The Black Press—No Longer What It Was

The Black press is presumed to be a voice for the oppressed, challenging the daily racial insults that beset the Black race in America. Like the press of the Asians, Jews, Italians, Irish and others, the Black press has acted, more or less, as a political organizer, a cultural informer, a social commentator, and an economic engine, always with race solidarity and the protection and progress of their own in mind.

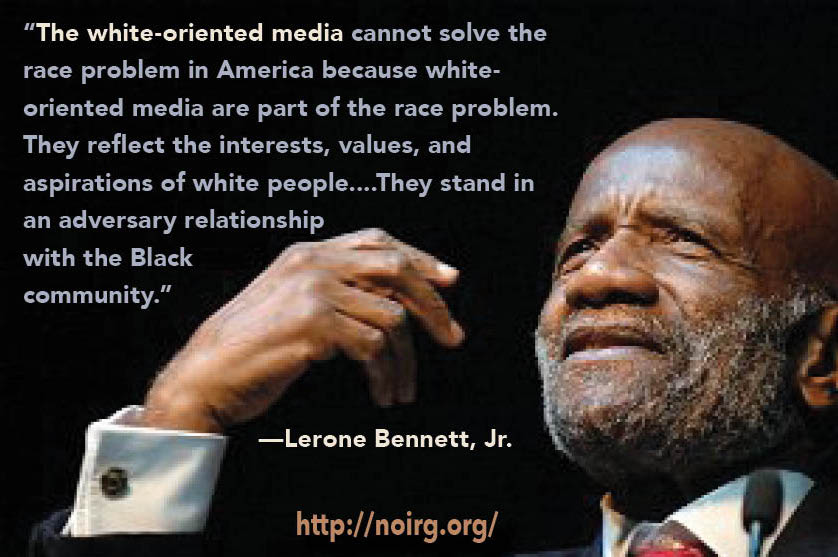

The current crop of “elite” negro journalists that appear daily on network news have but one apparent qualification—an almost total lack of critical analysis and objectivity. So dutiful are they in their nightly reading of their prepared scripts that Black American viewers stand in awe at their unwavering submission to the government line. The great Ebony editor Lerone Bennett, Jr., said:

“The white-oriented media cannot solve the race problem in America because white-oriented media are part of the race problem. They reflect the interests, values, and aspirations of white people….They stand in an adversary relationship with the black community.”

“The white-oriented media cannot solve the race problem in America because white-oriented media are part of the race problem. They reflect the interests, values, and aspirations of white people….They stand in an adversary relationship with the black community.”

The famous black faces are just fine with that reality. They are, of course, getting paid.

But once upon a time—before integration—the earliest Black newspapers were born out of the need to respond to the incessant racial slander and genocidal violence by pro-slavery American whites. As early as 1827, Blacks began the printed propaganda war for their own freedom from slavery and discrimination, providing, for the first time, “a judicious and proper advocacy” of Black interests. “We wish to plead our own cause,” John B. Russwurm passionately wrote in the first edition of the Freedom’s Journal. “Too long have others spoken for us. Too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentation in things which concern us dearly…”

Soon Black newspapers sprang up all across America to defend Black rights and advance Black interests. In 1880, when Blacks in Clarksville, Tennessee, burned down the white business district in retaliation for a lynching, the Chicago Conservator responded in the highest American revolutionary tradition: “We are proud to see them have the manhood to be the willing witnesses of [racism’s] destruction.” The editors further pressed the issue with a Nat Turner-like militancy unknown today:

The people of Clarksville have broken the ice, God grant it may extend from Virginia to Texas….[W]e warn the southern whites that they need not expect such one-sided scenes of butchery in the future.

The Selma Independent likewise published an article in 1889 in which the Black author boldly declared to the white man that

[w]ere you to leave this South land, in twenty years it would be one of the grandest sections of the globe. We would show you mossback crackers how to run a country….You have predicted [a] race war, and we hope, as God intends, that we will be strong enough to wipe you out of existence and hardly leave enough of you to tell the story.

