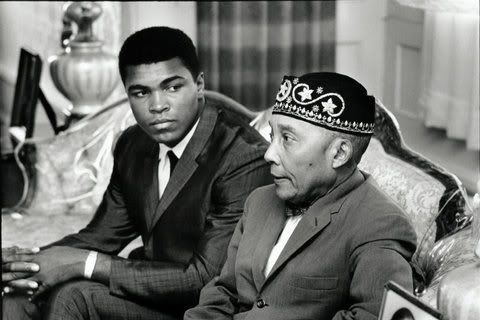

Muhammad Ali’s Beloved Teacher, The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad

Demetric Muhammad

I join the entire world of admirers, supporters, and fans of the greatest boxer that ever lived, Muhammad Ali, in expressing my condolences to his family and in declaring my sense of loss and mourning upon learning of his passing.

Ali’s accomplishments in and out of the ring are legendary. He was a magnificent and talented pugilist who changed the sport of boxing forever. He is rightly credited with paving the way for the large purses that many top-tier fighters earn today. And he broadened the appeal of boxing, making it a universally popular sport as a result of his unusual confidence, media magnetism, and unimaginable ability as a knockout artist.

Many writers, commentators, and analysts are expressing themselves in articles or on-air appearances devoted to the remembrance of Muhammad Ali, but so far I have not found any that speak for me. So I must speak for myself.

I never met the great champion, but I feel a connection to him because many years before me, Muhammad Ali became a student of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad’s teachings and a member of the Nation of Islam. And like myself, he served as a member of the Nation of Islam’s male class known as the Fruit of Islam and as a student minister in the Nation of Islam representing the teachings to mosques and public audiences throughout the country.

He grew up in Kentucky. I grew up also in the South in Mississippi. In the magnificent documentary devoted to his life and struggle against the U.S. government’s conscription of men for the war in Vietnam, I learned more about his life growing up in Louisville, Kentucky. One aspect that grabbed my attention is the segment that talks about his mother’s objection to him becoming a Muslim. I also experienced the same consternation and objection of my joining the Nation of Islam at 15 years of age by my mother, who had been rearing me in the Baptist church.

So, despite never having an in-person interaction with a man that I consider my “big brother” in Islam, I feel a sense of closeness to him. I feel connected to him. And I feel a sense of personal loss knowing that his physical presence is no longer in the world. Yet, his beautiful children carry their father’s physical likeness in such a wonderful way that to see them is to really see him over and over again.

Again, I have not heard any commentators speak for me. By that I mean that none have either expressed what I feel or shown forth an analysis that harmonizes with what I think is important to highlight at this time. The closest were the strong words of historian Zaheer Ali on MSNBC. I also enjoyed and agreed with much of what Maxwell Strachan wrote in his Huffington Post article “Don’t Let Muhammad Ali’s Story Get Whitewashed.”

So that only means that I have to speak for myself and in so doing, speak for the many others who feel as I feel. Specifically obvious to those of us who share Ali’s faith in Islam is the crafty strategy to portray him as an enigma and exception to the rest of Muslims. For sure, the talent that Allah (God) blessed him with from birth was and is exceptional. Yet raw talent and raw materials of any kind remain “in the raw” and remain uncultivated unless there is someone to develop them and extract them from a raw state so that their beauty and value may be known. Such is the case with human beings. So much so that it has been suggested that the greatest travesty in the world today is the enormous waste of human potential.

In Muhammad Ali’s rise as an athlete and as a trailblazer of the athlete-activist archetype, there is one man that is conspicuously absent from all recent conversations. That man is largely responsible for the cultivation and development of the man who went from being Cassius Marcellus Clay to Muhammad Ali. That man that is routinely hidden and omitted from conversations about Black history and achievement, as if he never existed, is the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad.

So just who is the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad? Let’s take a look at some descriptions of him from some of the most prominent and well-respected persons in history:

Elijah Muhammad has been able to do what generations of welfare workers and committees and resolutions and reports and housing projects and playgrounds have failed to do: to heal and redeem drunkards and junkies, to convert people who have come out of prison and to keep them out, to make men chaste and women virtuous, and to invest both the male and the female with a pride and a serenity that hang about them like an unfailing light. He has done all these things, which our Christian church has spectacularly failed to do.

