Jewish Scholars Quoted on the American South

Dr. Ira Rosenwaike, “The Jewish Population in 1820,” in Abraham J. Karp, ed., The Jewish Experience in America: Selected Studies from the Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (Waltham, Massachusetts, 1969, 3 volumes), vol. 2, pp. 2, 17, 19:

“In Charleston, Richmond and Savannah the large majority (over three-fourths) of the Jewish households contained one or more slaves; in Baltimore, only one out of three households were slaveholding; in New York, one out of eighteen….Among the slaveholding households the median number of slaves owned ranged from five in Savannah to one in New York.”

Jacob Rader Marcus, United States Jewry, 1776-1985 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989), p. 586.

“All through the eighteenth century, into the early nineteenth, Jews in the North were to own black servants; in the South, the few plantations owned by Jews were tilled with slave labor. In 1820, over 75 percent of all Jewish families in Charleston, Richmond, and Savannah owned slaves, employed as domestic servants; almost 40 percent of all Jewish householders in the United States owned one slave or more. There were no protests against slavery as such by Jews in the South, where they were always outnumbered at least 100 to 1….But very few Jews anywhere in the United States protested against chattel slavery on moral grounds.”

Rabbi Bertram W. Korn, “Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865.” (See also Korn’s American Jewry and the Civil War)

“It would seem to be realistic to conclude that any Jew who could afford to own slaves and had need for their services would do so….Jews participated in every aspect and process of the exploitation of the defenseless blacks.”

One of the most respected rabbis in America, Max Lilienthal of Cincinnati, “agreed with most of his colleagues that the abolitionists were incendiary radicals who were bringing the nation to the brink of disaster.” Lilienthal delivered an after-the-fact sermon on April 14, 1865, in which he publicly apologized for not having been anti-slavery until Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. When a lay member of the “chosen” community wrongly believed Lilienthal to be an abolitionist he sent to Lilienthal a picture of the rabbi with this note scrawled across the front: Sir: Since you have discarded the Lord and taken up the Sword in defense of a Negro government, your picture that has occupied a place in our southern home, we return herewith, that you may present it to your Black Friends, as it will not be permitted in our dwelling. Your veneration for the Star Spangled Banner is, I presume, in your pocket, like all other demagogues who left their country for their country’s good. I shall be engaged actively in the field and should be happy to rid Israel of the disgrace of your life. Be assured that we have memories; our friends we shall not forget. Should you ever desire to cultivate any acquaintance with me, I affix my name and residence, and you may find someone in your place who can inform you who I am. Jacob A. Cohen New Orleans, La., C.S.A.

Rabbi Bertram Korn says quite directly:

“The Jews of the Confederacy had good reason to be loyal to their section. Nowhere else in America – certainly not in the ante-bellum North – had Jews been accorded such an opportunity to be complete equals as in the Old South. The race distinctions fostered by slavery had a great deal to do with this, and also the pressing need of Southern communities for high-level skills in commerce, in the professions, in education, in literature, and in political life. But the fact of the matter is that the older Jewish families of the South, those long settled in large cities like Richmond, Charleston and New Orleans, but in smaller towns also, achieved a more genuinely integrated status with their neighbors than has seemed possible in any other part of the United States then or now. Political recognition, social acceptance, and personal fame were accorded to Jews of merit.”

Writing of the Jewish interests in colonial Georgia: Paul Masserman and Max Baker, The Jews Come to America (Bloch Publishing Co., “The Jewish Book Concern”, 1932), p. 84:

“The Jews prospered. They could trade and barter freely, and before long they were among the leading traders in the colony. But in 1740-41 the trustees put a stop to slave traffic in the colony. This was such a severe blow to business that most of the Jews left the colony and only three families remained: the Shetfalls, the Minises and the DeLyons. The congregation, of course, was dissolved.”

Barry E. Supple, writing of the Jews in the Business History Journal:

“For most of them the Civil War brought prosperity at least to some degree. Even where, as in the case of Straus and the Lehman brothers, operating within the southern economy, they had to bear the brunt of commercial dislocation and general insecurity, there might be some counterbalancing benefits.”

