THE BLACK PRESENCE IN AMERICA BEFORE COLUMBUS

by The African United Front © 2016

“The African presence is proven by stone heads, terra cottas, skeletons, artifacts, techniques and inscriptions, by oral traditions and documented history, by botanical, linguistic and cultural data. When the feasibility of African crossings of the Atlantic was not proven and the archaeological evidence undated and unknown, we could in all innocence ignore the most startling of coincidences. This is no longer possible. The case for African contacts with pre-Columbian America, in spite of a number of understandable gaps and a few minor elements of contestable data, is no longer based on the fanciful conjecture and speculation of romantics. It is grounded now upon an overwhelming and growing body of reliable witnesses.” –Ivan Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus.

On September 24th, 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in Washington, D.C. The New York Times has stated that this long awaited monument to centuries of African American suffering and triumphs “makes a powerful declaration: The African-American story is a central part of the American story.”

On September 24th, 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in Washington, D.C. The New York Times has stated that this long awaited monument to centuries of African American suffering and triumphs “makes a powerful declaration: The African-American story is a central part of the American story.”

How central the role was that African Americans played has never been completely told and, unfortunately, a pivotal part of that history has been excluded from this exhibit. In truth, Africans began coming to the Americas thousands of years before Columbus; and the evidence of their presence, though systematically ignored by mainstream scholars, is overwhelming and undeniable. As Columbus Day (October 12) approaches and as we celebrate the 40th anniversary of the publication of They Came Before Columbus by the late Rutgers University professor, Ivan Van Sertima, we must reveal to the world the grandeur of Africa by highlighting the achievements of some of its great navigators and rulers.

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS

Ever since Christopher Columbus first suggested that Black Africans preceded him to the New World, a number of scholars have investigated this contention. In his Journal of the Second Voyage, Columbus wrote that when he reached Haiti, then labeled Espanola, the native people told him that black skinned people had come from the south and southeast in ships trading in gold tipped metal spears. The following is recorded in Raccolta, part I, volume I:

“Columbus wanted to find out what the Indians of Espanola had told him, that had come from the south and southeast, [N]egro people who brought those spear points made of a metal which they call guanin, of which he had sent samples to the king and queen for assay and which was found to have 32 parts – 18 of gold, 6 of silver, and 8 of copper.”1

Curious about the validity of this story, Columbus did indeed send samples of these spears back on a mail ship to Spain to be examined, and it was found that the ratio of properties of gold, copper, and silver alloy were identical to the spears then being forged in African Guinea.2

In a book on the life of Columbus, his son, Ferdinand, reported that his father saw Black people himself when he reached the region just north of the country today called Honduras. Nearly a dozen other European explorers also found Black people in the Americas when they reached the Western Hemisphere. In September 1513, Vasco Nunez de Balboa led his men down the slopes of Quarequa, which was near Darien, now called Panama, where they saw several Black men, who were captured by native Americans.3 “Balboa asked the Indians whence they got them [the Black people], but they could not tell, nor did they know more than this, that men of this color were living nearby and they were constantly waging war with them. These were the first Negroes that had been seen in the Indies.”4 Peter Martyr, the first prominent European historian of the New World, stated that the Black men seen by Balboa and his companions were shipwrecked Africans who had taken refuge in the local mountains.5

Father Fray Gregoria Garcia, a priest of the Dominican order who spent nine years in Peru during the early sixteenth century, identified an island off of Cartagena, Columbia as the place where the Spanish first found Black people in the New World. As in Darien, these Africans were also captives of war among the native Americans.6 Also during the sixteenth century – after the advent of Columbus, but before the universal enslavement of Africans – Cabello de Balboa cited a group of seventeen Black people who, after being shipwrecked in Ecuador, became governors of an entire province of native Americans.7

