A Jewish Scholar’s Critique: The History of Jews & Slavery

Schorsch’s essay is one of the very few Jewish treatments of the subject of Black/Jewish relations that credibly discusses Jewish involvement in the African slave trade. Another being Harold Brackman’s unpublished dissertation which garnered him a Ph.D before he was paid to change his mind. Schorsch’s essay is presented here in pdf form (and below in text form sans footnote markers) with some reservations. For instance, the very first two sentences contain bold yet oft-repeated mischaracterizations of the position of Black scholars on this subject.

Though absolutely justified in refuting the specious yet dangerous accusations that Jews instigated anti-black discourse and/or the Atlantic slave trade, it has become all too easy for Jewish scholars to fall prey to a self-congratulatory delusion of the opposite order. Rebuttal of the anti-Jewish views of extremist black nationalist demagogues does not erase the need to critique problematic biases “at home.”

In fact, Schorsch—like most Jewish “scholars”—provides no evidence that he has ever seen The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Vol. 1, (the very source of the issue he addresses here) and accepts his co-religionist’s characterizations of the work. Yet he nonetheless provides pages and pages of historical data proving the main thesis of The Secret Relationship Between Blacks & Jews—that the extensive interaction between Blacks and Jews—for hundreds of years—was characterized by Jewish involvement in the international trade in Black human beings.

As always, read for yourself and compare with the vast amount of Jewish scholarship that discusses the true history of the Black-Jewish relationship.

ARTICLE:

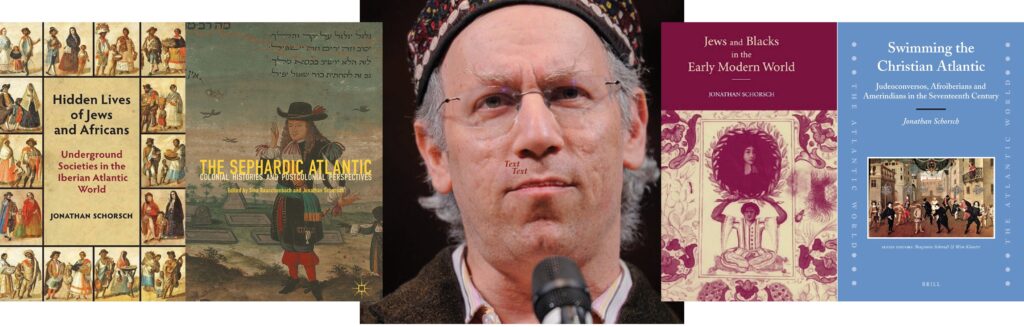

Jonathan Schorsch, “American Jewish Historians, Colonial Jews and Blacks, and the Limits of “Wissenschaft”: A Critical Review,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Winter, 2000), pp. 102-132. Published by: Indiana University Press

Though absolutely justified in refuting the specious yet dangerous accusations that Jews instigated anti-black discourse and/or the Atlantic slave trade, it has become all too easy for Jewish scholars to fall prey to a self-congratulatory delusion of the opposite order. Rebuttal of the anti-Jewish views of extremist black nationalist demagogues does not erase the need to critique problematic biases “at home.”

In this article, I will analyze some of the major works of American Jewish historiography on the early period of European colonialism, tracing the relationship between Jewish agency as historical subjects and black agency as historical subjects as well as race relations and European colonialism. This analysis grew out of an interest in understanding how Jewish scholarly self-cognition has shaped and been shaped by the intermittent but persistent debates about blacks and Jews. Although some works have been written about the number of Jewish academics who “transferred” their problematic ethnicity into the empathetic study of other, less ambiguously downtrodden peoples, the ways in which Jewish scholars have treated “their own” people in the framework of colonial race relations have attracted little notice. The investigation here seemed to me particularly key given the overwhelmingly apologetic nature of Jewish scholarship on black-Jewish relations. I aim here to highlight and question the ways Jewish scholars have approached blacks in a certain phase of Jewish history. Nothing in this article should be taken to suggest that Jews were more anti-black or more responsible for the Atlantic slave trade than any other group, both of which they decidedly were not. I argue for an attitudinal difference, not a quantitative one, in the place given to colonial black-Jewish relations in the narrative of Jewish history.

