A Black Viewer’s Guide to Spielberg’s Lincoln

“I agree that he is not my equal in many respects, certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment.” —Abraham Lincoln

by NOI Research Group

Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln opened last week, and many have flocked to see this Hollywood version of one of the nation’s most tumultuous times—the American Civil War. The film purports to recount the last months of the life of Abraham Lincoln as he lobbied to achieve the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which is said to have ended legal slavery in America—at least on paper.

Spielberg is the master of American propaganda, and there is no one since the notorious director D.W. Griffith who has more successfully exported to the world a utopian vision of America as a Caucasian paradise. And while his white characters—from Jaws to ET to Amistad—show a range of virtues, his Black characters have been limited to cardboard portrayals of simplistic and racially clichéd stereotypes.

This is the inescapable context with which one must approach Spielberg’s Lincoln, a film that is no more accurate in its depiction of a critical period in history than George Bush was about the so-called weapons-of-mass-destruction lie that brought a world of nations to endless war.

First, let us take a couple of paragraphs to dispose of some well-entrenched historical myths. No war in the 6,600-year history of the white man has ever been fought for the benefit of Blacks—never has happened and never will. If the North fought to “free the slaves,” then why did the war start with the slaveholding South attacking the Union at Fort Sumter? Should it not have been the reverse? The Civil War was fought between two sets of white people to see which one would benefit most from the multitude of products America derived from Black slave labor. Southerners realized that the engines of the American economy—cotton and slaves—were in their territory.

They resented that the big banks in the North were making most of the profits from their plantations. They decided to end that one-sided relationship and SEPARATE from America. Abraham Lincoln knew that America would collapse without Southern slavery and reluctantly fought the war to maintain the UNION of North and South—and, most important, to keep the slavery wealth flowing from South to North.

No one fought to free Black people, and, indeed, before a single shot was fired both sides agreed to the Crittenden Resolution, which made it clear that the war would not target what they called “established institutions,” namely, Black slavery. Here are a few more points: While still engaged in the war, Union General Benjamin F. Butler placed his troops at the disposal of the governor of Maryland to repress a rumored slave insurrection. A few more points:

• In 1861, when General John C. Fremont freed all slaves in the state of Missouri, Lincoln fired him. When General David Hunter freed the slaves in three states, Lincoln cancelled and reversed the order.

• Union military camps were closed to runaway slaves, and some poor Black souls were actually captured by Union soldiers and returned to their rebel owners!

• Most abolitionists were white workers who HATED Blacks but wanted an end to slavery so that they—whites—would not have to compete with Black workers.

• Lincoln had no intention of establishing “integration” and in 1862 sent 450 “freed” slaves to an island off the coast of Haiti in an ill-fated colonization scheme. The navy had to be sent to retrieve the beleaguered Blacks.

• Lincoln publicly voiced support for the Fugitive Slave Law, which made every American citizen—North and South—responsible for catching runaway slaves.

• While still engaged in the war, Union General Benjamin F. Butler placed his troops at the disposal of the governor of Maryland to repress a rumored slave insurrection.

• In 1861, when General John C. Fremont freed all slaves in the state of Missouri, Lincoln fired him. When General David Hunter freed the slaves in three states, Lincoln cancelled and reversed the order.

• Union military camps were closed to runaway slaves, and some poor Black souls were actually captured by Union soldiers and returned to their rebel owners!

• Most abolitionists were white workers who HATED Blacks but wanted an end to slavery so that they—whites—would not have to compete with Black workers.

• Lincoln had no intention of establishing “integration” and in 1862 sent 450 “freed” slaves to an island off the coast of Haiti in an ill-fated colonization scheme. The navy had to be sent to retrieve the beleaguered Blacks.

• Lincoln publicly voiced support for the Fugitive Slave Law, which made every American citizen—North and South—responsible for catching runaway slaves.

Contrary to popular belief, Lincoln’s famous Emancipation Proclamation did not “free” a single Black person from chattel slavery—not one. When it looked like the Union was losing the war, Lincoln “freed” slaves in the South so that they could fight against their masters. In that same document he made sure that slavery was not disturbed where it existed in the North!

These are hardly the acts of a Saviour or of a Salvation Army. But they are truths that dirty the image of Lincoln, whom Spielberg is posing as America’s very own Christ figure—the man who died for the racial sins of a nation.

