New York & the Fight for Black Education

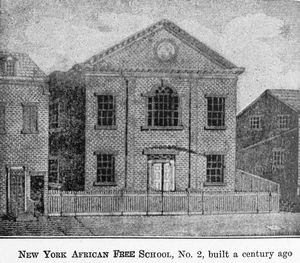

The New York African Free School was founded in 1786, established by the New York Manumission Society to divert Black children from “the slippery paths of vice” and to make them “quiet and orderly citizens.” Even the Society’s abolitionist leader, John Jay, had low expectations of his pitiable Black clients. To an associate he wrote:

As to the eventual fate of the children, it is important that they be not left entirely either to their parents or to themselves, it being difficult to give them morals, manners, and habits. These can only be learned from reality.

The school had no intention of making Black children into doctors, engineers or scientists; instead the school’s intent was to make them “more orderly and tractable as they emerged from slavery.” After a suitable amount of training, “graduates” were bound out as sailors, apprentices, and domestic servants.

Nonetheless, the African Free School became central to the Black New Yorker’s training process. Black students demonstrated a thirst for knowledge and a discipline that was reflected in this observation in the Commercial Advertiser: “We never beheld a white school of the same age, (of and under fifteen), in which, without exception, there was more order and neatness of dress, and cleanliness of person.” The article further pointed out that of the 700 pupils, 264 were capable of reading.

Soon, Black New Yorkers directly challenged the aims of the school as inadequate. In the late 1820s, in a foreshadowing of the school battles of the 1960s, Black community leaders demanded a say in determining the educational policies at the African Free Schools and initiated a boycott.

The white man that ran the schools, Charles Andrews, was pressured to resign in 1832 when it was learned that he had developed the opinion that Blacks ought to go back to Africa. White school administrators explained that his departure was the result of “prejudice now existing against him in the black community.”

Blacks insisted that Black men and women teach their children. James Adams, a Black man, replaced Andrews and attendance at the African Free Schools climbed above 500 for the first time.

The Manumission Society countered such boldness by transferring its schools to the Public School Society, which made sweeping changes without consulting the Black community leaders, parents or students. Most of the Black teachers were discharged by the new trustees, among other changes resented by Blacks. They vigorously protested and their Black teachers were reappointed, and enrollments began to improve.

By 1834 seven African schools had been established throughout the city. Other efforts produced at least 74 Black schools throughout the state.

In Rochester, there were no legal barriers against the enrollment of Blacks in the school system. In 1834, however, the school committee found that “the colored scholar can hardly prosper.” It stated plainly that “his mind is in chains, and he is a slave.” Local parents successfully petitioned to form an African School.

Buffalo Blacks sent their children to sit-in at local schools, but the school officials physically forced them out. State Superintendent John Spencer concurred with the schools’ approach to keeping Black children out of the local schools. “The admissions of colored children,” he said, “is in many places so odious that whites will not attend.” Alderman O. G. Steele demanded that Blacks be ejected from public schools:

They [the blacks] must be looked upon with aversion and treated with more or less opprobrium and their progress in their studies must be retarded rather than advanced in the public schools.

In 1848, Buffalo School Superintendent Samuel Caldwell physically ejected Black children from the public schools. Drawing on his Hamitic training, he reasoned that

“[t]hey require…longer training and severer discipline…and generations must elapse before they will possess the vigor of intellect, the power of memory and judgment, that are so early developed in the Anglo-Saxon race.”

Strong Black leaders were frustrated by the imposition of “moderate” uncle toms as spokespersons for the Buffalo community—a tactic still in widespread and successful use today. White officials used the hand-crafted division to “cite the difference of opinion among the colored people” as the reason for refusing to change their policies.

Superintendent of Schools John S. Fosdick provides a good example of the kind of white friends Blacks were “blessed” with in New York. A “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, Fosdick described integrationist Blacks as “mischievous agitators,” and diligently sought to enforce Section 5 of Buffalo’s 1853 Charter, which stated that “all public schools organized in the city of Buffalo shall be free to all white children.” Blacks, seeking education for their children, defied the ban on their school attendance and the outraged Fosdick moved into action by physically expelling Blacks from the schools.

One Black girl alleged in a court action that Fosdick, “with force and violence…did drag her out of her seat and violently shoved, pushed, beat, and struck her, driving her away from the school.” Ultimately, the State Supreme Court in 1868 found in favor of defendant Fosdick “with costs adjusted at $192.48.”

Buffalo Blacks never succeeded in obtaining integration. A separate white-run school for Blacks, they called an “African school,” was established in a ward where only 10 percent of Buffalo’s Blacks resided. Frederick Douglass described such a school as “a low, damp, dark cellar better fit for an ice house.” Buffalo’s superintendent, however, described the building as “the good effect of the enlightened and liberal policy of the Common Council.” In 1880, the Buffalo Common Council closed western New York’s last “African school.”