TESTIMONY IN STONE

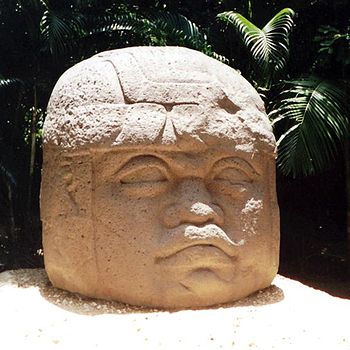

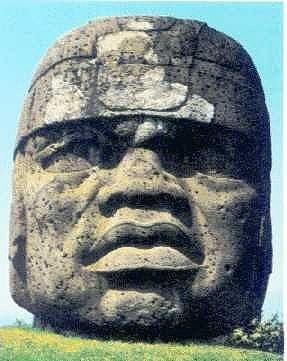

Although eyewitness accounts of early European explorers may be the best evidence of an African presence in the New World that preceded Columbus, it is certainly not the only evidence. “As early as the nineteenth century” wrote Jonathan Leonard, a specialist on early Mexico, “reports had come from this coastal region [the Mexican gulf coast] of gigantic heads with Negroid features.”8 The first of these heads was discovered by Jose Melgar in Veracruz in 1862. He wrote two articles about this particular head, one in the Boletin de Geografia y Estadistica, and the other in the respected Sociedad Mexicana de Geografia y Estadistica. “Melgar’s mind,” wrote art historian Alexander von Wuthenau,

“not yet tainted by certain currents of modern (and perhaps not so modern) anthropology, reacted quite normally to this newly found evidence of [the] black man’s presence in ancient America. He furthermore cites a document of Francisco Nunez Vega (1691), who describes an ancient calendar found in Chiapas that mentions seven ‘negritos’ representing the seven planets.”9

In describing the Olmec head, Melgar wrote that “what astonished me was the Ethiopic [Black African] type which it represents. I reflected that there had undoubtedly been Blacks in this country and this had been in the first epoch of the world…”10  Since Melgar’s discovery sixteen other colossal stone heads have been found in many parts of Mexico, including ancient sacred sites such as La Venta and Tres Zapotes in southern Mexico. Ranging up to 11.15 feet in height and weighing 30 to 40 tons, these statues generally depict helmeted Black men with large eyes, broad fleshy noses and full lips.

Since Melgar’s discovery sixteen other colossal stone heads have been found in many parts of Mexico, including ancient sacred sites such as La Venta and Tres Zapotes in southern Mexico. Ranging up to 11.15 feet in height and weighing 30 to 40 tons, these statues generally depict helmeted Black men with large eyes, broad fleshy noses and full lips.

They appear to represent priest-kings who ruled vast territories in Mesoamerica [Mexico and Central America] during the Olmec period, which is to be considered later herein. On the strength of the colossal Olmec heads and other evidence, several early Mexican scholars concurred with Melgar’s contention that Black people settled the New World, particularly Mexico, in antiquity. “In a very ancient epoch,” wrote historian Riva Palacio, “or before the existence of the Otomies [native Americans] or better yet invading them, the Black race occupied our territory… This race brought its religious ideas and its own cult.”11

Author C.C. Marquez, adds that “[s]everal isolated but concordant facts permit the conjecture that before the formation and development of the three great ethnographic groups…a great part of Amcerica was occupied by [the] Negroid type.”12

Historian Nicholas Leon was of a similar opinion:

“The oldest inhabitants of Mexico, according to some, were Negroes, and according to others, the Otomies. The existence of Negroes and giants is commonly believed by nearly all the races of our soil… Several archaeological objects found in various locations demonstrate their existence… Memories of them in the most ancient traditions induce us to believe that the Negroes were the first inhabitants of Mexico”13

Another authority, J.A. Villacorta, has written: “Any way you view it, Mexican civilization had its origin in Africa.”14 Finally, historian Orozco y Berra declared in his History of the Conquest of Mexico, that there was, unquestionably, a significant, ongoing, and intimate pre-Columbian relationship between Mexicans and Africans.15

In addition to Mexican scholars, a number of others have described the colossal stone heads in terms similar to those of Melgar. Chief among them was the American Olmec specialist Matthew Stirling. He wrote:

