Minister Farrakhan On His Music

Minister Farrakhan On His Music

Interview conducted by Dennis Speed on May 9, 1995, with

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan

and published in The New Federalist, June 12, 1995.

Dennis Speed, interviewer: I think that certainly for those who know your attachment to music, your practice and mastery of the violin, which has been part of your life for most of your life—almost your entire life—has shown a side to the world of Minister Louis Farrakhan that they never expected to see. It’s also posed an interesting question, which is: Why is it that you have this love of Classical music, and why is it that you don’t see any paradox between your love of this Classical music and its supposed European roots? Why is that a man of your stature and also of your persuasion, your entire orientation, sees this as complementary to what you do?

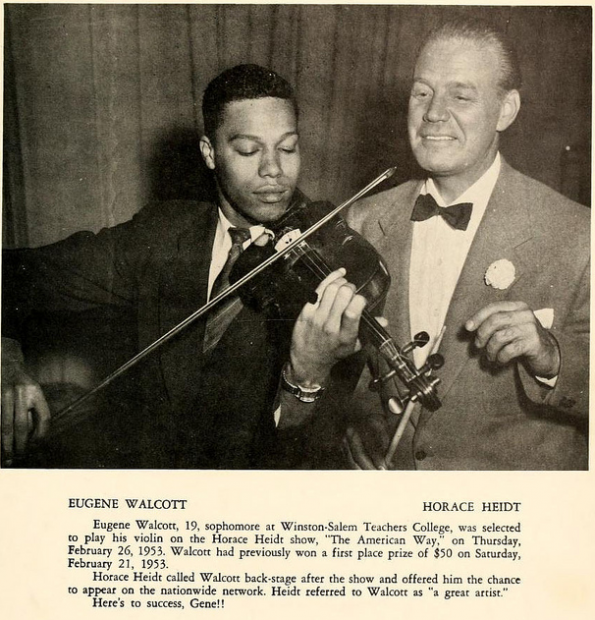

Minister Louis Farrakhan: Well, I know it’s complementary to what I do. The paradox is explained in growth. First of all, my mom gave me the violin and secured my teachers for me; and from an early age the only jazz violinist that I ever knew of was a man called Stuff Smith, whom Jascha Heifetz loved to listen to, because he was an absolute genius in playing jazz violin. I never was interested in playing jazz on the violin, although jazz was germane to the Black experience.

But the Classical music touched me. When I went to music school and we studied solfeggio, we studied the technical side of music, counterpoint, and then we had chamber music, we had orchestra, we had trio, and then we had our individual violin lessons, and I would stay in the music school all day, and during my free time I would go in a music room, and a dear friend of our family, who I think is still living, would give me hot chocolate, and I would sit in front of a huge, well, it was like a stereo system, but it wasn’t a stereo system at that time, and listen to Heifetz, and Joseph Segetti and Mischa Ellman and so many of the great violinists of that time—Efram Zimbalist. And I would sit for hours; and tears would fall out of my eyes at the beauty of this music.

Music comes out of the experience of people. There would be no jazz, no blues, no gospel, if it were not for our experience. So slavery and the suffering of the people gave rise to an expression out of that era. And if it’s not paradoxical for white folk to sing blues and play jazz and sing gospel, and we say “Whoa, look at this!”—they are tapping into our soul; and, through tapping into our soul, they’re tapping into the life experience that gave birth to that soul, that gave birth to this musical expression.

Now, European society, if you look at that society, in the Renaissance period and the period that gave birth to much of the great Classical genius of that period, when I listen to that music, I don’t hear “white.” I don’t hear “Jewish,” I don’t hear “black.” I hear God, speaking to human beings through a universal language from a unique experience historically and culturally at that time.

So I can tap into Beethoven, and I can live him, and to me, I find more harmony with that period than I find with slavery. Because my spirit has always been free. I don’t see myself as an enslaved person. I don’t like to sing blues. I like to hear them. But I don’t talk about how “I lost my baby.” I haven’t. “I ain’t got nobody.” I’ve got everybody. “I don’t have no money.” I’ve got money. I’ve got friends. So if that’s you, you sing the blues. I’ll enjoy it, but you sing it.

