A Jew TORTURES A Black Man: Recollections of a Runaway Slave — 1838

“I have often wished that I was a dog, they seemed so much better off than we.”

(Reprinted from The Emancipator, September 13, 1838)

Narrative of “Jim”—a Freedom-Seeking Black Man

I was born in South Carolina, at a place called “Four Holes,” about 25 miles up in the country from Charleston. My father was an outland man. He died when I was very small and I can just remember him. My mother died when I was a baby. I am about twenty years old and have been a slave all my life. I was owned by a widow woman named Smith till I was about fourteen…

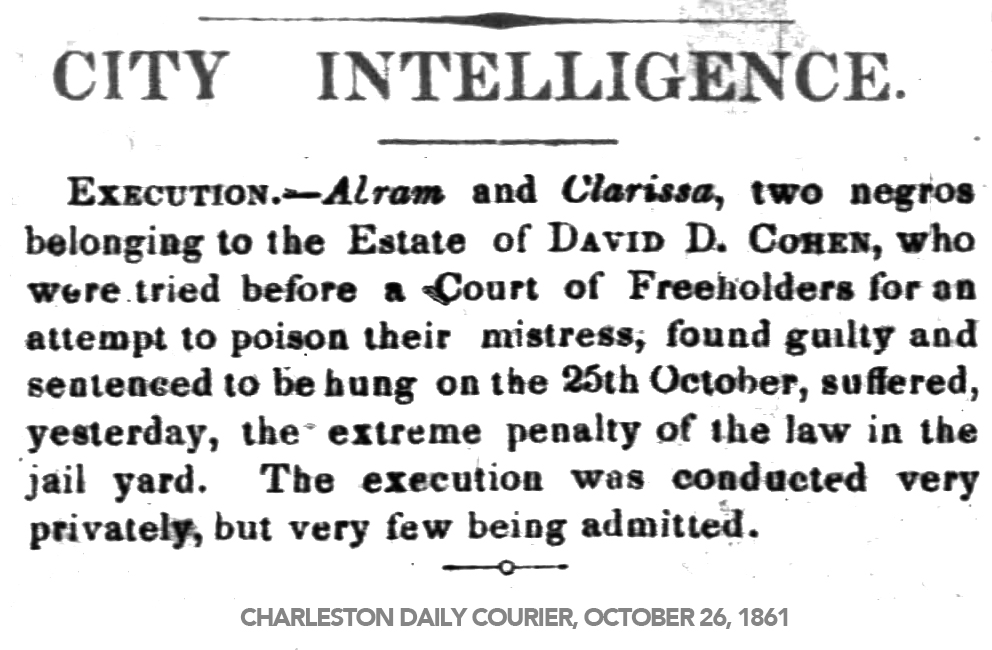

Mr. Smith sold me to Davy Cohen, a Jew who lived on Ashley River, about 12 miles from Charleston. He was very rich and some years made such great crops of rice that he was not able to sell it all, and stowed it away in his barns. He raised besides a great quantity of hog meat; but he would not eat any himself nor let us have any. Sometimes we would steal a hog and carry it into the fields and roast it, and share it, and then hide it in the ground and get it as it was wanted. We stole only four in the two years I lived with him. He was in the habit of walking about at all hours of the night to find out who stole wood, or turnips, or hogs, or any thing else.

One time he found out that an old man, named Peter, had been stealing wood down by the river. He took it and hid it in the woods, calculating to carry it off the next Sunday. Every Sunday five or six of us had to row the boat-load of wood to Charleston to market. We started at midnight so as to get there by breakfast time Sunday morning. Master rode in his chaise and got there early to sell it. Sometimes instead of wood we carried watermelons, and ducks, and eggs, and had a good boat load of all kinds of fruit and other things. People do a great deal of marketing in Charleston on Sunday. Our boat was always loaded Saturday evening, and Peter’s plan was to put the stolen wood on top of master’s, and throw it off in some back place in town, and sell it when he found a chance. There were only five or six sticks of it.

When master missed his wood, he took ten of the slaves and carried them to the camp, and after he had whipped three or four of them, Peter’s boy got frightened and informed against his father. They carried Peter to his hut, and tied him up so that his feet could not touch the ground, then tied his feet together and put a great log between them, to keep him stretched tight. Then they whipped him till he fainted twice in the rope. They did not leave off whipping him till midnight. One of the men that kept the door said he “guessed Peter would have to be buried the next day, master whipped him so much.” They always say “a nigger is not whipped to do him good, unless he faints.” They say “cut into him; a nigger hasn’t got any feeling—there’s no feeling in a nigger’s hide—you must cut through his hide to make him feel!”

