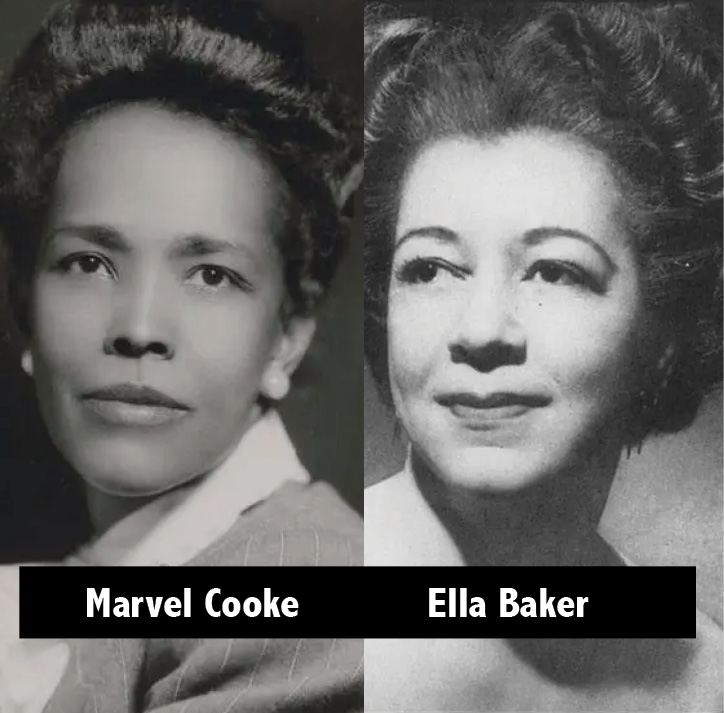

The Bronx Slave Market, The Crisis [NAACP], September, 1935

In 1935, two Black journalists exposed how Jews exploited Black domestic workers.

The Crisis, November, 1935

In the Bronx, northern borough of New York City known for its heavy Jewish population, exists a street corner market for domestic servants where Negro women are “rented” at unbelievably low rates for house work

THE Bronx Slave Market! What is it? Who are its dealers? Who are its victims? What are its causes? How far does its stench spread? What forces are at work to counteract it?

Any corner in the congested sections of New York City’s Bronx is fertile soil for mushroom “slave marts.” The two where the traffic is heaviest and the bidding is highest are located at 167th street and Jerome avenue and at Simpson and Westchester avenues.

Symbolic of the more humane slave block is the Jerome avenue “market.” There, on benches surrounding a green square, the victims wait, grateful, at least, for some place to sit. In direct contrast is the Simpson avenue “mart,” where they pose wearily against buildings and lamp posts, or scuttle about in an attempt to retrieve discarded boxes upon which to rest.

Again, the Simpson avenue block exudes the stench of the slave market at its worst. Not only is human labor bartered and sold for slave wage, but human love also is a marketable commodity. But whether it is labor or love that is sold, economic necessity compels the sale. As early as 8 a.m. they come; as late as 1 p.m. they remain.

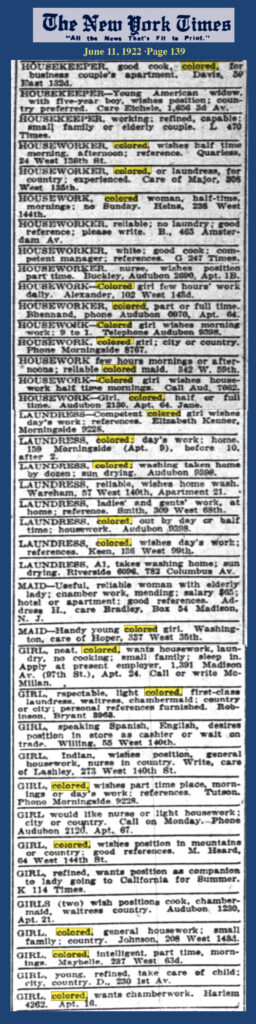

Rain or shine, cold or hot, you will find them there—Negro women, old and young—sometimes bedraggled, sometimes neatly dressed—but with the invariable paper bundle, waiting expectantly for Bronx housewives to buy their strength and energy for an hour, two hours, or even for a day at the munificent rate of fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, or, if luck be with them, thirty cents an hour. If not the wives themselves, maybe their husbands, their sons, or their brothers, under the subterfuge of work, offer worldly-wise girls higher bids for their time.