But for me, the free spirit that I feel in the expression of Handel, in the expression of Mozart, in the magnificence of Bach—I identify with that. “But these are white people.” I don’t know anything about their color. I never saw them. I wasn’t introduced to their color. I was introduced to the God in them, manifested in their music. And that’s the way the world is introduced to the God in us, through the manifestation of the art-form that comes from our cultural experience.

So to me, that’s why music is so important to bridge the gap between human beings in time periods; because here’s how you can tell whether something is of God. It is ageless. It lives. And the Classics live. Elijah Muhammad loved the Classics, and he was the exponent of blackness. But blackness is not national, he said. Black is universal, since everything started in darkness and comes out into the light. So when you are universal, then you are embracing that which is universal. Truth is universal. God is universal. Life is universal. Music is universal.

So the paradox, if I may say that, is this: When I accepted Classical music and fell in love with this music, that music connected me to the human family. I loved black people. I hurt over the pain of black people and wanted to fight for black people, but not to the exclusion of the rest of the human family.

So the paradox, if I may say that, is this: When I accepted Classical music and fell in love with this music, that music connected me to the human family. I loved black people. I hurt over the pain of black people and wanted to fight for black people, but not to the exclusion of the rest of the human family.

When I met Malcolm X and the Hon. Elijah Muhammad, they narrowed my focus. Elijah Muhammad took me right out of music. He said, “come on out of there. I want you to be a preacher.” So when I put that violin down and narrowed my focus to black people, it was not harmonious with my music. So I began writing a new kind of music, based on the calypsos, and the calypsos began to reflect the racial thing, so I wrote “A white man’s heaven is a black man’s hell.” Have you ever heard that?

Speed: Yes, I’ve heard that.

Min. Farrakhan: Then I wrote plays and whatnot around the experience of black people. Well, I’m not caring about Europe, or I’m not caring about Asia, or I’m not caring about Mexico, Central and South America, I’m caring about the suffering of black people in America, Africa, the islands of the Pacific, the Caribbean, wherever black folk are.

And then in 1973, I brought my violin to Chicago and I played for him, in late 1973. And he liked it. He said, “You really can play that thing!” Then in ’74 I played for him again, after the Savior’s Day convention, right in this house. My brother, God rest him, and a trio, played ballads, very few Classical pieces, we played show tunes, pop things. He really loved it. And then after that, he called me one day and said, “Could you come out and bring your violin with you?” He said, “There won’t be anybody here but me and you and Sister.”

So I came out and brought my violin. At the end of dinner, we came over here, by the piano, and I played. And after I played, he said, “Didn’t you play that for me the last time you were here?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He said, “Well, don’t you know anything new?” “No, sir, I don’t.”

