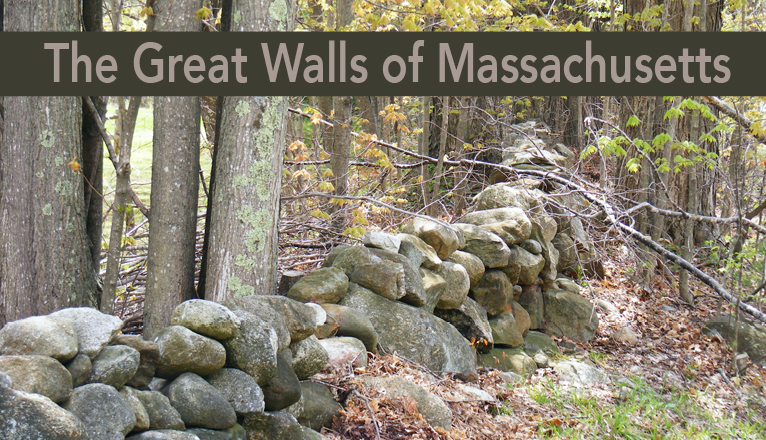

The Great Walls of Massachusetts

Evidence of Black Slavery in the Bay State

A drive along the byways of the Bay State reveals the ubiquitous presence of ancient stone walls stretching deep into and around the wooded landscape. Walls that have no apparent function today but centuries ago marked and divided the land, harnessed livestock, or warned off trespassers are the most permanent and lasting reminder of New England’s colonial past. The sheer amount of labor necessary for the erection of these walls is remarkable to consider. In 1850 Henry David Thoreau tried to fathom such a feat:

“We are never prepared to believe that our ancestors lifted large stones or built thick walls….[I]t suggests an energy and force of which we have no memorials.”

This is because Thoreau’s ancestors forced the Africans and Indians they enslaved to do this extraordinary backbreaking work. Massachusetts dignitary Robert Rantoul was more direct: “Many of the substantial stone fences marking the boundaries of early New England homesteads are the handiwork of slaves.”[1]

Even in the most remote sections of Massachusetts wilderness our Black ancestors were forced to erect these stone walls, hewing stones from glacial debris, transporting the huge stones over wilderness trails, and fashioning them into rock barriers at a white man’s command. They remain today as a testament to the presence of the Black man and the grueling labor he performed. Even as historians attempt to minimize or ignore the legacy of Black African slavery in Massachusetts, the clear and obvious evidence can be seen along almost every rural byway—etched in stone.[2]

NOTES:

[1] Robert S. Rantoul, “Abraham Lincoln,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 45, no. 2 (April 1909): 101.

[2] Robert M. Thorson, Stone By Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls (New York: Walker & Co., 2002), 6, 93, 102, 141, 198-99, 229. Thorson admits on three different pages of his book (pp. 6, 93, 102) that many of the “millions” (p. 102) of stone walls were built with the forced labor of African slaves, but does not mention this fact at all in his article in the Hartford Courant (“These Stones Belong to You and Me,” December 1, 2002, C1, 4). He writes that the stone walls are “the signatures of ordinary farm families who, acting together, built our nation.” This is a typical form of racial obfuscation used by many white academics. The material they write for other academics, as in their articles appearing in history journals and their monographs, offers a more complete account of their subject. That which is written for the general public, as in popular magazines, school textbooks, and newspapers, carefully omits those relevant facts that might undermine white supremacy’s fragile American cultural mythology.