The Growth and Demise of Black Land Grant Institutions

By Dr. Ridgely Abdul Mu’min Muhammad

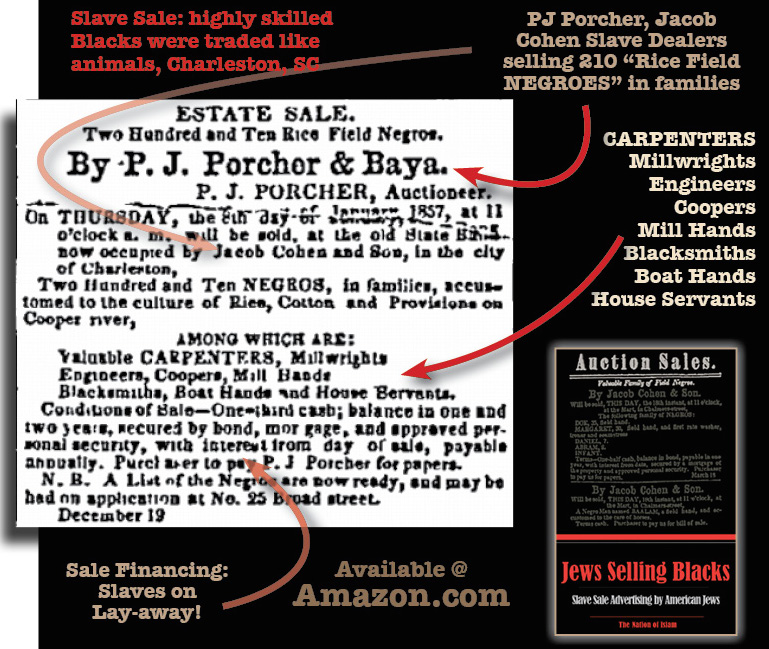

(Final Call, October 17, 2013) In Jews Selling Blacks we learned that many slaves were not just field hands, as an 1857 estate auction sale advertisement shows. P.J. Porcher & Baya offer

“Two hundred and ten NEGROES, in families, accustomed to the culture of rice, cotton, and provisions…, AMONG WHICH ARE: Valuable CARPENTERS, Millwrights, Engineers, Coopers, Mill Hands, Blacksmiths, Boat Hands and House Servants.”

If Blacks were being sold as engineers, then where did they get their training? Were they taught by their slave masters and if so, where did the slave masters get their engineering training? We know that before 1862 there were no Land Grant Colleges that taught engineering and agriculture, so what were the other colleges teaching before then? As it turns out, there was only one college in America that taught engineering and that was the United States Military Academy at West Point, N. Y., founded in 1802. For the first half century, USMA graduates were largely responsible for overseeing the construction of the bulk of the nation’s initial railway lines, bridges, harbors and roads.

The majority of colleges were set up to train missionaries to spread “the Gospel.” Harvard was set up in 1650 to train Puritan ministers and Yale in 1701 to train ministers. In 1818, Congress authorized the newly created Alabama Territory to set aside a township for the establishment of a “seminary of learning,” now called the University of Alabama. None of these colleges at their founding taught engineering or practical sciences. They were all dedicated to studying the Bible and classical literature. In fact, the South did not even want the North to train any engineers or agriculturalists. The South had skilled slaves and had no need to train Whites to do such work, and they did not want the North to learn how to compete in agriculture. Once the South seceded in 1862, the states remaining in the Union immediately passed the Morrill Act in that same year, a legislative act that donated federal lands in each Union state for the establishment of the Land Grant Institutions.

However, over the last 100 years the success of the Land Grant Institutions in making agriculture more capital intensive instead of labor intensive has effectively increased the size of farms, while reducing the number of skilled farmers needed to produce the same or greater output.

In 1862, 90 percent of America’s population were farmers; however, in 1990 Drs. Dewitt Jones and Alfred L. Parks wrote:

“Today, the farm population accounts for only 2 percent of the total population; 2.6 percent of the employed labor force works in farm occupations, 2.0 percent of the GNP comes directly from farming, and 55 percent of employed farm residents work primarily in nonfarm jobs (U.S. Department of Agriculture 1988). Hence, the relative unimportance of agriculture as a source of employment and income, the rural-urban shift in population, and the skill requirements of today’s growth industries have rendered the original focus of the land grant mission obsolete.”