“Cleared of the surrounding earth, it [the colossal head] presented an awe-inspiring spectacle. Despite its great size, the workmanship is delicate and sure, its proportions perfect… The features are bold and amazingly negroid in character.”16

Another authority, Selden Rodman speaks of the “…colossal ‘Negroid’ heads…”17 European journalist and Olmec specialist, Walter Hanf, describes “carved colossal heads with Negroid features, deformed and close-shaven skulls, blunt noses, and protruding lips.”18 Author and anthropologist Sharon McKern states that the colossal heads are “inescapably Negroid.”19

Historian Nicholas Cheetham writes of the “exaggeratedly Negroid features” of the stone heads.20 Finally, another scholar, Floyd Hayes, has provided the following thought provoking assessment of the racial significance of the colossal stone heads:

“One might merely ask himself: if Africans were not present in the Americas before Columbus, why the typically African physiognomy on the monuments? It is in contradiction to the most elementary logic and to all artistic experience to suggest that these ancient Olmec artists could have depicted, with such detail, African facial features they had never seen.”21

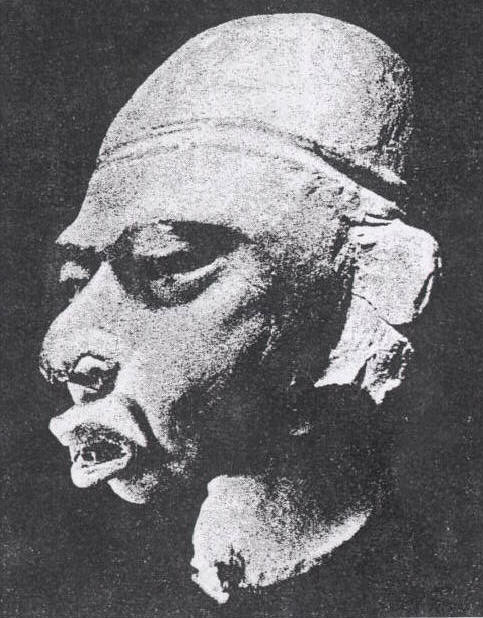

FIGURINES IN CLAY

According to Von Wuthenau, “[t]he startling fact is that in all parts of Mexico, from Campeche in the east to the southeast of Guerrero, and from Chiapas, next to the Guatemalan border, to the Panuco River in the Huasteca region (north of Veracruz) archeological pieces representing Negro or Negroid people have been found, especially in archaic or pre-classic sites. This also holds true for large sections of Mesoamerica and far into South America – Panama, Columbia, Ecuador, and Peru…”22 For years the Diego Rivera Museum of Mexico housed the Alexander von Wuthenau Collection of remarkable figurines depicting Black priests, chiefs, dancers, wrestlers, drummers, and others across the social spectrum. An examination of this artwork, wrote Van Sertima,

“reveals the unmistakable combination of the kinky hair, broad nose, generous lips, frequency of prognathism (projecting jaws), occasional goatee beard, and sometimes distinctly African ear pendants, hairstyles, tattoo markings, and coloration.”23

SKULLS AND SKELETONS

Author David Imhotep cites a number of scientists and scholars who have identified prehistoric skulls and skeletons of Black people of the Austro-Negrito type, dating back to as early as 56,000 years ago, throughout the New World.24 This appears to be substantiated by more recent discoveries.25

Our focus here, however, is on the Negroid skulls and skeletons that have been discovered at ancient and medieval New World sites. One of the world’s most renowned craniologists, Polish professor Andrzej Wiercinski, revealed to the 41st Congress of Americanists in Mexico in September 1974, that African skulls had been discovered at Olmec sites in Tlatilco, Cerro de las Mesas and Monte Alban. In using standard scientific measurements of skull shape and the formation of the face, Wiercinski found “a clear prevalence of the total Negroid pattern…”26