He called the period “one of relatively uncomplicated prosperity” for the Jews.

George Cohen, The Jew in the Making of America (Boston, 1924), pp. 84-5.

“For the most part they had acquired wealth and owned numerous slaves whom they exploited for the development of their resources. Their prosperity and long tenancy had won them prestige equal to that of the non-Jewish natives, and they were not only completely at home amid their surroundings, but, naturally, supported and sanctioned the institutions that had been so propitious to them, providing them with wealth, position and comfort. Like other wealthy Southern land and slave owners they were convinced that their financial stability depended upon maintaining the services of the negro slaves. It is, therefore, hardly surprising that they became staunch upholders of the slavery system, in their unwillingness to relinquish these personal benefits.”

Stanley Feldstein put it in his book The Land That I Show You.

“Jews also engaged in the dehumanization process—the making a thing of a human being.”

Robert Leo E. Turitz and Evelyn Turitz, Jews in Early Mississippi (Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1983), p. xvii.

“What sociological phenomena would lead the Southern Jew to fight so fervently for the principle of slavery? Why was he willing to sacrifice his life so readily for a cause that he knew was contrary to religious principle? In their former European lands of oppression Jews actually sought to avoid conscription by any means; yet here in the South they fought willingly and with zest.”

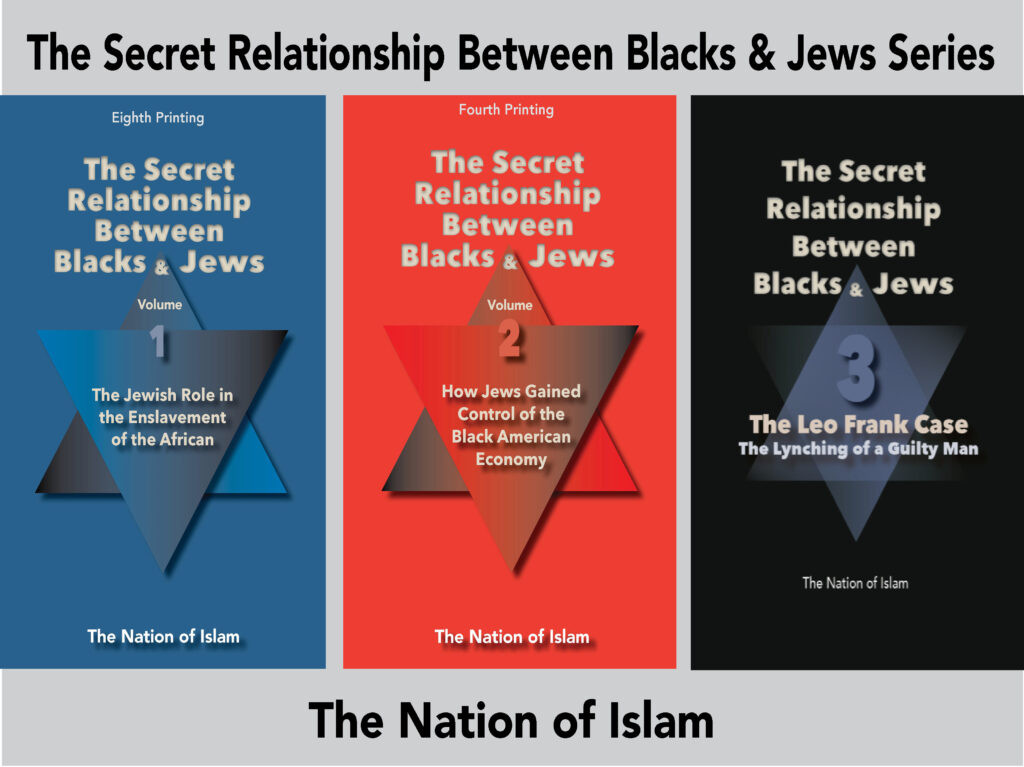

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.