King Cotton: The Engine for the Industrial Revolution

Dr. Ridgely Abdul Mu’min Muhammad

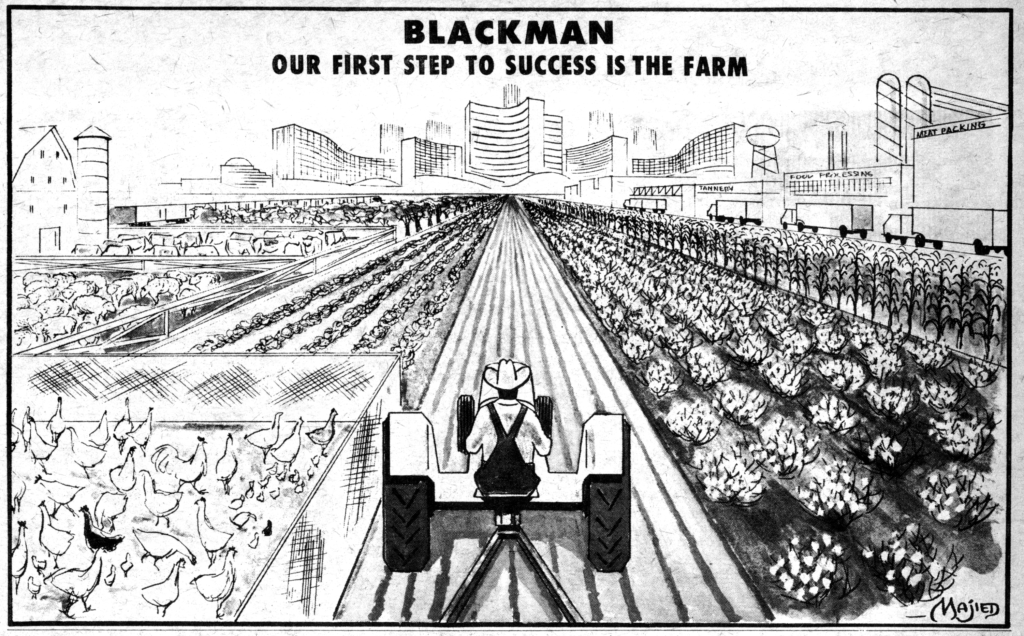

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan told me to tell you that the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad said, “The farm is the engine of our national life.” The engine of our nation is what pushes the nation forward. Without the farm we are lost. Without agriculture we have nothing. Because of the bad treatment under slavery and under the sharecropping system, our elders left the land seeking a better life in the cities. They left with a bad taste in their mouths, so that when schemes were fashioned to take the land from them, they did not put up a real fight. They took the little money and let the land go.

The companies in the middle between the farmer and the consumer—including the trucking firms, cotton mills, storage facilities, textile mills, weavers, clothing manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers—pocket that money. This is why the farm is the engine for the rest of the economy. Not only does the farmer feed the people, he supplies the raw ingredients needed to make the everyday products that allow others to get rich.

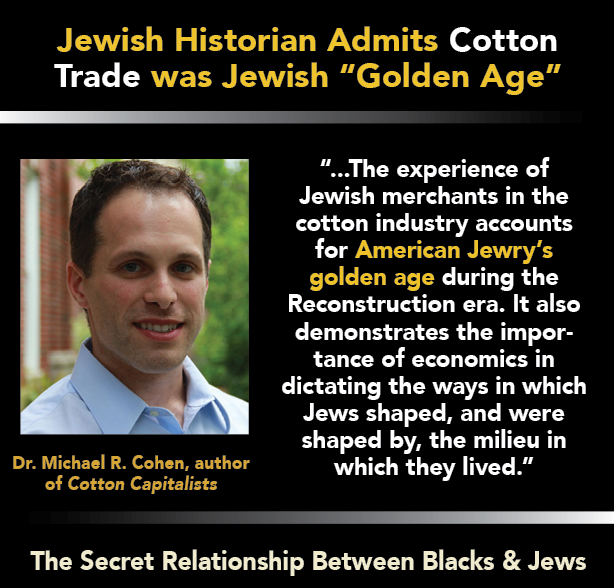

The history of “King Cotton” is a prime example of how the farm is the engine for the economy of a nation, and The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Volume 2 (TSRv2) also introduces us to how cotton became the engine for the Industrial Revolution not only in America but in Western Europe as well. According to TSRv2, during the 1800s a sizable percentage of the South’s massive cotton shipments were destined for the northern American industrial centers, most often ending up in the factories of Jewish clothing and textile manufacturers. Seventy percent of the cotton harvested in America was used to make dresses, coats, hats, slacks, and shirts, along with household goods like curtains, sheets, pillow cases, and towels, all of which constitute what used to be called the “needle trades.”

TSRv2 quotes the Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, which states: “The needle trades have been the most distinctively Jewish group of industries in the United States.” By 1880, practically every large city had some important clothing manufacturer. According to scholar Rabbi Allan Tarshish: “In New York City, 80 percent of all retail, and 90 percent of all wholesale clothing firms, were owned by Jews.”

