The Slave-Trading Ghosts of Boston’s Biggest Tourist Trap

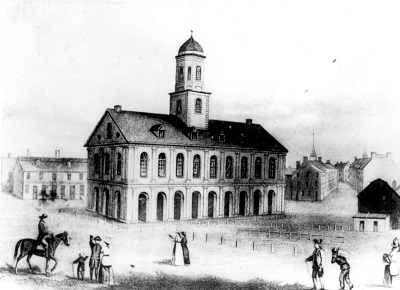

In 1742 Peter Faneuil was Boston’s wealthiest merchant, and built Faneuil Hall as a gift to the city. It is where colonists first protested the Sugar Act in 1764 and established the doctrine of “no taxation without representation.” Great orators such as Oliver Wendall Holmes and Susan B. Anthony spoke there for the abolitionist cause, giving it the nickname “The Cradle of Liberty.” But Cradle of Slavery is a more apt moniker.

Peter Faneuil was typical of the many Bostonians who possessed comfortable fortunes amassed from the profits of the slave traffic.[1] He was a slave dealer and inherited his uncle’s elite post as one of the richest men in Boston. In 1708 Peter’s father, Benjamin, committed a common sleight of hand—namely, “emancipation,” designed more to ease a slaveholder’s guilt than to free his enslaved Africans. He emancipated a “Nero”—but only on the condition that he serve Faneuil and his heirs for ten years! On June 16, 1718, Peter’s uncle Andrew Faneuil was selling Black human beings to other whites, from his home. In January 1707, an advertisement appeared in a Boston newspaper that read in part:

Ran Away…A short thick Indian girl, named Grace, aged about 17 years, her face is full of pock holes, very few hairs on her eye-brows, a very flat nose, and a broad mouth….Whoever shall apprehend and take up the said servant and deliver her unto Mr. Andrew Faneuil merchant in Boston….[shall be rewarded].[2]

Peter Faneuil ordered that the proceeds of a fish shipment to the West Indies be used in the forcible purchase of a child, using the language of today’s internet child predators or pedophilic Catholic priests:

for the use of my house, as likely a straight limbed negro lad as possibly you can, about the age of from 12 to 15 years; and if to be done, one that has had the small pox, who being for my own service, I must request the favor you would let him be one of as tractable a disposition as you can find, which I leave to your prudent care and management; desiring, after you have purchased him, you would send him to me by the first good opportunity, recommending him to a particular care from the captain.[3]

Peter’s most famous slave-making expedition was with his slave ship that bore his nickname Jolly Bachelor (an unsubtle allusion to his sexual orientation). The ship was attacked by Blacks and Portuguese in 1742; the captain and crew were killed and the hostages released. Some of the Africans were retaken and the ship was salvaged, with the venture still ending up profitable. Some of the most eminent names of high society were among the purchasers of Faneuil’s kidnapped Africans.

The estate of Peter Faneuil, who died in 1743, included five Black Africans worth from £110 to £150 each.

[1] Lorenzo J. Greene, “Slave-Holding New England and Its Awakening,” Journal of Negro History 13, no. 4 (October 1928): 496; Joyce D. Goodfriend, Before the Melting Pot: Society and Culture in Colonial New York City, 1664-1730 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 116.

[2] The Boston News-Letter, January 27, 1707.

[3] Justin Winsor, The Memorial History of Boston, 1630-1880, vol. 2 (Boston, 1886), 262-63; James Pope-Hennessy, Sins of the Fathers: A Study of the Atlantic Slave Traders, 1441-1807 (New York: Knopf, 1968), 230. It was believed that once a person contracted smallpox and survived, he was from then on immune from the disease.

[4] Lorenzo Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York, 1942), 28-29; Elizabeth Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America (Washington, DC, 1935), 4:52-65; John Jennings, Boston: Cradle of Liberty (New York: Doubleday, 1947), 89-90; Lilian Brandt, “The Massachusetts Slave Trade,” New England Magazine, n.s., 1 (1899), 89-90; Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 42.