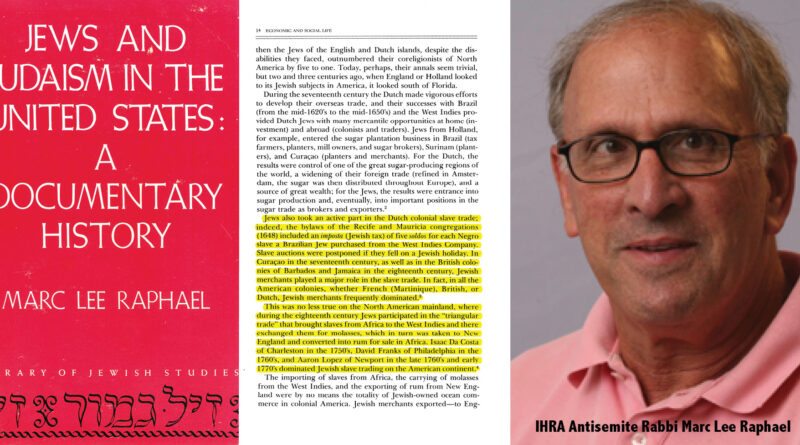

Rabbi Marc Lee Raphael on Jews & the Slave Trade

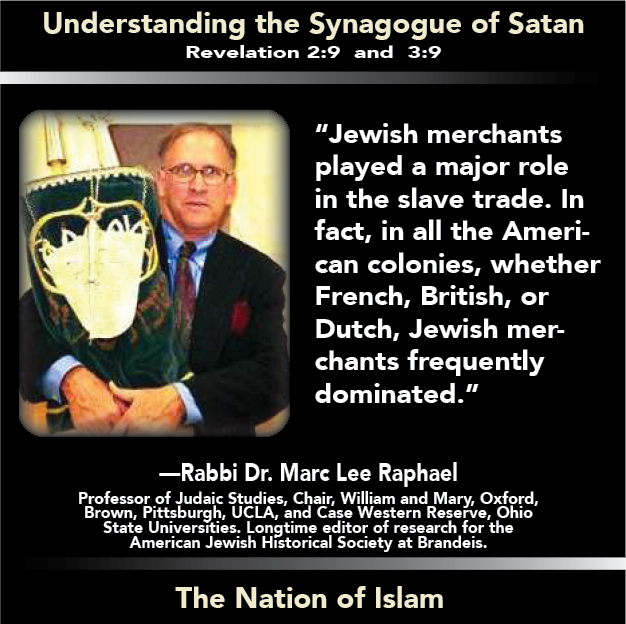

Rabbi Marc Lee Raphael: Nathan and Sophia Gumenick Professor of Judaic Studies, Professor of Religion, and Chair, Department of Religion, The College of William and Mary, and a Visiting Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford University. He has been the editor of the quarterly journal, American Jewish History, for 19 years, and a visiting professor at Brown University, the University of Pittsburgh, HUC-JIR, UCLA, and Case Western Reserve University. He came to The College of William and Mary in 1989 after 20 years at Ohio State University. He is the author of many books on Jews and Judaism in America, and his most recent publication (with his wife Linda Schermer Raphael) is When Night Fell: An Anthology of Holocaust Short Stories (Rutgers University Press, 1999). He is now writing Judaism in America for the Contemporary American Series of Columbia University Press.

The following passages are from Dr. Raphael’s book Jews and Judaism in the United States: A Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1983), pp. 14, 23-25.

“This was no less true on the North American mainland, where during the eighteenth century Jews participated in the ‘triangular trade’ that brought slaves from Africa to the West Indies and there exchanged them for molasses, which in turn was taken to New England and converted into rum for sale in Africa. Isaac Da Costa of Charleston in the 1750’s, David Franks of Philadelphia in the 1760’s, and Aaron Lopez of Newport in the late 1760’s and early 1770’s dominated Jewish slave trading on the American continent.”

