Cruel Jewish Plantation Masters: Mordecai Cohen & Son

“Slaves of Charleston,” The Jewish Daily Forward, September 15, 2014

The Beth Elohim Synagogue, founded in the 1749 in downtown Charleston South Carolina, is one of the very earliest synagogues in America. While other more recent synagogues and congregations are also now a part of Charleston city life, as the oldest one in the area, the Beth Elohim Synagogue is the repository for certain historical artifacts of Jewish life in the city. One such artifact they hold is a marble tablet honoring Mordecai Cohen (1763-1848) that was commissioned by the City of Charleston to honor one of the city’s greatest benefactors. Cohen, one of the wealthiest men in South Carolina, had long supported and donated money to the Charleston Orphan’s House – the first public orphanage in the United States and one that relied upon both public funds and private patrons to serve the white poor of the city of all faiths. Mordecai Cohen served as a commissioner to the Orphan’s House for ten years and made hefty contributions for forty-five years.

The Jewish community of Charleston has long been civically engaged, seeing the health of their own families and communities intrinsically linked to the health and good will of the city at large. Early Jewish immigrants to Charleston were attracted in part because of its tolerant reputation towards those of different faiths but also for its location as the nearest major port city to colonies of the West Indies. While some arrived from New York or Rhode Island, others arrived from Barbados, Jamaica and other British settlements in the Caribbean. The first wave of immigrants were largely of Sephardic descent but were followed in the mid 18th century by more German speakers and people of Ashkenazi heritage.

One important population influx was in 1741 when a large contingent of Jewish families left their homes in Savannah, Georgia to resettle in Charleston because trustees of the Georgia colony would not let them (or anyone else) hold slaves. The state of South Carolina, which had long embraced slaving, was thus a welcoming place for these ambitious families. By 1749 when Georgia rethought the ban and decided to allow slaveholding, it was too late. Some families, of all faiths, moved back but many remained and Charleston decisively eclipsed Savannah as the center for Southern Jewish settlement. By 1800 South Carolina, (and this really meant Charleston and its environs) held the largest Jewish population of any state. Estimates put some 500 Jewish people in Charleston at that time when there were probably only 400 in New York and perhaps 2, 500 in the newly established United States.

So what did it mean to be a Jewish citizen of Charleston during the early years of the 19th century? We can look Mordecai Cohen to understand a small part of the privilege and the price of being a leading Jewish citizen of Charleston.

… … …

Cohen, born in Poland in 1763 began work as a young immigrant peddler in Charleston but rapidly rose in status and wealth. Eventually he owned many properties across the city and large estates on the nearby Ashley River. Revered as a philanthropist who especially supported the Charleston Orphan House, Cohen was a central figure not merely in the Jewish community of South Carolina, but in the nation – embodying a new vision of what American citizenship and success might look like.

Cohen, born in Poland in 1763 began work as a young immigrant peddler in Charleston but rapidly rose in status and wealth. Eventually he owned many properties across the city and large estates on the nearby Ashley River. Revered as a philanthropist who especially supported the Charleston Orphan House, Cohen was a central figure not merely in the Jewish community of South Carolina, but in the nation – embodying a new vision of what American citizenship and success might look like.

The price for Cohen’s success was his willing participation in the slave trade. While he never held the hundreds of field hands that other low country Carolina plantations of that time boasted, he owned enough people to maintain his properties and to keep his family comfortable. This wasn’t surprising: the percentage of Jewish Charlestonians who held slaves in1830 (83%) was roughly the same as in the general white population of that city (87%). In addition to his extensive mercantile and real estate endeavors, he was deeply involved in the slave trade—the auctioning, mortgaging and leasing of babies, parents, and families. Orphans of color evidently were of no special interest to him.

Cohen set up his own sons on nearby plantations that rivaled some of the greatest in the South. Indeed, it was right around Lafayette’s visit in 1824 that Mordecai Cohen bought Soldier’s Retreat, a large estate of over 1,000 acres overlooking the Ashley River for his son David. By the 1830s David or “Davy” Cohen had taken over the estate in his own name and held slaves who worked his fields, emptied his slops, and raised his children.

All of this makes the Cohen family story little different from any other story of successful southern capitalists of the time. But little-known testimony from someone who was enslaved by the Cohens does exist and his perspective allows us to see Mordecai and his son David for the cruel people that they were.

One of these slaves was a young man named Jim, who was not impressed by the Cohen wealth. Jim escaped from slavery and narrated the story of his life to northern Abolitionists in one of the earliest abolitionist American slave narratives, Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave (1838) – a graphic account of torture and suffering. In his memoir Jim paid careful attention to his experiences under the Cohen family providing details that would help authenticate his own story and also indict the horror of the slave system more broadly.

Jim worked as a hostler or a groom for David Cohen but also did field work. He described David Cohen as a man of relentless vigilance. “He was in the habit of walking about at all hours of the night to find out who stole wood, or turnips, or hogs, or any thing else.” When he suspected anyone of thieving the punishments were dire. One old man, Peter, was found stealing a few sticks of wood from David Cohen. Jim testified that Peter was whipped for hours until he was unconscious and then doused with brine before being chained in the stocks kept on the plantation for just such occasions.

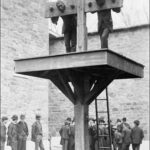

After being on the receiving end of one especially cruel whipping by David Cohen’s overseer, Jim fled Soldier’s Retreat and hid with a community of black fugitives in the dense swamps. Recaptured after only few brief weeks of freedom, Jim was brutally punished with another whipping. When sympathetic interviewers later transcribed his story they added a footnote testifying that the fugitive’s scars all over his body “appear as if pieces of flesh had been gouged out, and some are ridges or elevations of the flesh and skin. They could easily be felt through his clothing.”