Josiah T. Settle could proudly report as far back as 1895 that the Black press “has made it impossible to oppress [the Black] race in secrecy and silence, and has established a sure and permanent medium through which the doings for and against [the] race are given to the world.” And that tradition continued.

The Boston Guardian, founded in 1901 by William Monroe Trotter, and Robert Abbott’s Chicago Defender, founded in 1905, encouraged Blacks to assert their God-given rights and championed the mass northward migrations of Blacks away from lynch mobs and virtual slavery. Marcus Garvey’s Negro World was the literary accompaniment to the largest self-motivated Black movement in America’s history up to that time. Blacks even formed the Associated Negro Press wire service, with correspondents and contributors in all of the United States and forty-five countries and news printed in both French and English.

The greatest of ALL these independents was the Nation of Islam’s 48-page weekly Muhammad Speaks newspaper. The paper sent reporters to Cuba, the Soviet Union, Mexico, Mongolia, Puerto Rico; to Africa to tell of the freedom struggles of South Africans, Mozam- biqans, Zimbabweans, and Angolans; to England, Mexico, and both Germanys—even North Vietnam and North Korea and other places the U.S. government said Americans were not permitted to go.

But a funny thing happened on the way to integration. With some prominent exceptions, the Black press transformed itself from an independent voice of homegrown Black freedom strategies, to a reactionary promoter of others’ agendas for Black people. What was once a fearless and revolutionary race defender, opinion leader, and autonomous Black institution became cowed by promises of acceptance in the white world, which it traded for its militancy and fire. The editor of the NAACP’s Crisis magazine once wrote in the spirit of his radical predecessors that it was Black men’s “Divine Right” to “kill lecherous white invaders of their homes and then take their lynching gladly like men. It’s worth it.” But when, a few years later, the NAACP’s integrationist journal was banned from the reading rooms of the U.S. military, a fearful organization official assured the white Washington rulers that “no pains will be spared to make all future issues of this magazine comply with the wishes of the Government both in letter and spirit.”

One prominent figure in the history of the Black press seemed anxious to surrender its independence to white authority. Claude Barnett, founder of the Associated Negro Press, thought it was “a shame” that Blacks and whites had separate newspapers and separate wire services, and favorably predicted his own demise!

We are working toward the end that someday there will be no need for my news service and no need for anything else—including society—which at present the white community does not allow us to share.

The Black newspapers today appear content to be a supplement to the white news rather than strive to challenge seriously the daily racial assaults and blatant propaganda of the white “majors.” Just as the Black community became more politicized and more comfortable with activism in the 1960s, its newspapers abdicated their leadership role. By the Black press’s own admission, opportunities to land big advertising accounts from major corporations were too tempting to pass up. One executive said that the Black press “finds itself trying not to be too conservative for the black revolutionaries, and not too revolutionary for white conservatives upon whom it depends for advertising.”

Another executive, of the Afro-American, stated the obvious: “In earlier years, black newspapers were spearheads of protest. Today we’re much more informational.” The vice president at Sengstacke Newspapers agreed with his colleagues that “black publishers have to make sure they don’t become too revolutionary in tone for fear of losing those new white accounts.” An Amsterdam News executive concurred: “we have not kept up with the black revolution as we should have. But you’ve got to realize that we don’t see our role as leaders. We are not out to revolutionize.”

The Black press’s surrender to the lure of white financial sponsorship constitutes a major tragedy in the struggle for Black empowerment. This new orientation was soon reflected in the neutered editorial policies of the major “Black” newspapers. They caved ENTIRELY to the wicked COVID-19 Depopulation agenda becoming no more than publicity agents for the high-paid charlatan Anthony Fauci, the CDC, the FDA, Pfizer, and J&J. They watched and barely bleated as Israel murdered 35,000 innocents and bombed their world to oblivion.

But that was expected. A study of their coverage of the civil-rights-era Black revolution found that—as in the coverage by their white counterparts—“Black power and militancy were treated negatively” in most editorials. They opposed the Black student sit-in movement; they opposed “separatism, extremism and Stokely Carmichael”; they condemned the “ghetto riots” quicker than their causes; and they were deemed to be “overwhelmingly integrationist.” This trend only accelerated in the 1960s. As far back as the 1920s, the editorial content of some, mostly NAACP-influenced, negro newspapers began to reflect a zeal for integration and a pronounced hostility toward Black independence.

