The Debate Over Jews and Slavery: The Washington Post, 1993

“A Look At…Slavery Then and Now: Half-Truths and History”

“No element of a great tragedy is too small to be explored, particularly if it has been generally ignored.”

by David Mills, reporter, Washington Post

This article appeared in the Washington Post, October 17, 1993. It generated so much controversy that the Post’s ombudsman had to respond to it two weeks later (posted below). Despite their expiatory wording, both articles confirm the Nation of Islam position on the Jewish role in the slave trade.

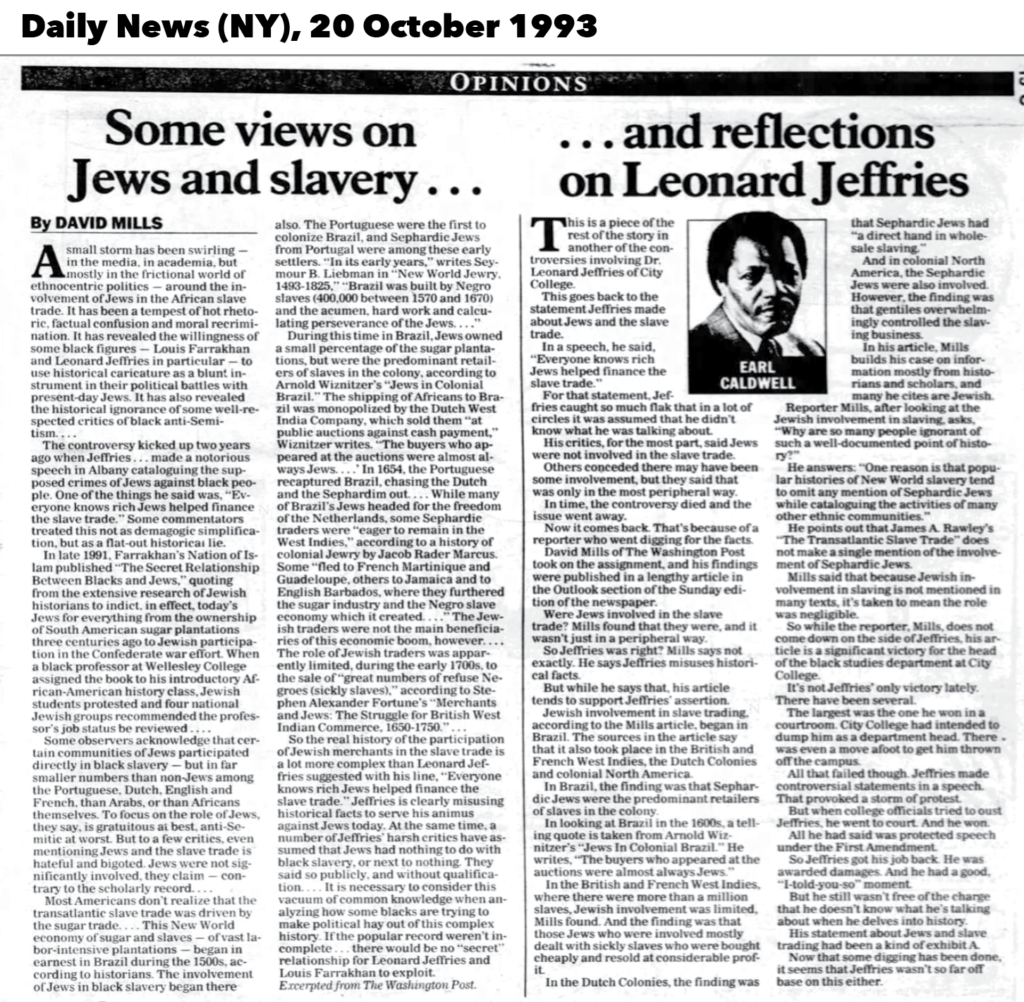

The controversy kicked up two years ago when Jeffries, an Afrocentric faculty member at the City College of New York, made a notorious speech in Albany, N.Y., cataloging the supposed crimes of Jews against black people. One of the things he said was, “Everyone knows rich Jews helped finance the slave trade.” Some commentators treated this not as demagogic simplification, but as a flat-out historical lie.