Next to the growing corpus of American Jewish historical scholarship on the question of ancient rabbinic attitudes toward black people, and a similarly expanding number of studies on late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century black-Jewish interactions, the entire period in between remained for the most part unexplored until quite recently. A book on Jews and blacks in the English colonial orbit first came out in 1998. Of the three book-length histories of black-Jewish relations in the United States written by Jewish historians, only Bertram Wallace Korn’s treats pre-Civil War times. This lack of attention stems from a twofold reluctance: a reluctance to confront Jews as active historical agents acting as a dominant group over subaltern groups, and a reluctance to abandon a Eurocentric perspective on modern Jewish history. These two obstacles would seem to be connected, and they are joined by a third: the often bitter and hostile atmosphere of mutual recriminations has created a situation inimical to scholarship willing to recognize nuances, ironies, and contradictions other than those that would undermine the arguments of the “opposing” side. Paul Gilroy’s plaint about certain small-minded black intellectuals applies as well to some of their Jewish colleagues, who “fear that the integrity of [their] particularity could be compromised by attempts to open a complex dialogue with other consciousnesses of affliction.” Sherry Ortner also rightly points out that the “impulse to sanitize the internal politics of the dominated must be understood as fundamentally romantic.”

A quite visible (though not universally admired) stream of new works in various fields of Jewish studies makes use of some of the new and fruitful approaches inspired by “theory.” Unfortunately, few cover the early colonial period. In some ways, Jewish historiography has been from its outset a form of subaltern studies. Even before “theory,” Jewish historiography-in part because of the rhizomatic and ever-mutating nature of its object of study-had long understood the importance of environmental factors (i.e., other peoples and cultures). Most of these studies, however, took the dialogical history of Jewish identity in the Diaspora resolutely to mean only that dialogue between Jews and Christians, occasionally the dialogue between Jews and Muslims, but almost never with regard to any other group. In his classic work on Jews in the Renaissance, Cecil Roth was at least honest in prefacing his study with the statement that “Of the two cultures with whose interaction this book deals….” This myopic perspective replays most ironically the allegations of Christian oppression of Jews as a bond of intimacy, a family quarrel. Here Jewish history is more Eurocentric than the Europeans (perhaps a common failing of converts and Creoles). This perspective has been most amusingly stated, and with characteristic aplomb, by the “father” of American Jewish history as an academic discipline, Jacob Rader Marcus, in the preface to his three-volume summation, The Colonial American Jew: “The typical American Jew turned his buttocks to the frontier and the wilderness; the culture he knew and cherished was transatlantic, European.” Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi’s demarcation of “Early Modern Jewish History” also neatly exemplifies the Eurocentricity of the Jewish historiography of the period, which goes from “the expulsion of the Jews of Spain in 1492 to the emancipation of the Jews of France in 1790-1.” This liminal period, this threshold to the modern era, marks the crisis in a love story of sorts, but the spurned lover is taken back and all ends happily. Modern Jewish historiography seemingly must replay the courtship and wedding stories Jews told about their coming into the family of Europeans (stories whose bias the non-European cousins might dispute).

My critique will appear ironic to some, given the self-avowed wissenschaftlich (scientific) intentions of some of the very historians I discuss. After all, by the 1930s Salo Wittmayer Baron himself dismantled the historiographical fondness for Jewish passivity in earlier historians, who “readily overlooked the fact that were the Jews mere objects of the general historical evolution, they could not possibly have survived the successive waves of hostility throughout the ages.” More specific to my topic, by 1973 Baron saw that “a reexamination of Negro-Jewish relations in the colonial period would likewise be meritorious.” The critical objectives and aptitude for continued perspectival growth of such master historians are truly admirable, despite their limitations, and it is mostly ingratitude that allows the overwhelmingly Oedipal impulse of scholarship to wield critique in the name of feelings of self-superiority. What is needed, perhaps, is not so much something new, just a reshuffling of the material, a rearrangement jarring enough to make the familiar strange, so that it can be recognized anew. But first, let us take a glance at how some twentieth-century American Jewish historians have covered the early modern period.

The monumental 18-volume social and religious history of the Jews written by Baron stands unparalleled as the culmination of a century or so of modern Jewish historiography. For a history of the Jews, Baron’s work takes great care to frame events and trends in the non-Jewish world. Because of its truly global scope (and luxurious size), Baron’s history devotes admirable attention to Jewish residence in non-European countries and interactions with non-Europeans. Baron’s view on European colonialism is fairly critical, though it has its limits. When in the proximity of Jews, it is noticeably mitigated.