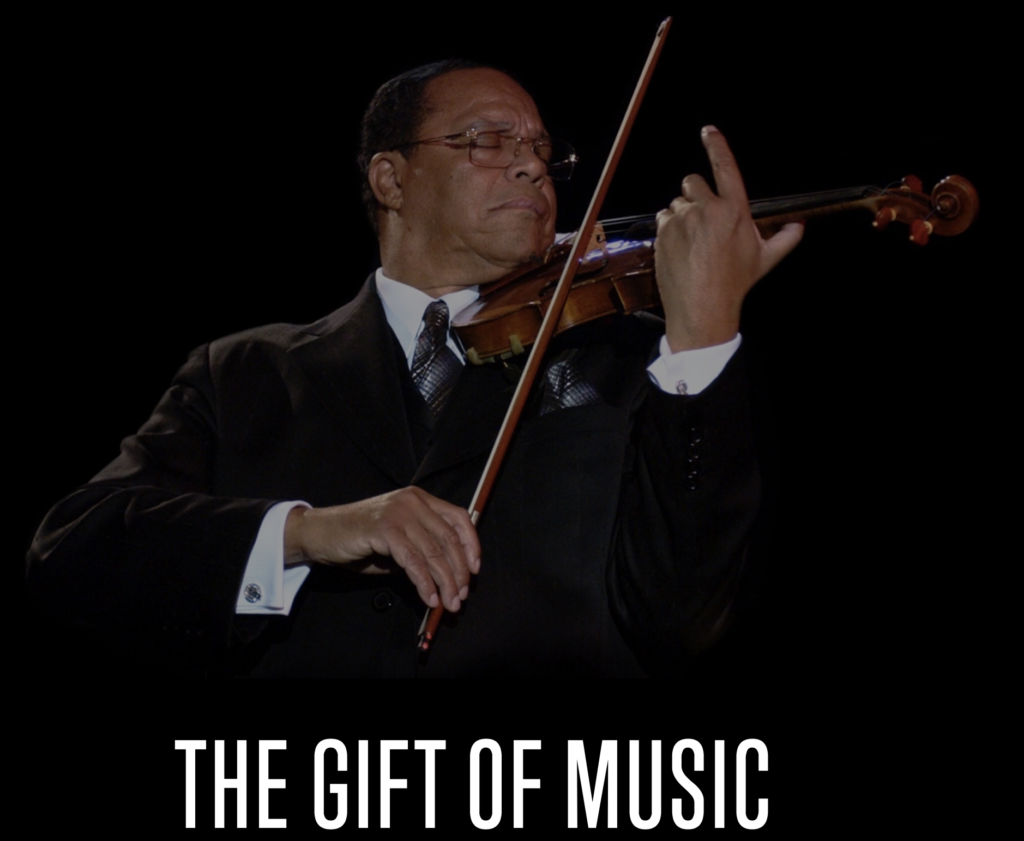

And he frowned. That was ’74; and in ’93 I performed what I had never played in public ever before, the complete Mendelssohn violin concerto. And for two years, I had to work. Now you get me back into my Classical roots! Uh-oh. What does that mean for Farrakhan? His breast expands, his horizons expand, and he sees the pain of black people; but now, through music, he sees the pain of the total human family. This is preparation for a universal message, that he ultimately has to give to more of his people. So I see that Elijah Muhammad knew this, and he was telling me, “go back and get your music and play something new.”

So that’s my connection to Classical music, and I pray that God will allow me to live a little longer, because I’m working now on the Beethoven violin concerto, the Bruck violin concerto. I want to ultimately play the Tchaikovsky and the Brahms; and if I can do those five concertos, and do them well before I leave this planet, and get a violin that is a world-class violin, I’ll be, sho’nuff, a happy soul when I leave this earth, because I will have seen, by God’s grace, the empowerment of our people, a reconciliation, hopefully, of us, the wounds in our families being healed, the rise of a righteous group coming out of America, to affect the world. And I [will have] done what God wanted me to do; and I can leave happily, and look at this magnificent life that I’ve created. And I can thank Him and thank Him and thank Him, for just being alive, coming into this world, in this magnificent creation of His, and now it’s time to go.

But I will have produced children and young people who will take things on to new levels. And I believe God will give me a vision of those new levels, so that my end, death, will be so precious and perfect and meaningful; and I say this to you, in conclusion: What is life all about, but to live it in service to the Creator of life and to further the evolutionary development of His Creation toward perfection? What is better?

That’s why I believe death must come to us all, because we’re not perfect; and only through the attraction of male and female, and the production of new life that we can feed and develop to minimize our mistakes and make newer ones, but certainly not repeat ours, that they are more close to the perfection that God desires than we are, so we go off the scene and give rise to a better generation. And they go off the scene, giving rise to a better generation. And God continues in every generation.

I’ve learned just to look at my life, and look at life, and to just be thankful for being a little speck of dust that God allowed and formed into a human being. And I’ve got to serve Him in this in return, to the best [of my ability]. And I can never die; because the I in me, is Him, who is eternal. And I don’t think I would have known that lesson if Mr. Muhammad hadn’t given me the nod: “Don’t you know something new?” and then frowned.

Now I can tell him: “I’m learning a few new things.”

So may God bless you and thank you for the interview. I feel very good about it, because sometimes I don’t even know what I know, until I’m asked; and the most beautiful thing of all is to probe somebody, to extract from them what is revealing, so that they don’t return to the dust keeping things that should have been and could have been shared with others.

Learn more about The Minister’s Music here: https://www.letschangetheworldmusic.com/lcw