They continued:

“In addition, according to a study conducted for the University of Nevada-Reno College of Agriculture, agriculture majors will need more economics, business market analysis, sales and advertising, computer science, and business management courses to fill positions in the food and agriculture industry (Tevis). [Cheryl] Tevis further reports that the study found that perhaps the most striking weakness of undergraduate agriculture curricula is that a majority of the degree requirements focus on technical skills. Agribusiness firms offer very few opportunities to students possessing technical production skills but who are lacking in interpersonal and communication skills.”

Therefore, the mission of the modern Land Grant Institution is not to train farmers, but to produce employees for government and agribusiness corporations. Research at these institutions has changed the farming environment as well as the mix of faculty at the Black land-grant institutions. Before 1977, the mission of the Black land grants was primarily centered on teaching and extension. Teaching emphasized farming and technical skills. Extension programs trained teachers and farm advisors to go back to the countryside to pass on the latest improvements in farming practices to the farmers. The model for extension was based on Dr. George Washington Carver’s “moveable school” program, designed in the early 1900s to demonstrate the latest farm improvements to families too far away to visit the campus of the Tuskegee Institute.

Although the 1890 Land-Grant Institutions (also known as the “1890 Institutions”) received state funds for teaching and extension, the state funds allocated for research went to the White land-grant institutions. And since the southern states did not want to share any of these monies with Black land grants, Black college administrators appealed to the federal government for help. The Evans-Allen Act of 1977 provided capacity funding for food and agricultural research at the 17 Black land-grant colleges and universities plus Tuskegee Institute, in a manner similar to that provided to the White universities under the Hatch Act of 1887.

With the addition of federal funding for agricultural research and funds from other public and private sectors for other types of research came a change in how faculty were recruited and tenured. All young faculty members want to become “tenured,” which means that they are guaranteed a job for life on a particular campus. Before large quantities of research money were made available to Black land-grant colleges, each faculty member was evaluated based on teaching and extension. However, after these institutions became “research institutions,” more emphasis was put on research. A college wanted faculty that could bring in large research grants. So now to get tenured, a faculty member had to prove her research capabilities by showing how many research articles she could get published in peer-reviewed or “refereed” journals. After five years of working on the faculty as an assistant professor, you are then evaluated on whether you can be kept on the “plantation” (campus) as a full professor. If you did not have enough research publications, you could then be asked to leave.

This could explain the apparent reduction in Black college professors and a corresponding increase in White and foreign professors at the Black colleges as described by Venus Boston in her article “Black Faculty Fading from HBCUs.” Using data from the National Center for Educational Statistics, Boston reported: “In 1997 there were 7,966 full time Black faculty at HBCUs, but in 1999 this dropped to 7,887. During this same period the number of White full time faculty climbed from 3,640 to 3,761, and the number of other minority groups teaching at HBCUs climbed from 1,843 to 1,925.”

You might assume that this reduction in Black professors was due to their incompetence as teachers or researchers; however, there was, and is, a flawed system in place by which research is validated. When a researcher submits his paper to a “refereed journal,” his paper is given to a set of other tenured professors in that field from across the country. These reviewers are not given the name of the researcher or his university affiliation, thus supposedly eliminating bias or racism. However, when I was an assistant professor of agricultural economics at North Carolina A&T State University in the 1980s, I was at a meeting with other White agricultural economists and heard one say to the other, “Do you have the fonts for that journal?” If you check out the features of your word processing software, you will find over 100 “fonts” or styles of type to choose from. So this one conversation I overheard reveals how the “good old boy system” is used to control who keeps a job at a research institution. This knowledge about the importance of choosing the right font was not taught in the classroom. Today, unlike in the 1980s and 90s, a young professional can go to the Internet and be instructed that “If you are submitting an article for publication, the journal will have its own formatting and font requirements that you will need to follow.”

If you were not accepted by the White establishment and given the correct “font” to be used for a particular scholarly journal, then you might not have gotten your research published: no publications, no tenure—and you must move on to another university and start all over again. Over the last 40 years the mix of faculty and the very mission of the Black Land Grants have changed so much that we must look at “The Future of Farming and Food in America.”

(Dr. Ridgely A. Mu’min Muhammad, Agricultural Economist, National Student Minister of Agriculture, Manager of Muhammad Farms.)