In this same vein, historian Frederick Peterson has written that “[w]e can trace the progress of man in Mexico without noting any definite Old World influence during this period (1000-650 B.C.) except a strong Negroid substratum connected with the Magicians [Olmecs].”27 Finally, in February of 1975, a team from the Smithsonian Institute reported the discovery of two Negroid male skeletons in a grave in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Scientific analysis of the surrounding soil suggests that the skeletons date back to about 1250 A.D.28

THE OLMECS

Any objective analysis of the evidence clearly shows that Black people reached the Americas thousands of years before Columbus. But, in the words of Van Sertima, “proof of contact is only half of the story. What is the significance of this meeting of Africans and Native Americans? What cultural impact did the outsiders have on American civilization?”29 It would appear that the impact of the African explorers on the New World as a whole was widespread, profound and enduring. In this summary, however, we are confining ourselves to “a particular geographic region (the Gulf of Mexico), a particular culture complex or civilization (known as Olmecs), and a particular period of history (948-680 B.C.)”.30

The name Olmec means “Dweller in the land of Rubber” and could technically be applied to anyone who lived in the jungle areas of the Mexican Gulf Coast in antiquity.31 For centuries the indigenous people there created and perpetuated a local culture that varied little from its surroundings. Then, suddenly, sometime after the first millennium B.C., this region became the center of a full-blown civilization that had no detectable antecedents. This high culture is now known as the Olmec civilization. According to Michael Coe, the world’s foremost authority on Olmec culture, “There is not the slightest doubt that all later civilizations in Mesoamerica, whether Mexican or Mayan, rest ultimately on an Olmec base.”32 Van Sertima adds: “The Olmec civilization was formative and seminal: it was to touch all others on this continent, directly or indirectly.”33

Olmec monument from Tres Zapotes, Mexico (c. 1100 B.C.)

Some of the Olmec sculptures depicting human beings are so decidedly Negroid that many scholars long thought that the indigenous Olmec culture itself was of Black origin. The original Olmecs were Native Americans who were very probably colonized and acculturated by Africans who settled their homeland. “…I have never claimed,” writes Van Sertima, “that Africans created or founded the Olmec civilization…They left a significant influence upon it…and that is more than can be said of any other Old World group visiting the native American or emigrating to the continent before Columbus.”34

A study of the Olmec civilization reveals elements that are remarkably similar to the ritual traits and techniques in the Egypto-Nubian world of the same period. When viewed in their totality these cultural similarities strongly suggest that there was contact between the ancient Africans from the Nile Valley and the Olmec people. Conspicuous among these shared elements are those adopted by the monarchies in both civilizations, “and appear in a combination too arbitrary and unique to be independently duplicated.”35 They include the following: The double crown, the royal flail, the sacred boat or ceremonial bark of the kings, the religious value of the color purple and its special use among priests and people of high rank; the artificial beard, feathered fans and the parasol or ceremonial umbrella. In an oral tradition recorded in the Titulo Coyoi, a major document of the Maya, the parasol is specifically mentioned as having been brought to the New World by foreigners who traveled by sea from the east.36

The Indian scholar, Rafique Jairazbhoy, has studied the ancient Egyptians and the Olmecs in great detail and has pointed to many other ritual parallels between the two groups. For example, there are hand-shaped incense spoons found in Olmec sites that are almost identical to their Eyptian counterparts and have similar names. In Egypt there are numerous sculptures depicting four figurines symbolically holding up the sky. A similar sculpture has been discovered at the Olmec site of Portrero Nuevo. In Egyptian mythology the human headed bird, Ba, flies out of the tomb. A bird with a human head also appears in a relief from Izapa, Mexico;37 “and Mexican sarcophagi leave an opening in the tomb as do the Egyptians, for the bird’s escape from the dead.”38

Jairazbhoy also shows remarkable similarities between several gods in the Egyptian underworld and those of Olmec Mexico. The most striking similarities between the two cultures are seen in the magnificent stone structures that have been found on both sides of the Atlantic. In America we have no antecedents for the construction of pyramids, for example, “whereas there is a clear series of evolving steps and stages [in pyramid building] in the Egypto-Nubian world.”39