In late 1991, Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam published “The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews,” quoting from the extensive research of Jewish historians to indict, in effect, today’s Jews for everything from the ownership of South American sugar plantations three centuries ago to Jewish participation in the Confederate war effort. When a black professor at Wellesley College [Prof. Tony Martin] assigned the book to his introductory African-American history class, Jewish students protested and four national Jewish groups recommended the professor’s job status be reviewed. Both the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith have published rebuttals comparing “The Secret Relationship” to the most infamous works of antisemitic propaganda in the 20th century.

“There wouldn’t have been any slave trade at all,” syndicated columnist Nat Hentoff told me, “if it had not been for the middlemen, the chiefs of certain African tribes, who had captured people from other tribes and enslaved them. It’s important to say Africans have sold Africans. It’s important to know that.”

It is indeed important to understand all aspects of the history of slavery. For African-American people seeking to understand their place in the world, the history of slavery is as important as the history of the Holocaust for Jews. No element of a great tragedy is too small to be explored, particularly if it has been generally ignored.

Isn’t it also important, I asked Hentoff, to know that Jews bought and sold Africans?

“If it’s indeed the case, of course,” Hentoff said, acknowledging that he is not a scholar on the subject. “If you can nail that down, of course it would be important to know that.”

Most Americans, used to imagining slavery in terms of cotton fields and the Old South, don’t realize that the transatlantic slave trade sent Africans primarily to South America and the islands of the West Indies. According to one well-regarded census, 9.6 million Africans arrived alive in the so-called “New World” from the 16th century through the 19th century. Of these, less than 5 percent, 427,000, were brought to what is now the United States. Nearly 4 million went to Brazil, the largest single devourer of African labor. There, the average life span of a slave was a few years.

Most Americans don’t realize either that the transatlantic slave trade was driven by the sugar trade. Sugar cane was a scarce medicinal plant in medieval Europe. But when white colonizers started cultivating sugar in the fertile tropics of the Americas, it rapidly became a staple—and a great source of wealth for Europe’s shipping and trading powers. This New World economy of sugar and slaves—of vast, labor-intensive plantations—began in earnest in Brazil during the 1500s, according to historians. The involvement of Jews in black slavery began there also.

• Brazil. The Portuguese were the first to colonize Brazil, and Sephardic Jews from Portugal were among these early settlers. “In its early years,” writes Seymour B. Liebman in “New World Jewry, 1493-1825,” Brazil was built by Negro slaves (400,000 between 1570 and 1670) and the acumen, hard work and calculating perseverance of the Jews.”

• Brazil. The Portuguese were the first to colonize Brazil, and Sephardic Jews from Portugal were among these early settlers. “In its early years,” writes Seymour B. Liebman in “New World Jewry, 1493-1825,” Brazil was built by Negro slaves (400,000 between 1570 and 1670) and the acumen, hard work and calculating perseverance of the Jews.”

Some background is essential. The Sephardim—that is, the Jews of Spain and Portugal—had flourished for centuries in the Iberian peninsula. By 1497, they made up an estimated 20 percent of Portugal’s population of 1 million. But that year, the king of Portugal compelled the Jews to convert to Christianity. (Spain had similarly forced its Jews to convert or flee five years earlier.) While many Jews left Portugal, others indeed were baptized and became “New Christians.” Despite the church’s persecution, some continued to practice Judaism in secret; they came to be known as “Marranos.”

New Christians were drawn to Brazil, in part because it was far from the seat of the Inquisition, but also because the South American colony was a place where the Sephardim could apply their established expertise in trade and sugar cultivation. Soon a Sephardic community thrived in Brazil’s pivotal port city of Recife. When the Dutch—then unique in Europe for their religious tolerance—took control of Brazil in 1630, the Marranos there were able to practice Judaism openly again.