In balancing its responsibility to its newfound corporate suitors with its forsaken role as strategic propagandist for Black empowerment, the Black press found its niche in the public debate condemning injustice, but carefully avoiding advocating that Blacks set up an alternative economic or political power structure in response to the injustice. Marcus Garvey saw it this way:

Negro newspapers in one breath will publish and make big display of lynchings, mob-violences, riots, injustices perpetrated and heaped upon the race, and denounce them with the most heated ferocity and point out the hopelessness of the race in the midst of its environments, yet in the same issues in another breath denounce most vehemently the plan of nationalism for the race in Africa and attempt to crucify me for advocating it as a solution of the problem. Who are these newspapermen fooling?

In effect, the Black press had allowed itself to become a junior partner in the white business world, a world that depends on Black consumerist dependency for its financial survival. The negro press, in turn, depends on the white advertising dollars—and that dependency soon overcame any fidelity to a Black movement ideology.

In the very first issue of Ebony magazine in November 1945—the one with a cover photo of 7 boys, 6 of them white, 1 an Eastern Indian—publisher John Johnson made his mission very clear:

“We’re rather jolly folks, we Ebony editors. We like to look at the zesty side of life. Sure, you can get all hot and bothered about the race question (and don’t think we don’t) but not enough is said about all the swell things we Negroes can do and will accomplish.”