Van Sertima asks, “Where do the first miniature step pyramid and the first manmade mountain or conical pyramid appear in America? On the very ceremonial court and platform where four of the African-type heads were found in the holy capital of the Olmec world, La Venta. Even among the Maya, where Dr. Hammond has found 2000 B.C. villages, no pyramid appears until much later.”40

While we could continue to cite infinite similarities between ancient African and New World cultures in various fields including linguistics and botany, let us turn instead to consider the likely origin of the Africans who appear to have reached and profoundly influenced American culture thousands of years before Columbus. The currents off Africa serve as veritable conveyor belts to the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and the northeastern corner of South America. Mayan and African oral traditions speak of pre-Columbian expeditions across the Atlantic from east to west;41 and the modern explorer, Thor Heyerdahl, has demonstrated that ships modeled after the ancient Egyptian papyrus boat could indeed successfully make such a journey.42 Other Africans also built sturdy, seaworthy ships.43

CONCLUSION

Who, then, were the Africans who sailed to America in antiquity? Jairazbhoy believes that the earliest settlers were ancient Egyptians led by King Ramesis III, during the nineteenth dynasty.44 Van Sertima contends that “a small but significant number of men and a few women, in a fleet protected by a military force, moved west down the Mediterranean toward North Africa in the period 948-680 B.C…and got caught in the pull of one of the westward currents off the North African coast, either through storm or navigational error,” and were carried across the Atlantic to the New World. In his view this fleet was probably led by Phoenician navigators who had been pressed into service by the Nubian pharaohs of Egypt during the twenty fifth dynasty.45

Other scholars contend that numerous navigators sailed to the Americas from West Africa when the medieval empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhay flourished in that region.46 In light of the vast evidence available (far more, for example, than that of the Vikings) of an African presence in ancient America, why is this information virtually unknown to the general public? Speaking specifically about the African influence on the Olmec culture, historian Zecharia Sitchin provides this view:

In light of the vast evidence available (far more, for example, than that of the Vikings) of an African presence in ancient America, why is this information virtually unknown to the general public? Speaking specifically about the African influence on the Olmec culture, historian Zecharia Sitchin provides this view:

“It is an embarrassing enigma, because it challenges scholars and prideful nationalists to explain how people from Africa could have come to the New World not hundreds but thousands of years before Columbus, and how they could have developed, seemingly overnight, the Mother Civilization of Mesoamerica. To acknowledge the Olmecs and their civilization as the Mother Civilization of Mesoamerica means to acknowledge that they preceded that of the Mayans and Aztecs, whose heritage the Spaniards tried to eradicate and Mexicans today are proud of.”47

In a world accustomed to suppressing, distorting, ignoring or denying the achievements of Black Africans it is difficult to accept the historical paradigm shift mandated by the evidence presented here. For, whether we accept the facts or not, Jairazbhoy appears to have been right when he wrote: “The black began his career in America not as slave but as master.”48

END NOTES

- Ivan Van Sertima, “Evidence For An African Presence in Pre-Columbian America,” in Ivan Van Sertima (ed.) African Presence in Early America, New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1992, p.30.

- Ibid.

- Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus, New York, Random House, 1976, p.19-23.

- Lopez de Gomara, Historia de Mexico, Anvers, 1554.

- A. MacNutt (ed and trans.), De Orbo Novo: The Eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera, New York, 1912.

- Alexander von Wuthenau, The Art of the Terracotta Pottery in Pre-Columbian South and Central America, New York, Crown Publishers, 1969, p.167.

- Stephen Jett in Riley, Kelley, Pennington and Rands (eds.), Man Across the Sea, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1971, p.16.

- N. Leonard, Ancient America, New York, Time Incorporated, 1967, p.32.

- Alexander von Wuthenau, Unexpected Faces in Ancient America: The Historical Testimony of Precolumbian Artists – 1500 B.C. to 500 A.D., New York, Crown Publishers Inc., 1975, p.77. Also see J. Melgar, “Notable Escultural Antiqua, Antiguedades Mexicanos”, Boletin de Geografia y Estadistica, Seunda Epoca, pp.292-297, 1869 and “Estudio Sobra la Antiguedad y el Origen de la Cabeza Colosal de tipo Ethiopico que Esiste en Huey a pan”, Boletin de la Sociadad. Mexicana, 3, pp.104-109, 1871.

