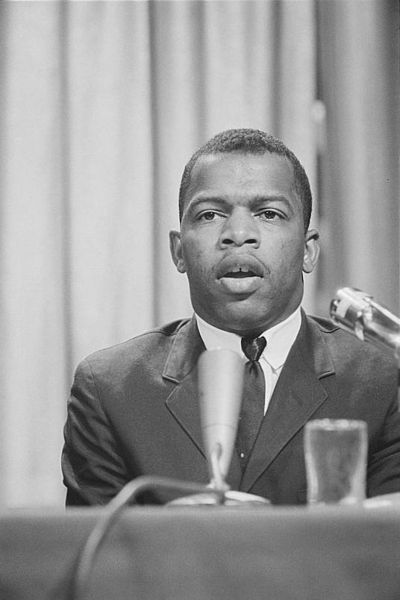

The John Lewis You Never Knew

At one time, John Lewis exhibited a penchant for an aggressive Black activism within the civil rights movement. The “nonviolent” John Lewis once described the organization he once led (SNCC) as an organization of students who were “part domestic Peace Corps and part guerrilla warfare.” He once admitted that “[m]ore and more blacks…including myself, took the position that the black movement…had to be black-controlled, black-led, and black-dominated….The young Turks [militants] had come to feel old-line Negro groups like the NAACP and the Urban League were too bound up with white people, too close to their white money supply to have the necessary maneuverability—especially on the ballooning question of the war in Vietnam.”

Mounted on the wall of SNCC’s Atlanta office was a poster that read “NO VIETNAMESE EVER CALLED ME NIGGER.” Lewis mocked “middle-class Negroes and whites who engaged in a ‘tea and cookie’ approach to the issues: The white people drink all the tea, and the Negroes eat all the cookies.” Of integration, he uttered heretically:

“Too many of us are too busy telling white people that we are now ready to be integrated into their society…I am convinced that this country is a racist country. The majority of the population is white, and most whites still hold a master-slave mentality.

When Lewis was to be a featured speaker at the “I Have a Dream” March on Washington in 1963, the first draft of his speech warned whites that Blacks would

“take matters into our own hands and create a source of power outside of any national structure….Patience is a dirty and nasty word.…We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own “scorched earth” policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently.”

When a white clergyman threatened to pull out of the march if the speech was not toned down, Lewis expunged the offending Black language and replacing it with the inoffensive:

“we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces, and put them back together in the image of God and Democracy.”

Lewis the firebrand soon cooled his passion, opting for the ballot, and in so doing proved, if nothing else, that the quickest way to negro powerlessness and personal obscurity is American elective office. And the difference between the old John Lewis and the new is striking. As SNCC chairman, Lewis had returned from a trip to Africa speaking of revolution:

“I am convinced more than ever before that the social, economic, and political destiny of the black people of America is inseparable from that of our black brothers of Africa. It matters not whether it is in Angola, Mozambique, Southwest Africa, or Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Harlem, U.S.A. The struggle is one in the same. It is a struggle against a vicious and evil system that is controlled and kept in order for and by a few white men throughout the world.”

When Congressman Lewis was asked what his role should be in ending South African apartheid, he sounded quite a bit less aggressive: “I do think we have an obligation, but what can you do from so many thousands of miles away?” His domestic agenda is just as befuddled and non-specific, centering around the establishment of something he calls a “beloved community”—his favorite phrase. By most accounts, Lewis has forfeited a racial justice agenda to be a ceremonial, “moral” negro presence on the House floor.

The old John Lewis quite likely would have been overjoyed to participate in the Million Man March in 1995. Of the Black Muslims (who sponsored the March) he once said, “SNCC, for instance, could well use some of the disciplines of the Muslims. It would work wonders in our organization.” To no one’s surprise or concern, the new, improved Lewis “condemned” the March, then solicited the white press to film him as he sat in his office with his back to the two million Black men gathered outside his window. Lewis wanted his white Georgia constituency to see him dutifully opposed to his Black brothers in the field. In fact, in 1986 Lewis got only 40 percent of the Black vote but 80 percent of the white vote—in a district that is only 40 percent white. Of this new racial orientation, former Martin Luther King aide Hosea Williams “grumbled” that Lewis “used to be a grassroots leader.” The New Republic magazine, acknowledging that Lewis’s message holds no appeal for the Black masses, aptly labeled him “The Last Integrationist.”

Now he says Trump is “illegitimate”?

See 7 Shocking Quotes from Martin Luther King

Order the new, updated, and expanded book, HOW WHITE FOLKS GOT SO RICH: The Untold Story of American White Supremacy: https://noirg.org/store/