Anti-Semitism and the Souls of Black Folks

By Jehron Muhammad

During an interview from his home in North Philadelphia, sociologist and W.E.B. Du Bois historian Dr. Anthony Monteiro responded critically to a recent attack by the Simon Wiesenthal Center concerning the scholarship of Dr. Du Bois.

Du Bois is the first Black Harvard graduate to receive a PhD, and if compared to influential American musicians, one would immediately think of America’s greatest composer and orchestra leader, Duke Ellington. “The Duke,” as he was affectionately known in the music world, was second to none, and the compositions he left us span three-quarters of a century and chronicle the American Dream, which Langston Hughes called “a dream deferred,” for many of this country’s citizens suffer discrimination to this very day.

For the Simon Wiesenthal Center to make the recent claim that this scholar-turned-activist, whose prescriptions for Black development took center stage in the pages of the NAACP’s Crisis Magazine, had at one time been “under the influence of the genteel anti-Semitism he absorbed at Harvard and German universities,” is not only unscrupulous, but, as Monteiro said, “a bunch of horse crap.”

The Wiesenthal Center attempts to label Du Bois a reformed anti-Semite using his original writing in Souls of Black Folk concerning the exploitation of Blacks in the south by Russian-Jewish immigrants, but that charge of anti-Semitism is debunked by the Nation of Islam’s 512-page book The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Vol. 2 (TSRv2).

The original printing of Souls of Black claimed that the southern region “had been ruined and ravaged into a red waste, out of which, only a Yankee or a Jew could squeeze more blood from debt-cursed tenants.”

The language of Souls of Black Folk captures the era and the circumstances under which Black folks who resided in the South lived. The book, which was considered the most important work “in classic English” produced at that time, caused Langston Hughes to single it out: “My earliest memories of written words were those of W. E. B. Du Bois and the Bible.”

In addition, in the chapter titled “Of the Black Belt,” a U.S. government report gives credence to Jewish merchants’ exploitation of Black “planters.” The TSRv2 chapters titled “Forty Acres & the Jews” and “All About the Benjamins” present Jewish scholarship that supports all of Du Bois’s findings.

Dr. Monteiro’s response says it all: “So what he (Du Bois) observed in a lot of ways as anecdotal turned out to be more substantive.”

Du Bois observed the exploitation of Blacks by “Yankees and Jews.” But in the 50th-anniversary edition of Souls of Black Folk, he removed the reference to Jews because Du Bois—who worked for the NAACP alongside many Jews and in the late 1930s during his travels in Germany discovered Jews being oppressed—didn’t want his work, according to Monteiro, to be construed as anti-Semitism.

“If Du Bois had allowed the above words to stand alone one could claim that as insufficient,” remarked Monteiro. What is clear, “and this is what he was getting at,” said the Temple University African-American Studies professor, “(is) a new form of exploitation. It was more severe than the earlier form (of) slave labor. It was more along capitalist lines.” That new form of exploitation, also called neo-slavery, or peonage, was sharecropping—a slave-labor system that had its origins in the Talmud.

And as Monteiro added more clarity to this all-but-forgotten period in history that short-circuited African-American emancipation and thwarted the possibility of Black economic parity, he also explained that under the new system of exploitation “cotton production increased under Jim Crow as opposed to under slavery.”

A common companion argument made by the Wiesenthal Center is that Jewish merchants in the south were sympathetic toward their Black consumers. This is a bizarre claim because of the mountain of evidence by Jewish scholars stating otherwise. Indeed, to claim fair treatment by all Jewish merchants because of the benevolence of a few is as absurd as applying the anti-Semitism label to all African-Americans; something the Wiesenthal report actually tries to do.

To suggest—as the Wiesenthal Center report does—that Blacks “nationwide show higher levels of anti-Semitism than do whites” based on African-American criticism of Jewish errant behavior, is like calling someone an unfit parent because he reprimands his child when he/she is wrong.

The Wiesenthal report is actually supposed to be a serious critique of the mostly Jewish scholars, rabbis, and academicians like Du Bois whose scholarship is contained in The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Vol. 2. The trouble is the report makes claims—like good treatment by a few individuals represents an entire group—that can never be substantiated.

“I don’t think that claim can be made,” said Monteiro. In fact, as he points out, “oppressing” Blacks was a part of the “whitening” process. “That is the whole point. As other immigrant groups like the Irish, Italians and Poles and other Russians wanted to be accepted; and acceptance meant to be White,” said Monteiro, whose forthcoming book on Du Bois will capture his “Thoughts for a Philosophy of Human Science.”