Blacks are, of course, not totally absent in Baron’s Jewish narrative strands. As noted before, he considered the topics of black-Jewish and mestizo-Jewish relations in this era to be worthy of study. He relates, for example, that the first Jewish settlers in the Dutch Caribbean colony of Cayenne “did not prosper” owing to constant French harassment and later “to the uprising staged by the ‘bush Negroes’ (that is, the fugitive slaves imported from Africa, and their descendants).” Baron also recognizes that a relationship existed between Jews and the economy of minorities or subgroups in the colonies. In early colonial Mexico, where “the Indian problem was further complicated by the presence of numerous mestizos, as well as a growing Negro population,” Jews (sic-actually conversos) “were not the sole, nor most important, minority in an otherwise growingly homogeneous society, [and so] they were on the whole treated less severely here than in the developing national states [in Europe]”. Elsewhere Baron offers the intriguing suggestion that the Jewish children and adults forcibly removed by the Portuguese in 1497 to the West African island of Sao Tomè were “chosen to serve as part of an experiment of how the Portuguese could adjust to life in the tropics”.

Rarely, however, are Jews depicted as harshly as other Europeans when it comes to attitudes toward non-Europeans. Portuguese officials in the Far East “retained their Old World prejudices” while the colonial administrators appointed by the Spanish monarchy applied “their racialist approaches even against the background of the multiracial local societies”. But when Jews are the subject of a passage, Baron’s language remains neutral, sometimes even euphemistic. We read, for example, that “clandestine Jews” in early colonial Mexico, sometimes “owned landed property, like their Catholic compatriots, cultivated with aid of Indian or Negro labor”, surely a benign way of putting it. Although Jews are mentioned as planters on Martinique and Jamaica, Baron says nothing about the interactions between these Jewish masters/mistresses and their slaves, nor about the attitudes of slaves of Jews toward their owners. Rather, we have a loud silence. Baron focuses on refuting charges of Jewish participation in the slave trade, but very little otherwise pertaining to blacks attracts his attention. Discussing the high number of African slaves in Cayenne, Baron adds that “There is no evidence, however, that Jews had participated in the importation of these slaves or in the slave trade generally”. The latter half of this sentence certainly stretches the denial rather thin-Jews who could afford, and were allowed, to involve themselves in various aspects of slave-trading did so just like Christians or Muslims-especially considering that he elsewhere mentions such participation. Thus, when forced to talk about Jews as slave traders, such as in the British West Indies, Baron feels the need to insert an apology, though that is not always the case when he discusses non-Jewish slave trading:

Probably there were also some Jewish slave traders in the British and other colonies. Naturally, such employment and trade are highly repugnant to present-day feelings. But this emotional reaction, which has colored much of the historical literature on the institution of slavery, should not blind us to the exigencies and realities of the situation then prevailing.

Baron’s liberalism notwithstanding, he has here erased opposition to or questioning of slavery before “our” times. His dismissal of the “emotional” reaction to slavery leaves little wonder about whose “exigencies and realities” Baron does not have in mind. In any case, the issue is not whether we can stomach the “exigencies and realities” of slaveholding societies but whether we are interested in and brave enough to study them.

Baron consistently attributes progressive views on racism and oppression to Jews and New Christians (the descendants of willingly and unwillingly converted Jews). About the famous Bartolome de las Casas, who at times argued for more humane treatment of the Indians, Baron writes,

[His] eloquent pleas for social justice may well have been stimulated by his consciousness of his Jewish heritage. Americo Castro has convincingly and repeatedly argued that Las Casas was of Jewish descent-a fact which in Castro’s opinion explains not only Las Casas’ mentality and behavioral characteristics…but also his abiding interest in science and history.