—James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

“We told our people, ‘It’s got to be done like the Muslims do it. It’s got to be done person to person.’ Of all the movements we know of, we have a lot of respect for you, because you have a lot of people doing things,” he said, referring to the constructive program of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad and its effect on his energetic followers.

—Caesar Chavez, Mexican Farm Worker Leader

Approximately 30 percent of the United States’ six to eight million Muslims are African American, making Islam the second most popular religion among African Americans. Although the vast majority of these African American Muslims are now Sunni Muslims, many (or perhaps their parents or grandparents) were introduced to Islam through the Nation of Islam, a movement that was exclusively Black, segregationist, and militant. Its leader for over forty years, Elijah Muhammad, was therefore arguably the most important person in the development of Islam in America, eclipsing other prominent figures such as Noble Drew Ali, Wali Fard Muhammad, Malcolm X, Louis Farrakhan, and Warith Deen Mohammed (originally known as Wallace D. Muhammad). Despite his unrivaled prominence, Elijah Muhammad is rarely treated as a major figure in Islam.

—Professor Herbert Berg, Elijah Muhammad and Islam

“What the Negro needs first is $100 million,” world famous composer Duke Ellington said last week in an exclusive interview with Muhammad Speaks. “And that is the advantage your boss (referring to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad) has over the rest of the 20 million. He urges that we get some money together.” “Without $100 million there is no voice. There are 20 million Negroes and we don’t have $20 million. MONEY TALKS in our society and economics is the big question throughout the world. Every race on this earth has some money but the American Negro…” This then is the solution to the “race problem” of the famous Duke, who is universally acclaimed as royalty in the realm of American music.

—Duke Ellington interview with Muhammad Speaks newspaper

“We’re here in honor of a man to be respected. In honor of a man who is very much deserved of the praises given to Him for His many deeds that most of us know very little about. I’m here, joining the others to give respect to a very beautiful man that I’ve seen do a lot with my brothers, people who I lived with; as a matter of fact – people that I am. He has most definitely been a positive influence…I’ve got to respect this man for His works.”

—Curtis Mayfield, on the Occasion of Elijah Muhammad Appreciation Banquet, 1974

DEAR MR. MUHAMMAD,

An engagement of long standing in Madison, Wisconsin prevents my accepting your invitation to attend your testimonial dinner on March 29th. I do, however, want to extend my personal best wishes to you and my congratulations on your almost half a century of productive leadership.

—Vernon E. Jordan Jr., Director, National Urban League, 1974

These Black Muslim women looked at the Nation, and saw love and courage. To them the Honorable Elijah Muhammad was a man who loved his people so much that he designed an institution in which the primacy of women was integral, and every man in the organization was obligated to put himself on the line for them. Black Muslim women saw this as a measure of love and respect for them.

—Cynthia S’thembile West, scholar and author of Nation Builders: Female Activism in the Nation of Islam, 1960–1970

I, as many of you, sat at the feet of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and shared and was taught. The Messenger made the message very clear. He turned alienation into emancipation. He concentrated on taking the slums out of the people and then the people out of the slums. He took dope out of veins and put hope in our brains. He was the father of Black consciousness. During our “colored” and “Negro” days he was Black. His leadership exceeded far beyond the membership of the Black Muslims. For more than three decades, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad has been the spiritual leader of the Black Muslims and a progressive force for Black identity and consciousness, self-determination and economic development.

—Rev. Jesse Jackson, Rainbow PUSH

Without question, he [Hon. Elijah Muhammad] aided many young Black Americans to gain dignity and hope and a will to survive. I have a great deal of admiration for the sense of discipline he provided for many young Black men and women.

—John Lewis, U.S. congressman, former head of SNCC

Elijah Muhammad gave Blacks new confidence in their potential to become creative and self-sufficient people. In addition, he taught his followers the efficacy and rewards of hard work, fair play, and abstinence. It has been shown beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Muslims who have followed his economic teachings have been comparatively prosperous and have in many cases moved substantially ahead in their economic pursuits. He gave also his people a success formula for home and family life. The rate of delinquency among Muslim children is extremely low. The rate of divorce is quite low. The stability of the Muslim home is an ideal for which the rest of America might strive.

—Dr. C. Eric Lincoln, author of Black Muslims in America

Mr. Muhammad’s life was one of peace, harmony, and great integrity. He made the Nation of Islam a pillar of strength in Black communities throughout the country.