- Boletin de Geografia y Estadistica, op. cit., pp.292-297.

- Palacia, Mexico a Traves de los Siglos, translated by M. Lumumba, Ballesca y Comp., Editores, Mexico, p.13, 1889.

- Carlos C. Marquez, Prehistoria v. Viajes, San Augustin, p.137-138, 1893.

- Quoted in J.A. Rogers, Sex and Race, New York, published by the author, 1942, vol. 1, p.270.

- Jose A. Villacorta, Arqueologia guatemalteca (Guatemala, C.A.: Tipografia nacional, 1930), p.336; also see Prehistoria and Historia antigua de Guatemalteca (Guatemala C.A., Tipografia nacional, 1938), pp. 222-239.

- Orozco y Berra, Historia Antiqua y de la Conquista de Mexico, Mexico, 1880, vol. 1. P.109.

- Matthew M. Stirling, “Discovering the New World: Oldest Dated Work of Man,” National Geographic Magazine, vol.76 (August, 1939), pp.183-218.

- Selden Rodman, The Mexico Traveler, New York, Meredith Press, 1969, p.6.

- Walter Hanf, Mexico, Chicago, Rand McNally & Company, 1967, p.19.

- Sharon S. McKern, Exploring the Unknown, Mysteries in American Archeology, New York, Praegan Publishers, 1972, p.104.

- Nicholas Cheetham, Mexico, A Short History, New York, Thomas Y. Crowell, 1970, p.19.

- W. Hayes III, “The African Presence in America Before Columbus,” The Black World, July, 1973, p.13.

- Von Wuthenau, op. cit., p.965.

- Van Sertima, “Evidence For An African Presence in Pre-Columbian America,” op. cit., p.37.

- David Imhotep, Ph.D, The First Americans Were Africans: Documented Evidence, United States, AuthorHouse, 2011.

- http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/3774/did-australian-aborigines-reach-america-first.

- Proceedings of the Forty First International Congress of Americanists, 1974, pp.116-126.

- Frederick Peterson, Ancient Mexico, New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1959, p.50.

- Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus, cit., p.31.

- Ivan Van Sertima, “Egypto-Nubian Presences in Ancient America,” in Ivan Van Sertima’s (ed.) African Presence in Early America, New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1992, p.71.

- Ibid , p.55.

- Ignacio Bernal, The Olmec World, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1969. P.11.

- Michael Coe, Mexico, New York, Praeger Publishers, 1962, p.88.

- Van Sertima, “Egypto-Nubian Presences in Ancient America,” op. cit., p.65.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p.72.

- A. Jairazbhoy, Ancient Egyptians and Chinese in America, New Jersey, Rowman and Littlefield, 1974, p.8.

- Van Sertima, “Egypto-Nubian Presences in Ancient Mexico,” pp.73-75.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp.75-76.

- Ibid.

- Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus, op. cit. pp.35-49 and 265.

- Van Sertima, “Egypto-Nubian Presences in Ancient Mexico,” p.70.

- Michael Bradley, Dawn Voyage, The African Discovery of America, New York, A&B Book Publishers, 1992, pp.92-133.

- Jairazbhoy, op. cit.

- Van Sertima, “Egypto-Nubian Presences in Ancient Mexico,” op. cit.

- Bradley, op. cit. Also see Leo Weiner, Africa and the Discovery of America, Philadelphia, Innes and Sons, 1920-22, vols. 1-3. Harold Lawrence, “African Explorers in the New World, The Crisis, June-July 1962, pp.321-332. Heritage Program Reprint, p.11.

- Zecharia Sitchin, The Earth Chronicles Expedition, Journey to the Mythical Past, Rochester Vermont, Bear & Company, 2004, p.66.

- Jairazbhoy, op. cit.