Uncowed, however, he soon fled again, this time seeking out his sister at a nearby plantation. She told him that David Cohen had reportedly offered a $50 reward for his capture. Before she or Jim could contrive a plan for his safety, he was once again spotted and captured. This time, though, he wasn’t returned to Cohen’s Ashley River estate. He was instead taken to the Sugar House, a notorious workhouse jail in Charleston especially famous for its treadmill run by slave labor that not infrequently maimed and killed the weary people chained to its rotating pedals, as well as for other punishments so unsavory that genteel enslavers preferred them to be done out of sight. Jim described the whippings and torture being carried on continuously at all hours of the days and nights, such was the demand for the Sugar House services: “You may hear the whip and paddle there, all hours in the day. There’s no stopping.” He added: “I have heard a great deal said about hell, and wicked places, but I don’t think there is any worse hell than that sugar house.”

At the Sugar House, Mordecai Cohen was informed of Jim’s plight and after assessing the situation, sent for his son. David Cohen came in from his estate and stopped by the Sugar House. As Jim remembered it, “He told them to whip me twice a week till they had given me two hundred lashes. My back, when they went to whip me, would be full of scabs, and they whipped them off till I bled so that my clothes were all wet.” The guards were instructed to alternate bouts of whippings with days on the treadmill for several weeks.

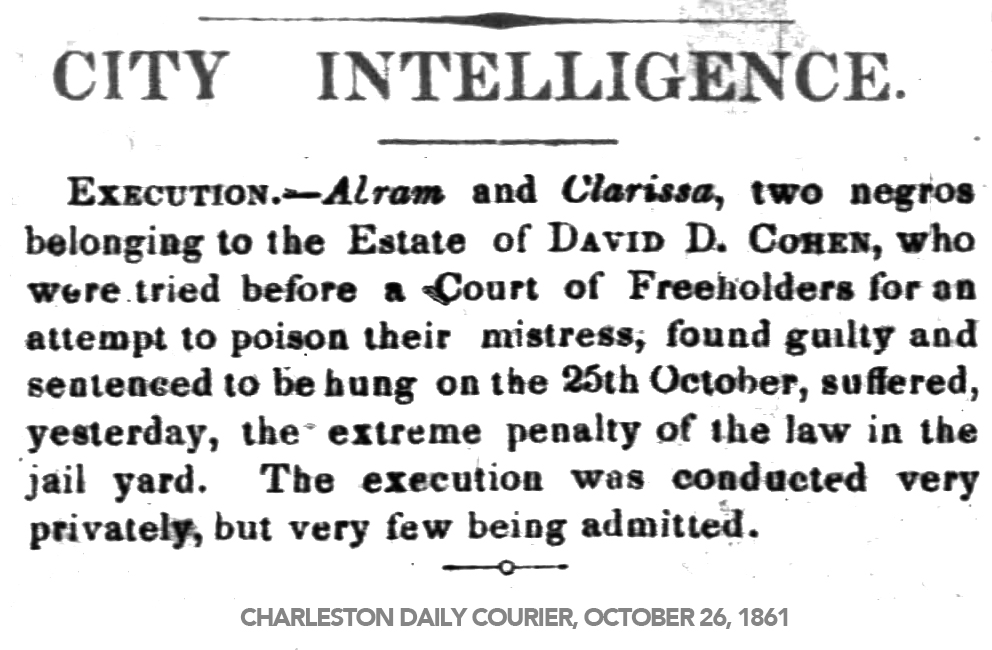

David Cohen visited Jim in the Sugar House and determined that he was an unrepentant runaway who, no surprise, was rapidly losing value under the continual torture. Finally, after several attempts to sell him, in June of 1837 David Cohen received $700 dollars from a speculator for young Jim. When your life price is bartered, you don’t forget the obscenity of the transaction and Jim was later able to find some satisfaction from the fact that David Cohen had sold him at a dramatic loss from his original purchase price.

Jim’s story moved in dramatic fits and starts from there. He was hired out to a railroad, escaped once again and this time made it aboard a Boston–bound boat. He was harbored by abolitionists in Maine who recognized the publicity value a story such as his would have for their cause and transcribed his story for the public. Although published anonymously, a runaway slave advertisement from the Charleston Courier of December 11th 1837 clearly identifies Jim as the fugitive who had been owned by Cohen and who never forgot his encounters with that family. It reads: “Fifty Dollar Reward. Runaway from the Subscriber, a few weeks ago, his fellow JIM, lately purchased from Mr. David D. Cohen, of Charleston.”

The Cohen family was similar to thousands of other slave owners during that era but that doesn’t mean that their story, in its specifics, doesn’t need to be seen for all of its pain. They weren’t just “slavers” in a vague sense. They owned and tortured Jim, a man who remembered them clearly and survived to serve witness to such horror.

David Cohen’s plantation on the Ashley River was demolished but at least one of the grand mansions of Mordecai Cohen still stands at 119 Broad Street and functions as offices for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston. Today, a handsome portrait of Mordecai Cohen is held by the Gibbs Museum of Art in Charleston and testifies to the critical presence of Jews in Charleston history. The Cohen family philanthropy was very real; it helped rescue and nurture generations of Jewish and Christian orphans. But so too was the reality of the Cohen family indifference to the lives of the people they owned. The gold plates Mordecai Cohen was able to lend out to honor the Marquis had been obtained at a terrible cost.

[Susanna Ashton is a Professor of English at Clemson University in South Carolina and regularly writes about the lives of enslaved people.]

^^

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.