Dr. Raphael discusses the central role of the Jews in the New World commerce and the African slave trade (pp. 23-25):

Groups of Jews began to arrive in Surinam in the middle of the seventeenth century, after the Portuguese regained control of northern Brazil. By 1694, twenty-seven years after the British had surrendered Surinam to the Dutch, there were about 100 Jewish families and fifty single Jews there, or about 570 persons. They possessed more than forty estates and 9,000 slaves, contributed 25,905 pounds of sugar as a gift for the building of a hospital, and carried on an active trade with Newport and other colonial ports. By 1730, Jews owned 115 plantations and were a large part of a sugar export business which sent out 21,680,000 pounds of sugar to European and New World markets in 1730 alone.

Slave trading was a major feature of Jewish economic life in Surinam, which [w]as a major stopping-off point in the triangular trade. Both North American and Caribbean Jews played a key role in this commerce: records of a slave sale in 1707 reveal that the ten largest Jewish purchasers (10,400 guilders) spent more than 25 percent of the total funds (38,605 guilders) exchanged.

Jewish economic life in the Dutch West Indies, as in the North American colonies, consisted primarily of mercantile communities, with large inequities in the distribution of wealth. Most Jews were shopkeepers, middlemen, or petty merchants who received encouragement and support from Dutch authorities. In Curacao, for example, Jewish communal life began after the Portuguese victory in 1654. In 1656 the community founded a congregation, and in the early 1670’s brought its first rabbi to the island. Curacao, with its large natural harbor, was the steppng-stone to the other Caribbean islands and thus ideally suited geographically for commerce. The Jews were the recipients of favorable charters containing generous economic privileges granted by the Dutch West Indies Company in Amsterdam. The economic life of the Jewish community of Curacao revolved around ownership of sugar plantations and marketing of sugar, the importing of manufactured goods, and a heavy involvement in the slave trade; within a decade of their arrival, Jews owned 80 percent of the Curacao plantations. The strength of the Jewish trade lay in connections in Western Europe as well as ownership of the ships used in commerce. While Jews carried on an active trade with French and English colonies in the Caribbean, their principal market was the Spanish Main (today Venezuela and Colombia).

Extant tax lists give us a glimpse of their dominance. Of the eighteen wealthiest Jews in the 1702 and 1707 tax lists, nine either owned a ship or had at least a share in a vessel. By 1721 a letter to the Amsterdam Jewish community claimed that “nearly all the navigation…was in the hands of the Jews.” Yet another indication of the economic success of Curacao’s Jews is the fact that in 1707 the island’s 377 residents were assessed by the Governor and his Council a total of 4,002 pesos; 104 Jews, or 27.6 percent of the taxpayers, contributed 1,380 pesos, or 34.5 percent of the entire amount assessed.

In the British West Indies, two 1680 tax lists survive, both from Barbados; they, too, provide useful information about Jewish economic life. In Bridgetown itself, out of a total of 404 households, 54 households or 300 persons were Jewish, 240 of them living in “ye Towne of S. Michael ye Bridge Town.” Contrary to most impressions, “many, indeed, most of them, were very poor.” There were only a few planters, and most Jews were not naturalized or endenizened (and thus could not import goods or pursue debtors in court). But for merchants holding letters of endenization, opportunities were not lacking. Barbados sugar—and its by-products rum and molasses—were in great demand, and in addition to playing a role in its export, Jewish merchants were active in the import trade. Forty-five Jewish households were taxed in Barbados in 1680, and more than half of them contributed only 11.7 percent of the total sum raised. While the richest five gave almost half the Jewish total, they were but 11.1 percent of the taxable population. The tax list of 1679-80 shows a similar picture; of fifty-one householders, nineteen (37.2 percent) gave less than one-tenth of the total, while the four richest merchants gave almost one-third of the total.

An interesting record of interisland trade involving a Jewish merchant and the islands of Barbados and Curacao comes from correspondence of 1656. It reminds us that sometimes the commercial trips were not well planned and that Jewish captains—who frequently acted as commercial agents as well—would decide where to sell their cargo, at what price, and what goods to bring back on the return trip.

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.

^^