Spielberg is intent on hiding these important facts, portraying his subject as the avuncular oracle of racial kindness. But Spielberg is not so charitable with the Black characters that appear throughout his wartime fairytale. It opens with a combat scene, but the first death we see is a Black man stabbed in the chest with a bayonet—Spielberg preserves an honored Hollywood tradition that Blacks must be the first to die.

President Lincoln is then shown in the midst of a Union camp earnestly listening to the battlefield accounts of two Black soldiers. Spielberg puts them with the Second Kansas Colored Regiment, an actual Black military unit, though their encounter with the President is totally fictional. What is troubling is that one of the soldiers describes a combat event in which, he says, his colored unit “killed them all”—every last one of them. This is a description of a war atrocity—not a battle in which the enemy was beaten badly—and it is Spielberg’s way of making the Black race responsible for the extreme brutality of America’s deadliest war (750,000 dead). The Jenkins Ferry battle was indeed brutal and bloody, but if an order were given to “kill them all” it would have had to come from the white leader of the “colored” unit.

Spielberg’s other Black soldier presses the President for equality in an unrealistically brash dialogue that would have earned him time in a dungeon after many lashes. Yet Spielberg’s brazen negro has the temerity to ask Lincoln for a job! This again is a bold falsehood that misstates the actual condition of the Black race. Blacks were not asking for jobs—because during slavery and for a time after the war they dominated all of the skilled crafts in the South and were capable builders, inventors, and independent-minded believers in their own talents and skills. The fact is, whites feared that freeing Blacks would leave whites totally stranded and uncared for. In many cases, the Black slave of a white family was the only breadwinner in that family! If America were to actually allow the ex-slave 40 acres, a mule, and the vote, whites would be homeless, friendless and hopeless in a matter of days.

From there, Spielberg gives us Black caricatures direct from the set of Gone With The Wind. We see Mrs. Lincoln’s mulatto maid, Mr. Lincoln’s dutiful butler, the trusty carriage driver, the obligatory Blacks praising God for the white man’s largesse, and the Lincolns’ child oddly playing with slavery photos like they are baseball cards. Jewish writer Tony Kushner puts “nigger” in the mouths of too many whiteys, but not in the mouth of Lincoln, who actually used the word with chilling regularity.

And then there is the last scene, when Thaddeus Stevens, played by Tommy Lee Jones, grabs the original copy of the 13th Amendment and brings it home, where he is greeted by his Black housekeeper Lydia Smith, played by S. Epatha Merkerson. He presents it to her with the words “a gift for you,” whereupon the satisfied servant crawls into bed with the white man, for a night of emancipation fornication, one assumes.

Centuries of slavery meant the daily debasement and brutal rape of the Black woman (see Legitimate Rape: A Truly American History). In his nauseating reconstruction Spielberg shows us what he feels are the “benefits” of the legal end of slavery—even more of the white man’s sexual debasement of the Black woman!

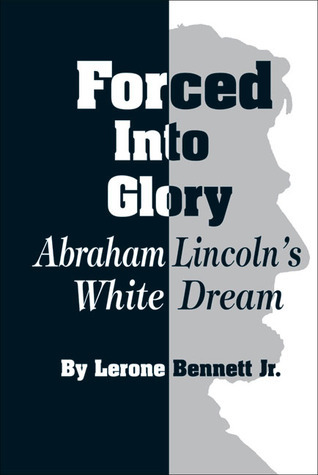

In reality, Abraham Lincoln is no hero for the Black man. Ebony Magazine editor historian Lerone Bennett wrote a landmark 652-page book titled Forced Into Glory that really ends all debate in the matter. But Hollywood would have to hold its nose in reading the true history of Lincoln’s racial words and deeds. And then there’s the forgotten fate of the Native American, whose Holocaust was accelerated by Lincoln’s murderous expansionist policies, which unleashed violent white settlement on Indian lands in the West.

In analyzing the insufferable idolization of this supreme white supremacist, one is reminded of the words of Elijah Muhammad: “Abraham Lincoln was not instrumental in trying to free you….The truth will make you free.”