During this time in Brazil, Jews owned a small percentage of the sugar plantations but were the predominant retailers of slaves in the colony, according to Arnold Wiznitzer’s “Jews in Colonial Brazil.” The shipping of Africans to Brazil was monopolized by the Dutch West India Company, which sold them “at public auctions against cash payment,” Wiznitzer writes. “The buyers who appeared at the auctions were almost always Jews.” These brokers then sold slaves to plantation owners on credit. More than 23,000 Africans were shipped to Brazil between 1636 to 1645, Wiznitzer says, a period when perhaps half of the 3,000 white civilians living there were Jews.

• The British and French West Indies. In 1654, the Portuguese recaptured Brazil, chasing the Dutch and the Sephardim out—an event that would affect the destiny of Jews and Africans in the New World.

While many of Brazil’s Jews headed for the freedom of the Netherlands, some Sephardic traders were “eager to remain in the West Indies,” according to a history of colonial Jewry by Jacob Rader Marcus, longtime director of the American Jewish Archives. Some “fled to French Martinique and Guadeloupe, others to Jamaica and to English Barbados, where they furthered the sugar industry and the Negro slave economy which it created,” Marcus writes.

The Jewish refugees from Brazil, as University of Kansas economic historian Richard B. Sheridan has pointed out, “were masters of sugar technology and taught the English the art of sugar making.” The sugar colonies of Barbados and Jamaica grew to become jewels of the British empire during the 1700s. An estimated 1.1 million Africans were shipped to these islands over the entire course of the slave trade.

The Jewish traders were not the main beneficiaries of this economic boom, however. One British historian notes: “Most Jews in Barbados and Jamaica in the 18th century were small men, shopkeepers….The sugar trade became increasingly concentrated in the hands of the sugar-planters’ agents in London, a restricted and confined circle. [Jews] did not participate.” The role of Jewish traders was apparently limited, during the early 1700s, to the sale of “great numbers of ‘refuse’ Negroes (sickly slaves),” according to Stephen Alexander Fortune’s “Merchants and Jews: The Struggle for British West Indian Commerce, 1650-1750.” These Africans, bought cheaply, were resold “at considerable profit” once healthy.

The role of Jewish merchants in the slave economy of Martinique and Guadeloupe was eventually restricted as well. Initially, “the Sephardi emigres from Brazil…engage[d] both in plantation agriculture and trade, exporting sugar and tobacco to Europe and importing slaves and cloth,” according to Jonathan Israel’s history, “European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism, 1550-1750.” The Catholic French, however, ordered the expulsion of all Jews from these islands in 1685, thus virtually ending their role in the trade.

• The Dutch Colonies. The Jewish and Dutch refugees from Brazil also landed in Suriname in the late 17th century, establishing it as a sugar colony. This small piece of South America, as Harvard University historian Eugene Genovese has noted, would be the one and only place where Jews constituted a substantial planter class. Genovese cited one scholar’s finding that 115 of Suriname’s 400 sugar estates in 1730 were owned by Jews.

The island of Curaçao, a pivotal Dutch distribution center off the coast of Venezuela, was the site of the largest Jewish settlement in the New World. The Sephardic community there numbered almost 2,000 by the mid-1700s, constituting about half of the white population. Curaçao’s Jews “prospered early through shipping and slave-trading,” writes David Lowenthal in “West Indian Societies.” Isaac S. and Suzanne A. Emmanuel, historians of Curaçaoan Jewry, report that “[a]lmost every Jew bought from one to nine slaves for his personal use or for eventual resale.” Later, Curaçaoan Jews became, as Stephen Fortune writes, “the predominant insurance underwriters for ships plying the Caribbean”—including slave ships.

Under the auspices of the Dutch, Sephardic Jews also had a direct hand in wholesale slaving. As Arnold Wiznitzer has pointed out, Jews in Amsterdam owned as much as 10 percent of the stock in the Dutch West India Company, the great slave-shipping enterprise that helped launch the Netherlands to international commercial prominence during the 1600s. But the French and English monopoly trading companies, which eventually dominated the shipping of Africans to New World colonies, excluded Jews from that level of the trade.