Castro’s essentialist argument-and an extravagant one at that-receives no qualification or commentary from Baron. He obviously concurs, because he says elsewhere of a later accused Judaizer, the Argentinian jurist, historian, and writer Antonio RodrÌguez de León Pinelo: “Perhaps it may not be too venturesome to suggest that, like…Bartolomè de las Casas, he became so deeply interested in Indian affairs because of his New Christian antecedents and an understandable affinity to any other group oppressed on racial grounds”. Unfortunately glossed over in such readings of Las Casas’s egalitarianism is the fact that, for a while, he “called for the importation of Africans to spare his native charges.” It was at the impetus of Las Casas that the Spanish Crown provided the first royal license for the monopolistic and mass importation of African slaves to the New World (4,000 of them) to the Dutch Lorenzo de Gorredod in 1518. And, according to Luz MarÌa MartÌnez Montiel, the New Laws promulgated by the Spanish Crown in 1542 at the instance of Las Casas “protected the substitution of Indian slavery by Black slavery.”

Treating Hernando Alonso, a New Christian conquistador who accompanied and assisted Cortes in the 1521 conquest of Mexico, Baron writes: “Possibly disgusted by the enormous atrocities his fellow conquistadores committed against the native population (the memory of those crimes even now prevents the erection of a statue of Cortes in Mexico City), Alonso left the army and soon became a leading cattle breeder and meat supplier to Mexico City”. I suspect that Alonso’s possible disgust may also be Baron’s invention. After all, Baron has just informed us that among Alonso’s rewards for having helped subdue the Mexican natives was “a large estate and Indian slaves.” It was thence that Alonso “retired” from military life. Also, how is one to read Baron’s parenthetical remark? Does it betray criticism for the lingering memory of not wishing to forget the “enormous atrocities”?

Baron significantly fails to even discuss Surinam, the most prominent colonial meeting-ground of Jews and African slaves, though he mentions its earliest settlements by Jews. What he does say about Jews and slaves in the Dutch seaborne empire is relegated to a footnote and captures vividly the limits of a perspective that takes into consideration only one side of a multisided phenomenon:

If Jews did pioneer in cane cultivation in Essequibo, it is further testimony to their enterprising spirit, since they must have paid dearly for the necessary manpower. According to an Amsterdam notarial document of August 26, 1658,…one Abraham Rodrigues had to pay the Company, which enforced its monopoly in the slave trade, 450 Flemish pounds for one male and one female slave, whereas, according to another notarial record, dated November 10, 1659, the Company directors promised to deliver to the colony of Guiana up to 1,000 slaves at the price of but 150 guilders each.

Here one sees in operation the costs shouldered (willingly?) by those who wanted to play the part of the pioneer. What one doesn’t see, the price paid by those who were bought to serve as “the necessary manpower,” lays hidden by their masters’ “enterprising spirit.”

In the three-volume summation of his life’s research, The Colonial American Jew (1970), Jacob Rader Marcus seems interested in blacks only peripherally. Where in Marcus’s summation of Brazilian Jewish history under the Dutch are the African slaves? They are covered by the following sentences:

Associated with Brazil’s sugar plantation economy [with which some Jews and New Christians were involved] was the African slave trade, and this enterprise attracted Jews too. Excluded from the importation of slaves-a company monopoly together with the sale of redwood, arms, and ammunition-they operated primarily as brokers, buying from the company on credit large consignments of slaves and selling them on the installment plan to the planters. Since planters frequently payed their debts in sugar, Jews became sugar brokers also and were heavily involved in the commodity’s disposal. The profits Jews made as slave vendors lay in the high rate of interest they charged on unpaid balances.

Only on page 115 does Marcus relate that “Sugar planting was based on slavery,” and then only to say that “most Jews simply possessed insufficient capital to involve themselves in the industry”-the same reason, no doubt, that prevented so many Christians from entering the same industry. Members of the even shorter-lived Jewish community on Martinique also owned slaves, as summarized dryly by Marcus: “Every householder had at least one slave; seven had ten slaves or more. Of these seven, one had twenty-one slaves, while another had thirty slaves. In all likelihood these two large slaveowners were planters”.