A Viewer’s Guide to Spielberg’s Lincoln (Part 2)

by NOI Research Group

In his movie Lincoln, director Steven Spielberg presents a critical period of the Black Holocaust as he feels Blacks ought to understand it. But he is no historian. The Jewish Spielberg has meticulously filmed and archived the stories of Jewish Holocaust survivors for his Shoah Foundation in order to preserve the accuracy of their experiences. So why then is Spielberg so dreadfully senile in his representation of a time so important to Black Americans? Why, for instance, does he feel free to promote a fairy tale of the history of the Civil War and Black slavery, but suspiciously ignores the critical role played by his own Jewish people in the War Between the States, a war in which Jews were extremely prominent and consequential?

This is not an oversight. Spielberg employs top historians and researchers to ensure the accuracy of his product and to ensure that his race is represented with dignity and respect. Lincoln the movie is about the birth of the 13th Amendment, a Constitutional decree that was purported to be the “end of slavery.” But just as with the “All-Men-Are-Created-Equal” part of the Declaration of Independence, the unlucky 13th was simply ignored—and slavery continued unabated in other forms. When hostilities ceased, both sides quickly reconciled and unified to put Blacks back onto plantations in a far more effective economic system than slavery—namely, sharecropping, debt peonage, and convict labor. Readers of the book The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Vol. 2, can attest to the effectiveness of the Talmud-based system that replaced slavery in America. Somebody had to plant, cultivate and pick the cotton, corn, wheat, and sugar, build the railroads and bridges, and load and unload the ships feeding international trade.

Spielberg wants to reinforce the fiction that a single document exonerated America and ended forever a system by which his people grew so wealthy. Take Spielberg’s own Hollywood for example. It is called by Jewish scholar Neal Gabler “An empire of their own”—a reference to the Jewish moguls who ran all the major studios. Hollywood is the product of investment by the notorious banking house Lehman Brothers. At one time in the 1850s the immigrant Mayer Lehman was appointed by the governor to be in charge of ALL the cotton in Alabama—which meant he was in charge of the state’s Black African slaves. His Jewish family generated so much money from slave labor that they adamantly fought against Lincoln’s attempts to end Black slavery. With their cotton-trading profits they moved to New York and got into investment banking, ultimately financing the studio “empires” of Steven Spielberg and his forbears.

Spielberg wants to reinforce the fiction that a single document exonerated America and ended forever a system by which his people grew so wealthy. Take Spielberg’s own Hollywood for example. It is called by Jewish scholar Neal Gabler “An empire of their own”—a reference to the Jewish moguls who ran all the major studios. Hollywood is the product of investment by the notorious banking house Lehman Brothers. At one time in the 1850s the immigrant Mayer Lehman was appointed by the governor to be in charge of ALL the cotton in Alabama—which meant he was in charge of the state’s Black African slaves. His Jewish family generated so much money from slave labor that they adamantly fought against Lincoln’s attempts to end Black slavery. With their cotton-trading profits they moved to New York and got into investment banking, ultimately financing the studio “empires” of Steven Spielberg and his forbears.

Back to the movie: The opening of Spielberg’s Lincoln is a brutal hand-to-hand combat scene in the later stages of the Civil War. But without the investment of a Jewish banker named Emile Erlanger the latter part of the war would never have happened. In March of 1863 (3 months after the Emancipation Proclamation), Erlanger loaned $7 million dollars to the Confederacy (about $125 million in today’s money), without which the South would have been unable to pay or feed or clothe its troops or buy its warships, its weapons and its bullets. They would have had to surrender. Erlanger expected to get low-cost cotton from the South if the rebels were successful at maintaining slavery. It is safe to say that fully half of the 700,000 soldier deaths might have been prevented if the Confederacy had not had the funds to continue the war. Never mind that many Africans would not have continued to be imported as slaves if this bloody period had been cut short. Spielberg ignored those unfortunate Judaic details.

Back to the movie: The opening of Spielberg’s Lincoln is a brutal hand-to-hand combat scene in the later stages of the Civil War. But without the investment of a Jewish banker named Emile Erlanger the latter part of the war would never have happened. In March of 1863 (3 months after the Emancipation Proclamation), Erlanger loaned $7 million dollars to the Confederacy (about $125 million in today’s money), without which the South would have been unable to pay or feed or clothe its troops or buy its warships, its weapons and its bullets. They would have had to surrender. Erlanger expected to get low-cost cotton from the South if the rebels were successful at maintaining slavery. It is safe to say that fully half of the 700,000 soldier deaths might have been prevented if the Confederacy had not had the funds to continue the war. Never mind that many Africans would not have continued to be imported as slaves if this bloody period had been cut short. Spielberg ignored those unfortunate Judaic details.