—Ralph Metcalfe, former U. S. representative, 1st District, Illinois, and a co-founder of the Congressional Black Caucus

I tell people again and again and again that I know what I know not because of anything U.C. Berkeley [University of California Berkeley] taught me, but because I learned what I learned in the Nation of Islam. I learned it from the sisters, who learned it, basically, from Elijah Muhammad—and it worked! It changed a people who, just like my Indian people, had a terrible diet. Still a lot of work needs to be done in the African American community, but Elijah Muhammad was successful in alerting, millions probably, of African American people about pork and leading a healthier life.

—Diane Williams, MPH, Native American social worker

“Whiting H & G,” “Hereafter,” and “Fruitman” (songs from their album Light of Worlds) are meant to reflect a message of unity and seriousness from the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.

—Robert 9X Bell, founding member of Kool & The Gang

The Hereafter means Freedom, Justice and Equality and I never knew anything about that until I started following the Messenger. When we first accepted Islam in Jersey City, N.J., the rest of the band was against it. They even tried everything to stop us from coming in. But now Islam is attracting them.

—Ronald 6X Bell, founding member of Kool & The Gang

Once I heard the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad; that really touched me. It was something I could relate to and made me do better. Once you have heard the teachings (of the Nation of Islam) and know the knowledge, there is no turning back.

—Larry Johnson, NBA basketball star

I could go on and on. But this is just a small introduction to the magnificent man who is at the root of the great boxing champion and activist Muhammad Ali. Ali loved the most Honorable Elijah Muhammad for what he did for him in his life and trajectory that propelled him onto the world stage.

Now if that list does not drive home the importance of the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad on the life and success of Muhammad Ali, let’s consider some of Ali’s own glowing words about his beloved teacher.

From Thomas Hauser’s book Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times:

The first time I heard about Elijah Muhammad was at a Golden Gloves Tournament in Chicago [in 1959]. Then, before I went to the Olympics, I looked at a copy of the Nation of Islam newspaper, Muhammad Speaks. I didn’t pay much attention to it, but lots of things were working on my mind. When I was growing up, a colored boy named Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi for whistling at a white woman. Emmett Till was the same age as me, and even though they caught the men who did it, nothing happened to them. Things like that went on all the time. And in my own life, there were places I couldn’t go, places I couldn’t eat. I won a gold medal representing the United States at the Olympic Games, and when I came home to Louisville, I still got treated like a nigger. There were restaurants I couldn’t get served in. Some people kept calling me “boy.” Then in Miami [in 1961], I was training for a fight, and met a follower of Elijah Muhammad named Captain Sam [Minister Abdul Rahman Muhammad]. He invited me to a meeting, and after that, my life changed.

In a November 1975 Playboy magazine interview the champ stated:

He was my Jesus, and I had love for both the man and what he represented. Like Jesus Christ and all of God’s prophets, he represented all good things…. Elijah Muhammad was my savior, and everything I have came from him—my thoughts, my efforts to help my people, how I eat, how I talk, my name.

Muhammad Ali went on to discuss how he would like to be remembered:

I’ll tell you how I’d like to be remembered: as a Black man who won the heavyweight title and who was humorous and who treated everyone right. As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him and who helped as many of his people as he could—financially and also in their fight for freedom, justice and equality. As a man who wouldn’t hurt his people’s dignity by doing anything that would embarrass them. As a man who tried to unite his people through the faith of Islam that he found when he listened to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. And if all that’s asking too much, then I guess I’d settle for being remembered only as a great boxing champion who became a preacher and a champion of his people. And I wouldn’t even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.

In the excellent documentary The Trials of Muhammad Ali, there is a section where his love for orange juice is discussed. And Ali is certainly not alone in loving orange juice. And it only makes sense to me that if one love’s orange juice, one must love the orange that produced the sweet vitamin-rich juice. And it logically follows that if one loves oranges, one must love the orange tree that produced the oranges that produced the golden pulp-filled nutritious orange juice. Perhaps this kind of logic should be applied in the case of Muhammad Ali and his beloved teacher the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad. Because it is not logical to love the student and hate the teacher that produced the student.

Demetric Muhammad is a student minister in the Nation of Islam and a member of the Nation of Islam Research Group. Follow him on Twitter @brotherdemetric and read more from him at www.researchminister.com.