Being specific, he highlighted Irish oppression. “The Irish suffered savage oppression at the hands of the English, but that did not stop them from being savagely oppressive and violent toward African-Americans.” According to TSRv2, the task of hunting down and persecuting runaway or rebellious enslaved Blacks fell to the newest European immigrants, primarily the Irish.

He also mentioned the fact that there is much written about the “whitening” process. This includes “recent scholarship by Karen Brodkin entitled, How Jews Became White Folks,” said Monteiro. In addition he cited the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who discussed the fact that “Jews had been historically oppressed in Europe but they were still White people.” And then there is Dr. Frantz Fanon, “who studied the difference between the oppression of Jews and the oppression of Black people,” said Monteiro.

In 1946 Sartre—who Fanon admired—published the acclaimed Portrait of the Anti-Semite, in which he discusses the nature of prejudice. His claim—and this appears to be the position that Monteiro was trying to make through Sartre and Fanon—was that anti-Semitism is not an opinion it “is a global attitude” that dictates one’s world view. So in the context of Sartre’s description, anti-Semitism is only a pretext for a prejudiced mentality seeking the means to oppress.

Whether one totally agrees is beside the point. The history of Jewish exploitation of African-Americans in post-slavery America and the current apartheid-like circumstances experienced by the Palestinians in the Jewish state of Israel—and the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s willingness to spend much time and resources manipulating history and current events—are worthy of note.

If the basis of anti-Semitism, according to Sartre, is one’s global attitude, how one historically has lived his life and how prejudice dictates one’s worldview, then the Wiesenthal Center’s claim directed at Du Bois and The Secret Relations Between Blacks and Jews, is actually its own.

^^

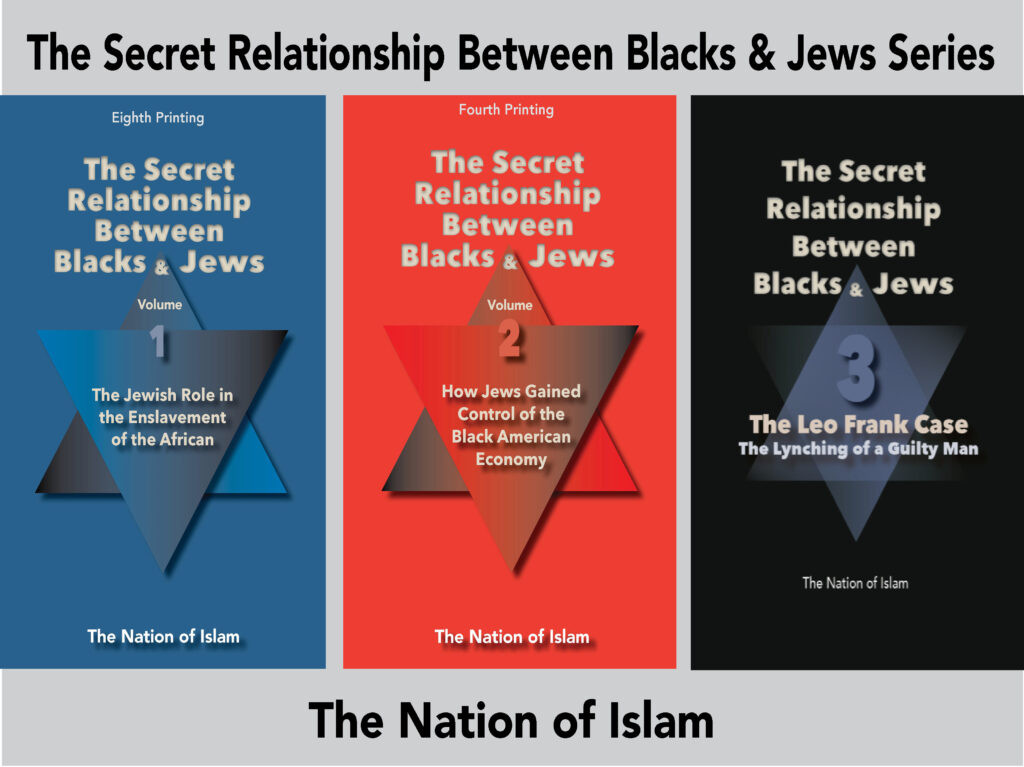

For more on this topic see the Nation of Islam book series The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews. Download the free guide by clicking here.

To purchase the series click here.