• Colonial North America. The far-flung Sephardic “trade diaspora” in the Caribbean led ultimately to the founding of Jewish communities in North America. Before the Revolutionary War, the largest settlement of Jews in the colonies—perhaps as many as 1,000 by 1760—was in the bustling port city of Newport, R.I. Aaron Lopez, formerly a Marrano in Portugal, laid the first cornerstone of the Newport congregation’s synagogue in 1759. (The building is now a historic site, the oldest synagogue in the United States.) Lopez later became a shipper of legendary prosperity. Black slaves were among his cargoes, as his biographer, Stanley F. Chyet, has noted.

• Colonial North America. The far-flung Sephardic “trade diaspora” in the Caribbean led ultimately to the founding of Jewish communities in North America. Before the Revolutionary War, the largest settlement of Jews in the colonies—perhaps as many as 1,000 by 1760—was in the bustling port city of Newport, R.I. Aaron Lopez, formerly a Marrano in Portugal, laid the first cornerstone of the Newport congregation’s synagogue in 1759. (The building is now a historic site, the oldest synagogue in the United States.) Lopez later became a shipper of legendary prosperity. Black slaves were among his cargoes, as his biographer, Stanley F. Chyet, has noted.

Gentiles, however, overwhelmingly controlled the slaving business in colonial America. Rhode Island’s Sephardic merchant-shippers were known mainly for their prominence in the business of selling oil from sperm whales used in candlemaking.

So the real history of the participation of Jewish merchants in the slave trade is a lot more complex than Leonard Jeffries suggested with his line, “Everyone knows rich Jews helped finance the slave trade.” Jeffries is clearly misusing historical facts to serve his animus against Jews today.

At the same time, a number of Jeffries’ harsh critics have assumed that Jews had nothing to do with black slavery, or next to nothing. They said so publicly, and without qualification, during the Jeffries controversy.

Jonathan Yardley wrote in The Washington Post that Jeffries, on this point, had “turned history upside down.” When I asked him what part Jews did have in trafficking Africans, Yardley (a self-described WASP) didn’t know but said it would have been “relatively minor.”

A.M. Rosenthal of the New York Times wrote that Jeffries “says in a public forum that the Jews financed the slave trade. That is not quite the equivalent of [the accusation] Christ-killer, but coming close, make no mistake.” I asked Rosenthal too what actual role Jews played in black slavery. “There was none,” he replied. “Except for the most peripheral way. If at all.”

Jim Sleeper of the New York Daily News said he talked to four scholars before concluding, as he wrote in a critique of Jeffries for the Nation, that Jews merely had a “marginal” involvement in the slave trade.

How about in Brazil? I asked him.

“They would have had an extremely marginal, extremely minor role,” Sleeper told me. Did Jews own sugar plantations? “I don’t know.” Sleeper finally acknowledged, “I don’t know anything about Brazil.”

Why are so many people ignorant of such a well-documented point of history? One reason is that popular histories of New World slavery tend to omit any mention of Sephardic Jews while cataloging the activities of many other ethnic communities. In “The Rise and Fall of Black Slavery,” C. Duncan Rice mentions the “Dutch refugees” who established the sugar industry in Barbados, and the “planters of Dutch Surinam” who, “with characteristic Flemish practicality,” started up a sugar colony with a full force of black slaves. But he does not mention the Portuguese Jews among these Dutch. James A. Rawley’s “The Transatlantic Slave Trade” has not a single mention over the course of 452 pages of the involvement of Sephardic Jews.

The holes in the popular record have led to misunderstanding. In a 1991 article in the Jewish monthly Midstream, headlined “An Old/New Libel: Jews in the Slave Trade,” historian Saul Friedman noted that “Jews are remarkably absent from major texts” on New World slavery and cited seven history books by name. For Friedman, this constitutes proof that the role of Jews was negligible. Actually, he merely demonstrates the inadequacies of such “major texts.”