In 1860 alone, the needle trades devoured 423 million pounds of slave-grown cotton, generating revenues of $116 million. That volume increased by 1910, generating $617 million. In the “needle trades,” Jewish historian Isaac Markens points out, 234 of the 241 clothing manufacturers in New York City were Jewish firms, while the majority of the 30,000 people engaged in the clothing trade throughout the United States were Jewish.

According to TSRv2, by 1860, cotton manufacturing had become the leading industry in the U.S. A single bale of cotton, picked by a Black man or woman for the meager daily wage of 43 cents, in the hands of Jewish clothing manufacturers in the Lower East Side of New York, could be transformed into 215 pairs of jeans, or 690 terry bath towels, or 1,256 pillow cases, or 2,104 men’s boxer shorts, or 3,085 diapers, or 249 bed sheets—and not a penny of these value-added cotton products accrued to anyone with black skin. By 1880, 6,000 clothing firms nationwide were able to manufacture clothing worth $209,000,000. The milling of cotton, which turned fiber into fabric, also became the domain of Southern Jews. Mill owner Jacob Elsas was the largest employer in Atlanta and retired in the early 1900s “with a cool $10,000,000 to his credit”—that’s $233 million in today’s money.

To highlight the tremendous impact of cotton on other parts of the American economy, let us bring the cotton industry up to modern-day economic conditions. With raw cotton selling for $0.60 per pound, a 480-pound bale of cotton pays the farmer $288. From a single 480-pound bale of cotton, one can manufacture 1217 T-shirts, or 215 jeans, or, most surprisingly, 313,600 $100 bills. Most people think that paper money is made of paper, whereas in fact the American paper currency is made out of cotton. So now at today’s prices for T-shirts and jeans, one $288 bale of cotton produces $3,042 worth of T-shirts ($2.50 ea.) or $5,805 worth of jeans ($27 ea.). If the currency manufacturer printed $100 on each paper bill, one bale of cotton would produce $31,360,000 worth of paper currency. So King Cotton is definitely the engine for producing wealth in America.

However, not only does cotton produce wealth, but it also produces jobs for those outside the farming belt. The textile industry transforms raw cotton to cloth, employing workers for bale opening, blowing, carding, spinning and weaving. We estimate that it takes 7 workers to transform cotton to cloth from one single bale of cotton. Therefore, the farmer growing cotton is the engine for economic development in the rest of the economy.

But the importance of cotton is far greater than one might think, in terms of the development of the whole Western economy. According to Gene Dattel in Cotton and Race in the Making of America, the Industrial Revolution itself largely began with the textile industry in Britain. Advances in spinning and weaving moved the industry from the cottage to the fully integrated factory or cotton mill. Here was the first major modern industry to move across the globe in search of lower production costs and larger markets. The wealth generated by the cotton industry itself spawned the legendary critics of the industrial revolution—Karl Marx and his colleague the cotton magnate Friedrich Engles, who outlined an alternative economic system.

According to TSRv2, the wealth generated by the cotton industry in England became the base for the establishment of one of the greatest banking families in the world, the Rothschilds. The Rothschilds started in the textile industry as merchants who distributed finished textiles and raw cotton bales imported largely from America. In 1798, a disagreement between the Rothschilds and their Manchester-based cotton wholesaler cut patriarch Mayer Amschel Rothschild off from his supply. This is when Rothschild’s third son, Nathan (1777-1836), decided to relocate to Manchester, known as the “international emporium for cotton goods,” to establish a direct connection to the source. From here Nathan teamed with other merchants to take economic advantage of the era’s chaotic political events to monopolize markets and inflate profits.

Innovations in cotton cloth manufacturing transformed the European textile market from producing wool clothing to producing cotton apparel. Between 1783 and 1883, wool dropped from 77 percent of the European textile market to 20 percent; correspondingly, cotton rose from 6 percent to 73 percent of the market. The slave-holding South in America in 1800 exported 56 million pounds of cotton to England. That figure rose to 1.39 billion pounds of cotton by 1860. By the eve of the American Civil War, almost 4 million people out of England’s population of 22 million were dependent on the cotton industry, where the vast majority of the raw cotton came from the slave-holding South in America.

This brief outline of economic history demonstrates how the European Jews who came to America used cotton as the engine for the development of their wealth. They controlled the cotton industry from the “land to the man.” They controlled its production by lending slave-owning cotton planters the necessary capital to produce the cotton. They controlled the trade in raw cotton and its manufactured products of clothing and household goods. They had so much control in fact that, according to Isaac Markens, a Jewish immigrant who became “one of the largest cotton operators in the world” actually “held the key to the cotton trade of the world.” In the manufacture of certain apparel, the Jews “have secured a monopoly.”

Black people in America can also make cotton the engine for a revitalized Black economy, if we decided to control our consumer behavior by buying only products produced by our own textile mills and clothing manufacturers. Since we do not have such industries, it makes no sense to grow cotton on our farms at today’s market price and basically give it away to the textile and clothing industries, which will wax wealthy off each bale of cotton, while the farmer takes all the production risks for just pennies on his invested dollar. What TSRv2 has revealed to me is that now we must study how The Honorable Elijah Muhammad set up clothing manufacturing and retail outlets, so that we can use our farmland and talents to make ourselves wealthy once again.

(Dr. Ridgely A. Mu’min Muhammad, Agricultural Economist, National Student Minister of Agriculture, Manager of Muhammad Farms.)