After they had done whipping Peter, they gave him a dose of salts and put him in the stocks, down in the cellar, where it was so dark, you could not see your hand before you. When any one is put in the stocks a chain is put around his neck with a padlock on it, and the end of it is fastened to a beam of the house. His feet are put into holes between two pieces of wood, which are then bolted down close to his ankles—his hands are tied, and he has to lie down on his back, without being able to move any part of his body except his head. Sometimes slaves are kept in the stocks two or three weeks, and whipped twice a week, and fed on gruel, because they run away or steal.

Slaves have to go to the fields after being whipped, when their skin is so cut up that they have to keep all the time pulling their clothes away from the raw flesh. Sometimes they are so bad off that they can’t wear any clothes on their back at all, and have no dress but a piece of cloth tied around their bodies. In this case, they have to put boughs on their heads and shoulders to keep away the flies. A great many of them never have a hat, and the sun and rain will turn their hair all brown or red, just like flannel.

We were allowed one pair of shoes in a year. They were given to us in the winter, but we used to keep them till summer, for the heat was worse than the cold. The sand was so hot that if we buried an egg in it in the morning, it would be cooked by ten or eleven o’clock, and our feet got all blistered and burnt up if we went without shoes. If we carried water with us into the fields, we dug deep holes and buried it, to keep it cool.

Our houses were nothing but pole pens, built square, and covered with pine and cypress bark, without any floor. In wet weather the rain would beat in upon us, the same as though we were out doors. When we got a chance, we brought home boughs and laid them on the roof, but the rain still came in. We had no beds but hay or grass, or clapboards, and sometimes no covering but our old clothes, made into patchwork. If they ever gave us a blanket, we had to make it last four or five years. Often we did not have beds at all, but slept in the ashes. We built our fires in the middle of the house, and never moved the ashes, so that there was a great heap, and when we came home we prepared our ash-cake, and put it into the hot ashes to bake, and then laid down there ourselves and slept till the horn blew in the morning. Then we got up and brushed the ashes off, and took our cake or potatoes and went straight to work.

When I lived with Cohen I was hostler, but had to work in the field besides. When they wanted to go anywhere in the carriage, they called me and made me pull off my old rags, and put on the clothes which they had in the house.

One night towards the last of the week, our allowance was gone and we were very hungry. So I and two others went into the musk-melon patch and took three or four melons apiece. The next day they measured our tracks and then measured our feet, and whipped some of us, till one told who did it. There was a man and woman besides me. The man’s name was Reuben. They carried the man into the woods, where they had four stakes driven into the ground, and stretched him out and fastened him there. The driver whipped him for a long time. Afterwards they washed him down with brine and then put him in the stocks. I was tied round a log. They tied me as close as possible with strings round my neck and hands and feet. They put a cap on my head and drew it down closely over my face. It covered my whole face, and was tied under my chin, and was not taken off till the whipping and washing were all over. After whipping I was put into the stocks. They tied the woman up to a tree, and made her hug round it. She was whipped more than I was, though I was whipped badly enough. They put her into the dungeon, a dark hole under the house.

The same driver whipped us all. After he was done he complained that he was tired. All drivers are black men, and slaves. They have to do as the overseer says, or they will get whipped themselves. They live in houses apart from the rest. Their business is to blow the horn in the morning for us to get up, and then drive us all day to get as much out of us as they can. They get praise when we do a good day’s work, and that makes them drive us harder and cut and lash us, so as to make us do as much another day.

The morning after our whipping, we all had to go to work, as if nothing had happened. I was so sore I could hardly do anything. I had to leave my row and go off over the fence a great many times, and towards night, when I saw I could not get my task done, and knew I should be whipped again, I made for the woods, and at midnight went as far as I could down the country. I there fell in with some more runaways, who had a camp in the swamp, and staid with them till I was caught. It is very common for slaves to run away into the woods after being badly whipped. They are forced to, for they cannot do their tasks, and so they have to stay in the woods till they get well. Sometimes they stay there five or six weeks till they are taken, or are driven back by hunger. I have known a great many who never came back; they were whipped so bad they never got well, but died in the woods, and their bodies have been found by people hunting. White men come in sometimes with collars and chains and bells, which they had taken from dead slaves. They just take off their irons and then leave them, and think no more about them.

They keep a great many hounds on purpose to hunt runaways. They call them “nigger dogs.” Alfred Smith had about fifty of them. They teach them to run colored people when they are pups. They used to make me run off a good ways, when I was very small, and then send the pups on my tracks. I thought it was fine sport. Sometimes they called the hands from the field and made them run round the house and climb trees, with the dogs after them. They cooked every day a great pot of hominy for them, and the victuals left from master’s table was always given them. When I have passed them in the yard eating a good piece of meat, I have often wished that I was a dog, they seemed so much better off than we.

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.