoiced in its display and prosperity; it felt unashamed, almost proud.”

In the slave pens, Judah Benjamin would have come to know something else that perhaps he would rather not know: that children were torn from the arms of their mothers, and husbands taken from wives. And when these dreadful partings occurred, these very human people reacted with grief and rage, just as white people did. “His passions and feelings may in some respect not be as fervid and delicate as that of the white, nor his intellect as acute,” Benjamin had said in the Creole case; “but passions and feelings he has.”

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.