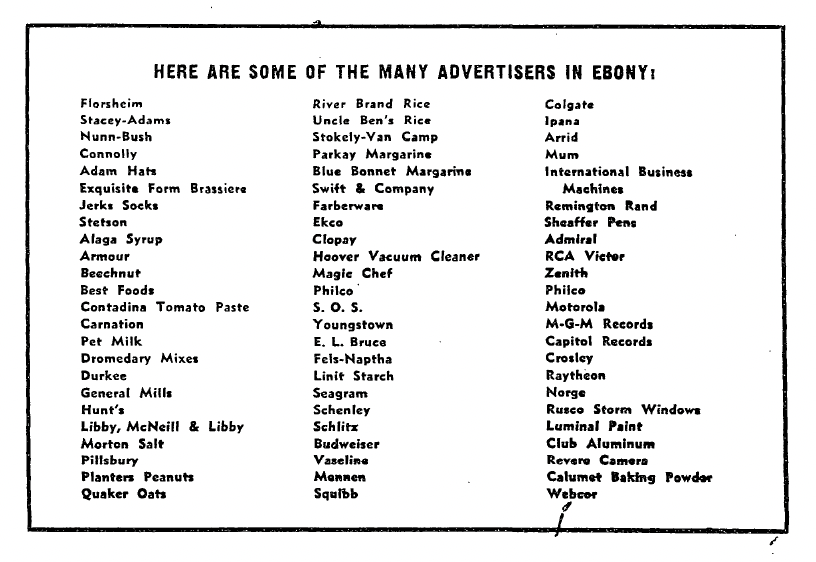

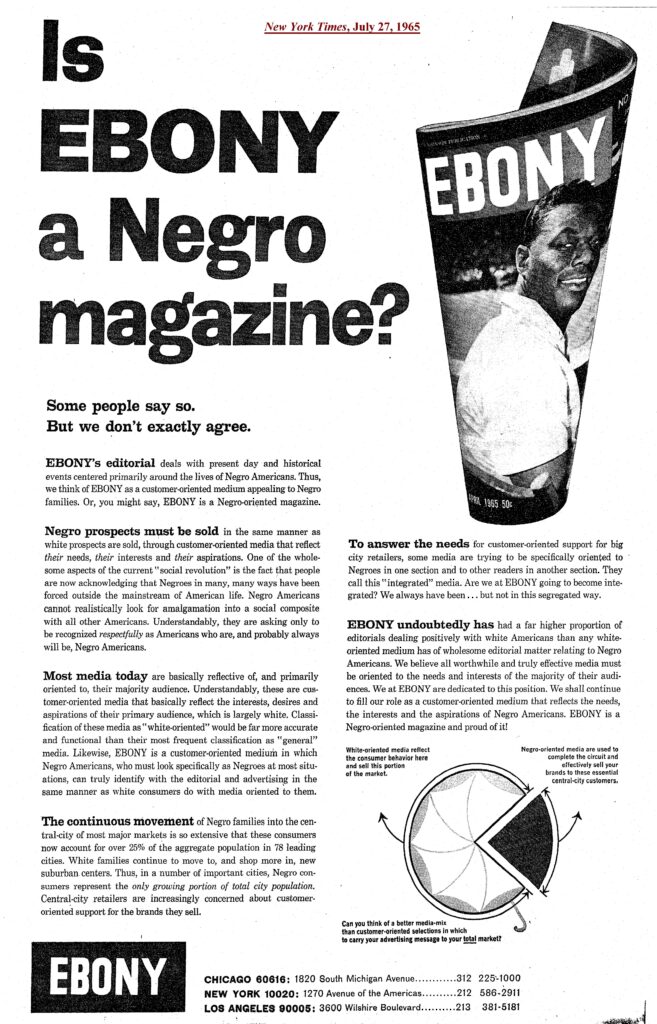

Twenty years later Ebony further clarified its role in the era of Black Power, when it took out a full-page ad in the New York Times with the bold headline “Is EBONY a Negro magazine? Some people say so. But we don’t exactly agree.” The ad appeared in other publications that targeted white advertisers, including Advertising Age, Printer’s Ink, Media/Scope, and Women’s Wear Daily, demonstrating that its role in the Black struggle was

(1) non-existent;

(2) apolitical and non-controversial; and, therefore,

(3) a perfect vehicle, according to the ad, for white “big city retailers” to exploit the “increased income of Negroes.”

Around this same time an examination of one Ebony issue found that twenty percent of its revenue came from ads for “products which will remove or modify Negroid characteristics.”

Around this same time an examination of one Ebony issue found that twenty percent of its revenue came from ads for “products which will remove or modify Negroid characteristics.”

Ebony has come a long way from that early self-definition to a more forceful forum for today’s Black issues. But others have been content to specialize in the coverage of negro events, where the bejeweled elite imitate the conventions of high-class whites and gush over their excesses. It cheered the closeness of a negro clerk to the white city-hall sovereigns and trumpeted the latest white-published “must-read” negro literature. Its social responsibility revolves mostly around notifying Blacks of the next television drama or Hollywood movie in which a favorite negro celebrity will appear, or of the latest ghetto bargain.

But most important, the Black media simply alerts the Black masses to which Euro-retailer will sell them below-quality groceries and trinkets at monopolistic prices. The Black press, having lost its revolutionary initiative, also eventually lost its Black readership.

By 1980, Black newspapermen were publicly advocating total surrender. Having backed the wrong horse (integrationism) and ridden it long after its death, they found their milquetoast posture on racial affairs being abandoned by their revolutionary-minded Black readers and neglected by the middle-class-bound integrationist negroes, who, according to one observer, “have given up these papers along with other memories they preferred to forget.” Strengthening their voices on Black issues didn’t seem to occur to the Black publishers. The Chicago Defender’s John Sengstacke went before the National Newspaper Publishers Association, over which he presided, to advocate a “drastic” measure that Blacks had assumed was already standard operating procedure: “We ought to take into serious consideration integration on the social and economic spheres.”

The “wait-and-see-what-white-folks-say” political posture of the newspaper establishment has made the Black press largely irrelevant to any significant Black grassroots movement. Editorially, little has changed since Garvey’s 1923 pronouncement: “the Black press still decries the abuses of white society, yet it still encourages the Black masses to ‘go ’head on and integrate.’”

And little has changed since Roi Ottley’s 1943 observation that the ads in the Black newspapers “consist largely of sucker items, such as lodestones, zodiacal incense, books on unusual love practices, and products that purport to turn black skin to white or straighten kinky hair.” Today’s ads are still for suckers: Army, Navy and Air Force recruitment, nicotine and alcohol pushers, 900-line “psychics,” “dating” services, and, oh yes, products that purport to turn black skin to white or straighten kinky hair.