Is the colorless tone a result solely of the mercenary nature of the historical documents as they relate to slaves? Does the technical, economic vocabulary mask an unwillingness to devote the same attention to these Others of seemingly lesser importance? Blacks or slaves are discussed by Marcus only in the sections devoted to “economic life,” except for the case of Surinam, where a few demographic facts including slaves come in the course of the “main” narrative. How lifeless these sentences seem in contrast to the riveting tales of European attitudes toward Jews, of martyrdom at the hands of the Inquisition. Christian members of the West India Company who were insensitive to Jews Marcus calls “emotionally incapable of emerging from the mire of medieval prejudice”, yet he never says of Jews who held slaves or despised blacks that they were emotionally incapable of emerging from the mire of medieval prejudice. Although Marcus himself confesses in the preface that he occasionally stepped out of his “then-perspective” and “permitted myself a value judgment from the vantage point of the twentieth century”, it is intriguing that Jews in history benefit but not other groups in whose oppression some Jews played a role. Put another way: had Marcus written a history of the Jews from the “then-perspective” of various European and American Christians, his book might not evince such a triumphal narrative.

The silence of even so sensitive and progressive a historian as Marcus can sometimes be astounding. Discussing the Jews of Saint-Domingue, where he has just informed the reader of one wealthy Jewish clan that owned a plantation employing 280 slaves, Marcus cites the discovery that “anti-Jewish prejudice was not absent on Saint-Domingue even among the Negroes” (my emphasis). Treating Surinam, Marcus recounts with contempt anti-Jewish discrimination; “Nasty epithets were flung at them, even by slaves” (my emphasis). These uses of “even” occlude so much. It is understandable, he seems to be saying, that white Christian Europeans would hate Jews, but Negroes! What reason could they possibly have for hating Jews? Thus without a trace of irony Marcus responds to the late-seventeenth-century imposition of disabilities onto the Jews by various British West Indian assemblies when he comments, “A representative democracy is not necessarily an unmixed blessing; it can and occasionally does legislate against helpless minorities”. One never would have guessed that black slaves suffered at all in these “representative democracies.”

To be fair to Marcus, he points out on occasion the situational nature of Jewish whiteness-that is, the degree to which Jews and black slaves often existed in a kind of zero-sum power game vis-a-vis Christian Europeans. In his treatment of early Jamaican Jewry, Marcus notes that because of the “presence of so many Negro slaves” Jews were permitted to serve in the military. To which he comments: “In view of this need, the longer the Christian authorities looked at their Jewish neighbors, the less ‘tawny’ they found them”. In contrast, when eighteenth-century Surinam found “the Indians and Bush Negroes becoming less of a problem, the need for Jews in the land seemed to many Gentiles far less imperative than it had been”.

In his coverage of Surinam, Marcus devotes several pages to the issue of black-white relations, mentioning all the major elements. Here is the heart of his treatment:

The chief problem the whites faced vis-a-vis the Negroes…was the threat of servile revolts. By the 1780’s Surinam was a country whose 3,356 whites floated in a vast sea of nearly 50,000 Negroes. The whites felt they were being persecuted by their own slaves! The result was a vicious circle of white insecurity, inducing Negrophobic repression and inhuman cruelty, to which the blacks reacted by murdering their white oppressors and escaping into the jungle. It was common for fugitive slaves to join the Bush Negroes who had been taking refuge in the wilderness ever since the days of the English occupation during the 1650’s. From their jungle villages and fortresses the embittered blacks sallied forth to wage a relentless war against their former masters. Plantation life thus had its full complement of perils, and the Jewish planters led by their own militia captains not only defended themselves against Negro raids but also made frequent retaliatory incursions into the jungle…. That the whole spectacle of Negro-white relations was anything but edifying cannot be doubted, and the sickness of it all is perhaps nowhere more graphically reflected than in one report about a Jewish woman whose apparently groundless jealousy of a quadroon girl led her to murder the unfortunate creature by running a red-hot poker through her. The only punishment the court saw fit to impose on the murderess was exile to the Joden Savanne. Even the nineteenth century brought no abatement of these horrors, for Negro slaves were still being burned at the stake as late as 1832.

Typically, the psychological explanations are mobilized mostly in the case of the whites: their persecution complex, the perils of plantation existence for them. From this account one would think that Surinamese slavery stood sui generis, an unparalleled exception in cruelty and barbarity, instead of as a not-atypical sugar economy. One might assume, since he only discusses cruel treatment of slaves in Surinam, that this was the only place it occurred. Only such an extreme anti-world could produce the kind of anti-Jew who behaved in such ways:

Some writers of the eighteenth century, in attempting to account for repeated flights by Negro slaves, accused Jewish owners of mistreating their charges, an indictment the [Jewish] authors of the Historical Essay [on the Colony of Surinam (1788)] ascribed to anti-Jewish prejudice and vigorously denied. It is a fact, however, that the wars against the French and the Bush Negroes called into being among the Jewish planter class a specific type of individual: the aggressive, brutal fighter, politically ambitions and resentful of every limitation and infringement on his personal liberty.