It is necessary to consider this vacuum of common knowledge when analyzing how some blacks are trying to make political hay out of this complex history. If the popular record weren’t incomplete—that is, if everyone already knew that Sephardic merchants and planters had played a small but significant role in the New World slave trade—there would be no “secret” relationship for Leonard Jeffries and Louis Farrakhan to exploit.

[end]

Response by Washington Post Ombudsman, Joann Byrd

The Washington Post, October 31, 1993, Sunday, Final Edition

The Timing Of News

When a painful, volatile issue is made worse by disinformation and misinformation, maybe it does fall to a newspaper to make sure all sides start from the same facts.

And that was the goal of “Half-Truths and History: The Debate Over Jews and Slavery,” which appeared two weeks ago in Outlook. But this time at least, it’s not so simple as that.

Post Style reporter David Mills said last week that he wanted his essay to report the historical facts that “many otherwise well-educated people don’t know. The fact that they don’t know this is distorting the current political discussion.”

The current political discussion being the argument that arose after the Nation of Islam and Leonard Jeffries, a City College of New York professor, claimed in 1991 that Jews were heavily involved in the New World slave trade.

The Outlook article’s starting point was that it is not true that Jews were disproportionately involved, but it’s also inaccurate to say Jews had no role whatever.

The piece acted as a truth squad, checking the facts of Jeffries’ claims, the Nation of Islam book “The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews” and the commentators who condemned those distortions but got it wrong themselves. It cited a list of historians to show that Sephardic Jews played “a small but significant role in the New World slave trade.” Many Jews and intellectuals have long acknowledged this; a lot of the rest of us didn’t know much about it.

Two problems with the Outlook piece invited the criticism it has received:

There is no fresh news on this debate. If this piece had been published two years ago, its existence might have made sense to readers: The Nation of Islam book and Mr. Jeffries’ comments were then in the daily news report; the author aimed to provide reliable information readers could use to evaluate what they saw elsewhere in the paper.

But the essay gave no newer news peg than the 1991 controversies. So it looked to readers like a political statement, an out-of-the-blue declaration that Jews were involved in the slave trade.

So critics may have missed the intent and the content while speculating on what motivated the writer and editors to put this in The Post. They called it divisive, antagonistic, antisemitic or, at least, suspicious.

Mr. Mills is correct when he responds: There is no “good” time to run this essay. Two years ago, amid news, The Post would have been perceived as joining the fight; “when there’s no news, it looks like you’re picking a fight,” he notes.

(Mr. Mills did write a draft in 1991, and if it had run then, it might well have seemed designed to defend the extremists. He offered the piece again this summer when Mr. Jeffries was back in the news, being reinstated to head CCNY black studies. It took months of internal debate and editing to get the piece in the paper.)

The other objection is this: The piece gave too much regard to an isolated slice of a much larger and tangled history. In focusing on the role of Jews (and not, say, on the role of left-handers) it seemed to imply the extremists’ position is both relevant and worth serious attention. (Mr. Mills responds, figuratively and accurately, that no one has publicly brought up the role of left-handed people.)

The other objection is this: The piece gave too much regard to an isolated slice of a much larger and tangled history. In focusing on the role of Jews (and not, say, on the role of left-handers) it seemed to imply the extremists’ position is both relevant and worth serious attention. (Mr. Mills responds, figuratively and accurately, that no one has publicly brought up the role of left-handed people.)

For Outlook editor Jodie Allen, there’s value in setting down the reliable record: “Maybe we can get beyond this if the facts are known.”

All of this asks a larger and difficult question: Was there a way to report what’s true without aiding and abetting hate?

My bias says, always, that newspapers are in the information business, and what’s usually needed is more reporting and more context.

Even two years late, the paper could have reported this with less risk of fueling hostilities and without readers being distracted by wondering what The Post was up to. The paper could have added the rest of the story.

Picture a companion report outlining the whole slave trade, maybe excerpts from an authoritative history (or two or three). The overview, I think, would detail how individuals of just about every religion, race and nationality were a part of this sorrowful disgrace.