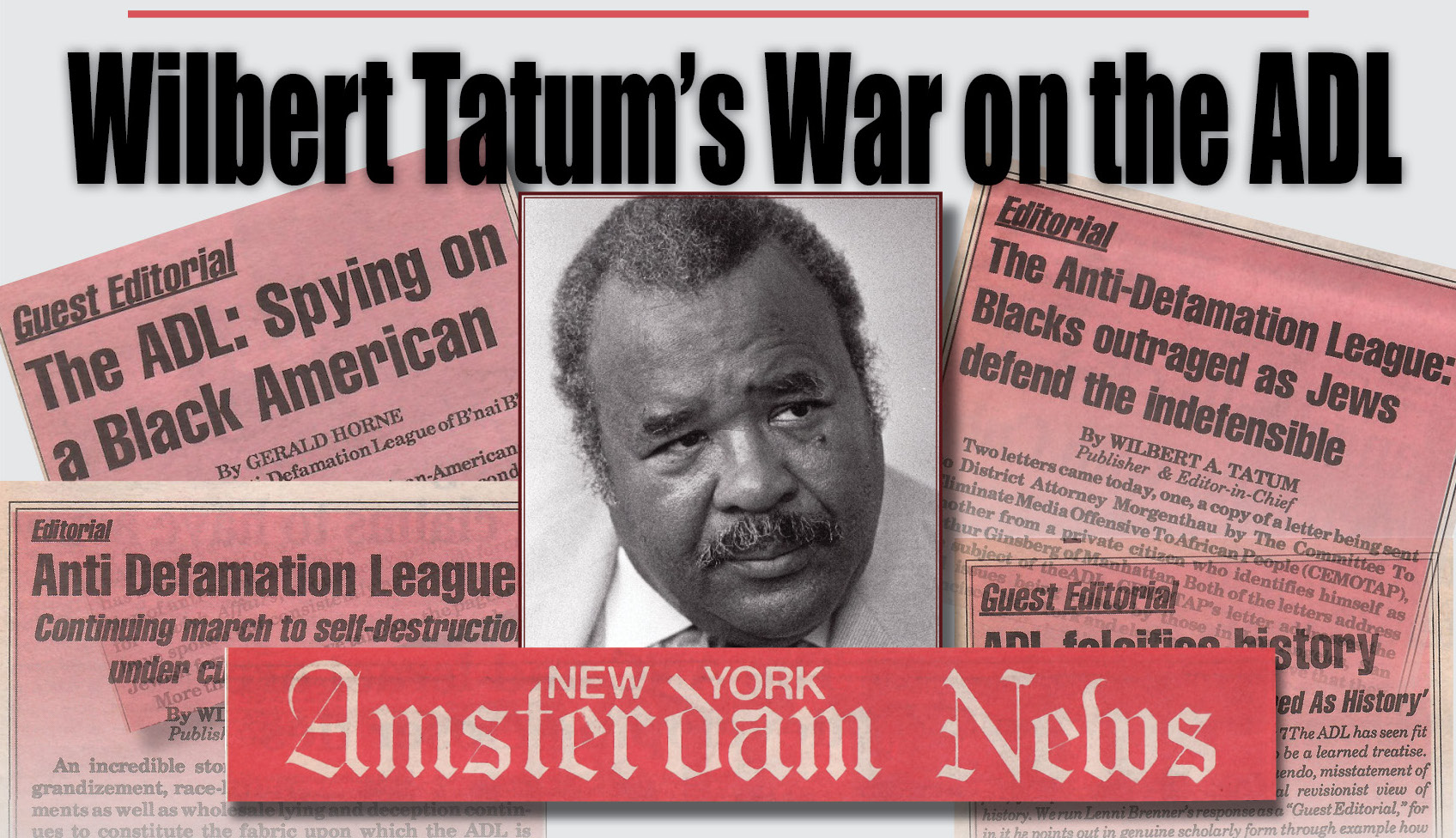

See also Wilbert Tatum’s War on the ADL