Who are these women? What brings them here? Why do they stay? In the boom days before the onslaught of the depression in 1929, many of these women who are now forced to bargain for day’s work on street corners, were employed in grand homes in the rich Eighties, or in wealthier homes in Long Island and Westchester, at more than adequate wages. Some are former marginal industrial workers, forced by the slack in industry to seek other means of sustenance. In many instances there had been no necessity for work at all. But whatever their standing prior to the depression, none sought employment where they now seek it. They come to the Bronx, not because of what it promises, but largely in desperation.

Paradoxically, the crash of 1929 brought to the domestic labor market a new employer class. The lower middle-class housewife, who, having dreamed of the luxury of a maid, found opportunity staring her in the face in the form of Negro women pressed to the wall by poverty, starvation and discrimination.

Where once color was the “gilt edged” security for obtaining domestic and personal service jobs, here, even, Negro women found themselves being displaced by whites. Hours of futile waiting in employment agencies, the fee that must be paid despite the lack of income, fraudulent agencies that sprung up during the depression, all forced the day worker to fend for herself or try the dubious and circuitous road to public relief.

As inadequate as emergency relief has been, it has proved somewhat of a boon to many of these women, for with its advent, actual starvation is no longer their ever-present slave driver and they have been able to demand twenty-five and even thirty cents an hour as against the old fifteen and twenty cent rate. In an effort to supplement the inadequate relief received, many seek this open market.

And what a market! She who is fortunate (?) enough to please Mrs. Simon Legree’s scrutinizing eye is led away to perform hours of multifarious household drudgeries. Under a rigid watch, she is permitted to scrub floors on her bended knees, to hang precariously from window sills, cleaning window after window, or to strain and sweat over steaming tubs of heavy blankets, spreads and furniture covers.

Fortunate, indeed, is she who gets the full hourly rate promised. Often, her day’s slavery is rewarded with a single dollar bill or whatever her unscrupulous employer pleases to pay. More often the clock is set back for an hour or more. Too often she is sent away without any pay at all.