But there is more: Erlanger made the deal through a Jewish lawyer and slaveowner from Louisiana named Judah P. Benjamin, who was considered the “brains of the Confederacy” and served as its Secretary of War! So significant was Benjamin to the slaveholders that his picture was on their money! Apparently Benjamin failed to pass Spielberg’s audition, because he is not in the movie. Benjamin fled America, taking multiple bales of cotton with him in order to finance his life in exile. After the war, he used his slave-picked cotton profits to invest in a new start-up organization—a terrorist group known as the Ku Klux Klan!

And there is more: Florida senator David Yulee didn’t make the cut either. He was the first Jewish senator in American history—and a vociferous supporter of slavery and an aggressive promoter of Indian “removal.” In 1861, Yulee gave the first speech in the Senate to announce the secession of a Southern state.

Other notables missing from the movie are August Belmont, a Jewish New York banker who was the chairman of the Democratic Party. He was the campaign manager of Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln’s pro-slavery opponent in his last election. Belmont decried abolitionism, denouncing what he called Lincoln’s “fatal policy of confiscation and forcible emancipation.” Another important Jewish American was the highest-paid clergyman in America, the New York-based Rabbi Morris Raphall, who aided and comforted the slaveholders by publicly proclaiming that God Himself supported slavery! When Rabbi David Einhorn said that Blacks should be treated better, he was run out of his Baltimore synagogue in the middle of the night—by his own Jewish congregation!

Then there were those Jewish merchants who smuggled the valuable cotton out of the South even though Lincoln had ordered it blockaded. Their illegal operations gave the South the money it needed to fight for slavery. There were so many of them doing so much damage to the Union cause that General Ulysses S. Grant tried to expel all the Jews from the region! These slavery-supporting Jewish smugglers didn’t make it into Spielberg’s movie either.

Spielberg wants us to believe that Blacks were President Lincoln’s main problem, but Lincoln had lots of trouble with the Jews of his time. An official of Lincoln’s government actually deemed the main Jewish organization, the B’nai B’rith, to be a “disloyal organization” that “help[ed] the traitors.” When Salomon de Rothschild, a member of the biggest banking family in the world, showed up in America, he said that if he were an American he would be a “Staunch Slavery Man,” and he urged his family to help the Confederacy. And though Spielberg presents a grandfatherly Lincoln as an Aesopian storyteller, Rothschild disagreed and denounced him as having “the appearance of a peasant [who] can only tell barroom stories.”

Jewish women were equally disdainful of the President, as scholar Albert Mordell noted: they “were more virulent in their hatred of Lincoln and more fanatical in upholding the Confederacy than the men.” In fact, Jews were so fanatical that another Jewish scholar was moved to ask,

“What sociological phenomena would lead the Southern Jew to fight so fervently for the principle of slavery? Why was he willing to sacrifice his life so readily for a cause that he knew was contrary to religious principle?…[H]ere in the South [Jews] fought willingly and with zest.”

The answer to that question is not in the movie Lincoln, but it is in the Jewish Encyclopedia: “[T]he cotton-plantations in many parts of the South were wholly in the hands of the Jews, and as a consequence slavery found its advocates among them.” Roberta Feurlicht, in her book Fate of the Jews, frankly concluded: “Not only were a disproportionate number of Jews slave owners, slave traders, and slave auctioneers, but when the line was drawn between the races, they were on the white side.”

So it is probably understandable why Steven Spielberg’s movie about the purported end of Black slavery had to be made without Jewish characters. The carefully crafted but totally false image of Jews as helpers of Blacks would surely have been forever jeopardized. Their absence from any participation in Lincoln’s efforts to achieve Black freedom is probably the only historically accurate feature of the film.

And since Spielberg’s 2012 film must still portray Blacks only as servants and maids and butlers and carriage drivers and concubines, maybe Blacks ought to reflect on and consider Lincoln’s most profound proclamation. He said:

“The aspiration of men is to enjoy equality with the best when free, but on this broad continent not a single man of your [Black] race is made the equal of a single man of ours….I cannot alter it if I would….It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated.”

Now, that would make a great movie.

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.