Archie Bunker & White Supremacy

Jewish TV Execs Knew Archie Spread Hate

The death of television actor Carroll O’Connor inspired much reminiscing over his role as the “lovable bigot” on the 70s situation comedy All In The Family. O’Connor played Archie Bunker, a lower middle class white man from Queens, whose most prominent contribution to American culture—according to his own admirers—was his weekly spewing of a barrage of epithets directed at ethnic and non-white Americans. To Archie, his fellow citizens could be variously reduced to “spics,” “yids,” “spades,” “niggers,” “wops,” “dagos,” “gooks,” “coons,” “spooks,” “hebes,” “jigs,” “polacks,” “meatheads,” “chinks,” “jungle bunnies,” “black beauties,” among other vile indignities.

His racial philosophy and historical acumen fit nicely into the middle-American consciousness. Archie’s version of the Christianization of African Blacks: “dragged them outta trees and right down to the river.” And he admired “the way you people worked yourselfs up from snakes and the beads and the wooden idols, right up to our God.” Of the threat of Blacks moving into his neighborhood: “What are they gonna do for recreation? There ain’t a crap game or a pool hall in the whole neighborhood-there ain’t a chicken shack or a rib joint within miles.”

American television viewers made All in the Family the most popular show on television, made O’Connor the highest paid actor and made Archie Bunker an American icon. He became the subject of an “Archie for President” campaign and the chair in which he rested his racist backside was enshrined at the Smithsonian Institute. He is like most whites, according to 61% of Americans surveyed—except in one respect: “When colored folks move next door, he didn’t move.”

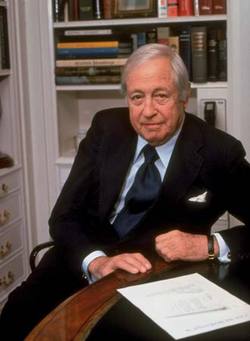

Archie Bunker was the first racial bigot to be taken to the collective heart of mass America, and at an astronomical rate of $120,000 per minute to purchase commercial space on the show, Archie’s brand of “humor” became the mainstay and foundation of the CBS network. But less is known about the roles of the people behind the show and their motives for treating America to more racist dogma than had ever been broadcast up to that time. CBS president at first reacted negatively to airing the show. Paley, a Jew, was sensitive to the racial vulgarities that the show’s writers intended to put in the mouth of their star. But other CBS executives convinced Paley that the new show, produced by two other Jews Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin, would “usher in a new genre of comedy.” They reasoned that the program would actually combat bigotry by poking fun at it and that it would help viewers get an insight to their own prejudices.

When it first aired on January 12, 1971, the nervous CBS brass braced for a negative reaction and hired extra operators to field an expected torrent of calls from irate viewers. They introduced the show to viewers with a documentary-like proviso: “The program you are about to see is All in The Family. It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.” Once the show aired it became a major hit and garnered a Saturday evening viewing audience of 60 million. It held the number one ratings spot for five straight years. Early on, CBS commissioned a study which they hoped would demonstrate that the show “helped diminish bigotry.” When the study came back it actually concluded that—far from diminishing bigotry—the show “actually reinforced prejudice.” Paley’s biographer recounts the internal events at CBS:

CBS broadcast group president Jack Schneider brought the report to Paley, “What shall we do with it?” Schneider asked. “If we release it, we’ll have to cancel the show.” Replied Paley: “Destroy the study. Throw it out.” [Smith, p. 494]

Though greedy CBS executives destroyed that report several other independent investigations confirmed the CBS results. Studies done between 1974 and 1976 in America and Holland analyzing the effect of Archie Bunker’s bigotry found that the show tended to “reinforce prior prejudices.” In other words, upon hearing Archie Bunker, racists became more entrenched and comfortable with their twisted racial notions and even found a more acceptable way to express them. None of these studies seems to have created the slightest bit of concern for the show’s producers who knew of their results but then chose to air the profitable show regardless of its promotion of race hatred.

Paley, Lear and Yorkin continued to maintain that All in the Family was a breakthrough race therapy session for America, even while Blacks and any other non-whites in Archie’s narrow vision suffered the weekly “comic” diatribe of hate speech and American intolerance. Interestingly, one epithet which was absent from Bunker’s caustic vocabulary by conscious policy was the term “kike,” which Lear explained “was from another decade” and connoted “real hate.” Black psychologist Alvin Poussaint sounded the alarm about the show from the start in Ebony magazine (June, 1972):

It’s a very dangerous show because it’s disarming. Blacks, for their own survival, should be in a posture of being very angry with bigots, of seeing bigots as enemies-as people who are dangerous to us. We have to see the Archie Bunkers as our adversaries feel that the show is so dangerous it should have been taken off the air long ago.

But Archie Bunker survived. Archie’s creators Lear and Yorkin continued to collaborate and produced white-written “Black” shows like the Jeffersons, Sanford and Son, Good Times and What’s Happening, which were little more than warmed over minstrel shows laced with ethnic slurs, intra-racial insults and chock full of old time negro buffoonery. The Jeffersons, for instance, reportedly never had a single Black writer.

O’Connor’s death represented more than the loss of an actor. Teary-eyed tributes to O’Connor upon his recent passing looked beyond Bunker’s undiluted vitriol and some went so far as to confer upon him the mantle of race visionary. Every TV network eulogized the man as if he were a Nobel prize winning diplomat and replayed film clips of his “lovable” diatribes. Despite all of the roles played by O’Connor in his acting career, last week America was mourning the only one they will actually miss—Archie Bunker. The collective sorrow America displayed for the loss of their beloved “national bigot” provided a window into America’s heart.

Blacks ought to recognize that when white America hears Archie Bunker, they instinctively harmonize, “Those Were the Days.”

Sources:

Sally Bedell, Up The Tube (New York: Viking Press, 1981)

J. Fred MacDonald, Blacks and White TV (Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1983)

Charles Sanders, “Is Archie Bunker the Real White American,” Ebony, June, 1972.

Sally Bedell Smith, In All His Glory (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)