How It Works

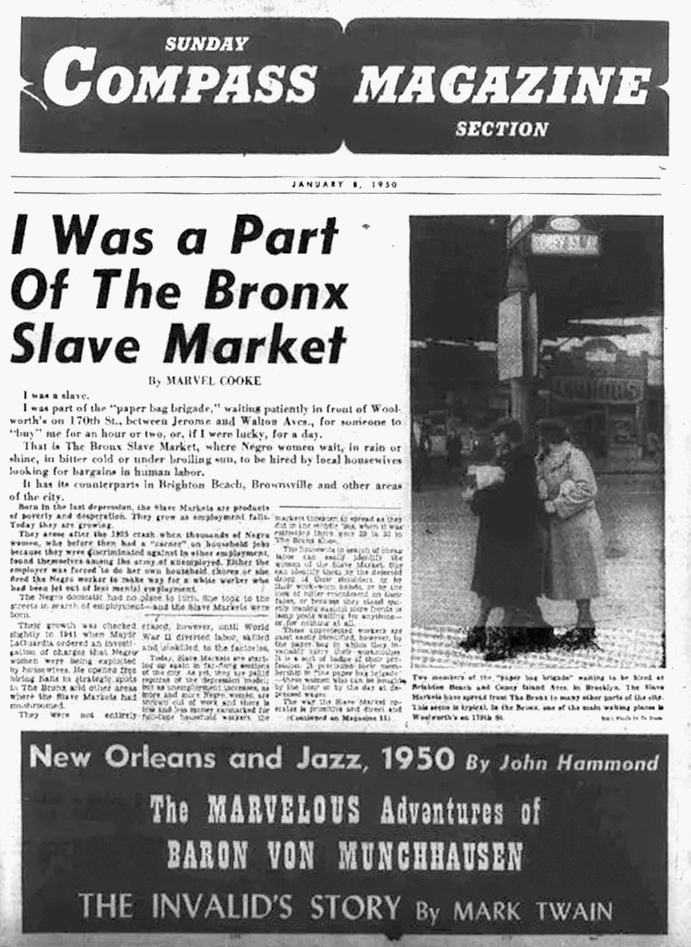

We invaded the ”market” early on the morning of September 14. Disreputable bags under arm and conscientiously forlorn, we trailed the work entourage on the West side “slave train,” disembarking with it at Simpson and Westchester avenues. Taking up our stand outside the corner flower shop whose show window offered gardenias, roses and the season’s first chrysanthemums at moderate prices, we waited patiently to be “bought.”

We got results in almost nothing flat. A squatty Jewish housewife, patently lower middle class, approached us, carefully taking stock of our “wares.”

“You girls want work?”

“Yes.” We were expectantly noncommittal.

“How much you work for?”

We begged the question, noting that she was already convinced that we were not the “right sort.” “How much do you pay?”

She was walking away from us. “I can’t pay your price,” she said and immediately started bargaining with a strong, seasoned girl leaning against the corner lamp post. After a few moments of animated conversation, she led the girl off with her. Curious, we followed them two short blocks to a dingy apartment house on a side street.

We returned to our post. We didn’t t seem to be very popular with the other “slaves”. They eyed us suspiciously. But, one by one, as they became convinced that we were one with them, they warmed up to friendly sallies and answered our discreet questions about the possibilities of employment in the neighborhood.

Suddenly it began to rain, and we, with a dozen or so others, scurried to shelter under the five-and-ten doorway midway the block. Enforced close communion brought about further sympathy and conversation from the others. We asked the brawny, neatly dressed girl pressed close to us about the extent of trade in the “oldest profession” among women.

“Well,” she said, “there is quite a bit of it up here. Most of ‘those’ girls congregate at the other corner.” She indicated the location with a jerk of her head.

“Do they get much work?” we queried.

“Oh, quite a bit,” she answered with a finality which was probably designed to close the conversation. But we were curious and asked her how the other girls felt about it. She looked at us a moment doubtfully, probably wondering if we weren’t seeking advice to go into the “trade” ourselves.

“Well, that’s their own business. If they can do it and get away with it, it’s all right with the others.” Or probably she would welcome some “work” of that kind herself.

”Sh-h-h.” The wizened West Indian woman whom we had noticed, prior to the rain, patrolling the street quite belligerently as if she were daring someone not to hire her, was cautioning us. She explained that if we kept up such a racket the store’s manager would kick all of us out in the rain. And so we continued our conversation in whispered undertone.

“Gosh. I don’t like this sort of thing at all.” The slender brown girl whom we had seen turn down two jobs earlier in the morning, seemed anxious to talk. “This is my first time up here—and believe me, it is going to be my last. I don’t like New York nohow. If I don’t get a good job soon, I’m going back home to Kansas City.” So she had enough money to travel, did she?

Cut Rate Competition

The rain stopped quite as suddenly as it started. We had decided to make a careful survey of the district to see whether or not there were any employment agencies in the section. Up one block and down another we tramped, but not one such institution did we encounter. Somehow the man who gave us a sly “Hello, babies!” as he passed was strangely familiar. We realized two things about him—that he had been trailing us for some time and that he was manifestly, plain clothes notwithstanding, one of “New York’s finest.”

Trying to catch us to run us in for soliciting, was he? From that moment on, it was a three-cornered game. When we separated he was at sea. When we were together, he grinned and winked at us quite boldly….

We sidled up to a friendly soul seated comfortably on an upturned soap-box. Soon an old couple approached her and offered a day’s work with their daughter way up on Jerome avenue. They were not in agreement as to how much the daughter would pay—the old man said twenty-five cents an hour—tile old lady scowled and said twenty. The car fare, they agreed, would be paid after she reached her destination. The friendly soul refused the job. She could afford independence, for she had already successfully bargained for a job for the following day. She said to us, after the couple started negotiations with another woman, that she wouldn’t go way up on Jerome avenue on a wild goose chase for Mrs. Roosevelt, herself. We noted, with satisfaction, that the old couple had no luck with any of the five or six they contacted.

It struck us as singularly strange, since it was already 10:30, that the women still lingered, seemingly unabashed that they had not yet found employment for a day. We were debating whether or not we should leave the “mart” and try again another day, probably during the approaching Jewish holidays at which time business is particularly flourishing, when, suddenly, things looked up again. A new batch of “slaves” flowed down the elevated steps and took up their stands at advantageous points.

The friendly soul turned to us, a sneer marring the smooth roundness of her features. “Them’s the girls who makes it bad for us. They get more jobs than us because they will work for anything. We runned them off the corner last week.” One of the newcomers was quite near us and we couldn’t help but overhear the following conversation with a neighborhood housewife.

“You looking for work?”

“Yes ma’am.”

“How much you charge?”

“I’ll take what you will give me.” . . . What was this? Could the girl have needed work that badly? Probably. She did look run down at the heels….

“All right. Come on. I’ll give you a dollar.” Cupidity drove beauty from the arrogant features. The woman literally dragged her “spoil” to her “den.” . . . But what of the girl? Could she possibly have known what she was letting herself in for? Did she know how long she would have to work for that dollar or what she would have to do? Did she know whether or not she would get lunch or car fare? Not any more than we did. Yet, there she was, trailing down the street behind her “mistress.”

“You see,” philosophized the friendly soul. “That’s what makes it bad for the rest of us. We got to do something about those girls. Organize them or something.” The friendly soul remained complacent on her up-turned box. Our guess was that if the girls were organized, the incentive would come from some place else.

Business in the ”market” took on new life. Eight or ten girls made satisfactory contacts. Several women—and men—approached us, but our price was too high or we refused to wash windows or scrub floors. We were beginning to have a rollicking good time when rain again dampened our heads and ardor. We again sought the friendly five-and-ten doorway.

“For Five Bucks a Week”

We became particularly friendly with a girl whose intelligent replies to our queries intrigued us. When we were finally convinced that there would be no more “slave” barter that day, we invited her to lunch with us at a near-by restaurant. After a little persuasion, there we were, Millie Jones between us, refreshing our spirits and appetites with hamburgers, fragrant with onions, and coffee. We found Millie an articulate person. It seems that, until recently, she had had a regular job in the neighborhood. But let her tell you about it.

“Did I have to work? And how! For five bucks and car fare a week. Mrs. Eisenstein had a six-room apartment lighted by fifteen windows. Each and every week, believe it or not, I had to wash every one of those windows. If that old hag found as much as the teeniest speck on any one of ’em, she’d make me do it over. I guess I would do anything rather than wash windows. On Mondays I washed and did as much of the ironing as I could. The rest waited over for Tuesday. There were two grown sons in the family and her husband. That meant that I would have at least twenty-one shirts to do every week. Yeah, and ten sheets and at least two blankets, besides. They all had to be done just so, too. Gosh, she was a particular woman.

“There wasn’t a week, either, that I didn’t have to wash up every floor in the place and wax it on my hands and knees. And two or three times a week I’d have to beat the mattresses and take all the furniture covers off and shake ’em out. Why, when I finally went home nights, I could hardly move. One of the sons had “hand trouble” too, and I was just as tired fighting him off, I guess, as I was with the work.

“Say, did you ever wash dishes for an Orthodox Jewish family?” Millie took a long, sibilant breath. “Well, you’ve never really washed dishes, then. You know, they use a different dishcloth for everything they cook. For instance, they have one for “milk” pots in which dairy dishes are cooked, another for glasses, another for vegetable pots, another for meat pots, and so on. My memory wasn’t very good and I was always getting the darn things mixed up. I used to make Mrs. Eisenstein just as mad. But I was the one who suffered. She would get other cloths and make me do the dishes all over again.

“How did I happen to leave her? Well, after I had been working about five weeks, I asked for a Sunday off. My boy friend from Washington was coming up on an excursion to spend the day with me. She told me if I didn’t come in on Sunday, I needn’t come back at all. Well, I didn’t go back. Ever since then I have been trying to find a job. The employment agencies are no good. All the white girls get the good jobs.

“My cousin told me about up here. The other day I didn’t have a cent in my pocket and I just had to find work in order to get back home and so I took the first thing that turned up. I went to work about 11 o’clock and I stayed until 5:00—washing windows, scrubbing floors and washing out stinking baby things. I was surprised when she gave me lunch. You know, some of ’em don’t even do that. What I got through, she gave me thirty-five cents. Said she took a quarter out for lunch. Figure it out for yourself. Ten cents an hour!

Miniature Economic Battlefront

The real significance of the Bronx Slave Market lies not in a factual presentation of its activities; but in focusing attention upon its involved implications. The “mart” is but a miniature mirror of our economic battle front.

To many, the women who sell their labor thus cheaply have but themselves to blame. A head of a leading employment agency bemoans the fact that these women have not “chosen the decent course” and declares: “The well-meaning employment agencies endeavoring to obtain respectable salaries and suitable working conditions for deserving domestics are finding it increasingly difficult due to the menace and obstacles presented by the slavish performances of the lower types of domestics themselves, who, unlike the original slaves who recoiled from meeting their masters, rush to meet their mistresses.”

The exploiters, judged from the districts where this abominable traffic flourishes, are the wives and mothers of artisans and tradesmen who militantly battle against being exploited themselves, but who apparently have no scruples against exploiting others.

The general public, though aroused by stories of these domestics, too often think of the problems of these women as something separate and apart and readily dismisses them with a sigh and a shrug of the shoulders.

The women, themselves present a study in contradictions. Largely unaware of their organized power, yet ready to band together for some immediate and personal gain either consciously or unconsciously, they still cling to that American illusion that any one who is determined and persistent can get ahead.

The roots, then of the Bronx Slave Market spring from: (1) the general ignorance of and apathy towards organized labor action; (2) the artificial barriers that separate the interest of the relief administrators and investigators from that of their “case loads,” the white collar and professional worker from the laborer and the domestic; and (3) organized labor’s limited concept of exploitation, which permits it to fight vigorously to secure itself against evil, yet passively or actively aids and abets the ruthless destruction of Negroes.

To abolish the market once and for all, these roots must be torn away from their sustaining soil. Certain palliative and corrective measures are not without benefit. Already the seeds of discontent are being sown.

The Women’s Day Workers and Industrial League, organized sixteen years ago by Fannie Austin, has been, and still is, a force to abolish the existing evils in day labor. Legitimate employment agencies have banded together to curb the activities of the racketeer agencies and are demanding fixed minimum and maximum wages for all workers sent out. Articles and editorials recently carried by the New York Negro press have focused attention on the existing evils in the “slave market.”

An embryonic labor union now exists in the Simpson avenue “mart.” Girls who persist in working for less than thirty cents an hour have been literally run off the corner. For the recent Jewish holiday, habitues of the “mart” actually demanded and refused to work for less than thirty-five cents an hour.

The Crisis [NAACP], September, 1935