One would not realize, however, that according to Marcus these same Jews were religiously scrupulous enough to convert their slaves (or at least circumcise their male slaves) to Judaism unless one notices that Marcus mentions this fact (in passing) when treating the Jews of Curacao, who “[u]nlike their Surinamese coreligionists,…did not initiate their slaves into the covenant of Abraham”.

Another section of Marcus’s treatment of Surinamese Jewry shows again how much seems to be occluded:

The women were apparently given even fewer educational opportunities, for they were constantly in the company of Negro slaves who taught them bad habits and spoke to them in the Negro-English dialect. Though the Portuguese Jews kept a watch full eye on their daughters and did not expose them to the crude morals and teachings of the family slaves, superstition was rife, and many people had faith only in the folk medicine of the Negro quacks.

Even given Marcus’s intention to inhabit the “then-perspective” of his Jewish subjects, one wonders just whose voice is being presented (ventriloquized, rather) here. The Jewish sons and daughters might, for example, have been keeping a watchful eye on things their parents did not condone. Although the historical sources speak of the black doctors as quacks, the white settlers dying from tropical diseases likely saw in the seemingly efficacious black folk healers something else. Apparently even the communal board of the Joden Sayanne congregation saw fit on occasion to turn to black healers, as it did in September 1773, when a record from the board’s minutes shows a payment of 48 florins “to the Black…for the cure which he provided to Sarah Tores.” According to Josè Piedra, the “black majority among pre-nineteenth-century Peruvian physicians is suggested by many statistics.” Allison Blakely mentions Granman Quassie (Kwasimukamba), an eighteenth-century slave in Surinam who made his way up the colonial Dutch social ladder, becoming a “renowned herbalist and healer.” Indeed, the “Public Prosecutor often appealed for his help, especially when he had to deal with cases of wisi [black magic, which included poisoning],” and a healing plant Quassie had discovered was named after him by Linnaeus, who received a sample from a Swedish planter visiting from Surinam.

Considering that Marcus rewrote American Jewish history to include women, his oversights regarding blacks might have been otherwise. It is intriguing that the one incident mentioning blacks in the recent biography of Marcus, a highly uncritical book that seems to be little more than a reworking of Marcus’s reminiscences with the author, glorifies their self-empowerment. As a supply sergeant in Europe during World War I, Marcus found himself one day on a train sitting near two black officers (from a segregated, all-black division). “A white soldier entered the car, passed the black officers, and ignored them. One of the black officers stood up, pulled his Colt.45, and said: ‘You salute me or I’ll kill you!’ The soldier saluted.” Here one senses an admiration born of empathy.

Much of the American Jewish historiography from the 1960s continued the monumentalist, nationalist orientation of its predecessors, and Arnold Wiznitzer’s work could easily be included here. A historian of Jewish Brazilian history whose work to this day practically constitutes the field in the English language, Wiznitzer summed up his findings in his now classic book, Jews in Colonial Brazil (1960). There he takes great concern to memorialize every “Jewish” victim of the various Inquisitions. Wiznitzer is also particularly careful about firsts, noting the first Jew in Brazil; the first rabbinic responsum concerning the Americas; the first Jewish builder of bridges, the first Jewish physician and pharmacist, and the first Jewish attorney in the Western hemisphere; the first Hebrew poem written in the Western hemisphere; and so on.

Wiznitzer acknowledges the diverse population of a place such as Dutch Brazil, which included “Indians, Catholic Portuguese, Jews of Portuguese and other descent, Portuguese New Christians, Negro slaves, and Dutch Calvinists”. He seems to have provided as much pertinent data as he found concerning black slaves. Of the earliest time in Brazil, Wiznitzer (who includes the Portuguese accused of Judaizing in his coverage) straightforwardly admits, “It appears that already in that period the heavy work in their mills, farms, and homes was done by imported African slaves”. He mentions that the Jews “dominated the slave trade” in Dutch Brazil, meaning that “[i]t happened” that Jews were the only ones with the cash on hand to buy the slaves imported by the Dutch West India Company. He explains official Dutch support for the Jews in 1640s Brazil, despite growing anti-Jewish sentiment among Dutch Calvinist merchants and others within the geopolitics of colonialism: “[T]he West India Company not only profited from the Jews’ business ability and their services as tax farmers and purchasers of Negro slaves imported from Africa, but regarded them as completely reliable political allies as well”. Wiznitzer also cites a letter from Dutch administrators in Brazil to the highest authority of the West India Company in Amsterdam (the Council of Nineteen) that reported:

Incidentally, slaves generally preferred Jewish owners to Dutch and Portuguese owners, because the Jews usually gave them two days a week free of work, Saturdays and Sundays. The Portuguese allowed them Sundays only, and the Dutch, especially in the hinterlands, made them work also on Sundays, even though it was against the law.

This is the extent of Wiznitzer’s exploration of black-Jewish interaction. While investigating slave subjectivity almost by default (“incidentally”), Wiznitzer has selected a positive report that might help mitigate a negative conception of Jewish slave ownership. Wiznitzer’s paraphrase fails to convey the fact that Jews did not give their slaves Sundays off freely but because they were required to, as they were in other colonies (though in Surinam the Jews asked for and were granted permission to have their slaves work on Sundays). But either something changed in Jewish attitudes or the report is not to be trusted fully, because Wiznitzer elsewhere reports that only a few years later, in 1646, the elders of the Jewish community (i.e., the Mahamad of congregation Zur Israel) were “requested to appear before the Dutch Supreme Council of Brazil. They promised that they would henceforth close their stores and refrain from making their slaves work on Sundays”, in response to charges made against the Jews before the same Supreme Council. It seems that, in any case, Wiznitzer misunderstood his source’s footnote, which might have explained the discrepancy, for it says that despite restrictions some Jews had their slaves carry out certain tasks on Sundays and that many Jews hired out their slaves to (presumably Protestant or Catholic) planters in the interior to work, in which case they ceased getting Saturdays off.

Wiznitzer also refrains from looking into the attitudes of Jews toward blacks or Indians. He cites Rabbi Isaac Aboab’s Hebrew poem about the 1645 rebellion against the Dutch and the eventual ousting of the Dutch and Jews (“the first Hebrew poem written in the Western hemisphere”) but fails to discuss the line in which Aboab refers to the leader of the rebellion, Jo…o Fernandes Vieira: “From the gutter he [Portugal’s king] raised an evil man, whose mother was of Negro descent, a man who did not know his father’s name”. No doubt Aboab’s fears (quite justified) about the significance of a Portuguese takeover added fuel to his passionate denunciation of this enemy, but was the insult to which he resorted in a moment of crisis completely foreign to his everyday sentiments? At least some investigation of the confrontation of these Dutch Portuguese Brazilian Jews with a significant population of black Africans might have been useful.

Other historiographical works on Caribbean Jewish history written in the triumphal mode avoid the question of race and black-Jewish relations to an even greater extent. A 1982 academic symposium on Curacao in honor of the 250th anniversary of the dedication of the island’s Synagogue Mikve Israel-Emanuel is an excellent case in point. The featured lectures by some of the most distinguished Jewish historians working on the Sephardic Diaspora nearly without exception failed to analyze black-Jewish contacts on Curacao, though one mentioned in passing some of the Jewish slave traders of the island. The presentations by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi and Yosef Kaplan, two Jewish historians of the highest order, concentrated on the triumphal narrative of Jews fleeing to the new world of liberties, but the word “slave” was mentioned just once.

The work of Robert Cohen made great use of the historiography on slavery, race relations, and the like. One of his essays, “Early Caribbean Jewry” (1983), attempts to correct studies of early Caribbean social structure because they ignore Jews in the population. Yet his study also situates Jews in relation to the forces of colonialism:

As whites [Jews] undoubtedly belonged to the small apex in the societal model. They had more in common with the ruling elite than just their color…. In spite of being white, however, Jews did not enjoy full political and social acceptance in the white society. As whites, they could not and did not belong to the lower strata. As Jews, they could not belong to the white apex. They were a group apart.

Cohen hopes his demographic study will “see how environmental factors influenced the normative behavior of Jews in the Caribbean”.

Cohen clearly lays out the extent of Jewish slaveowning on certain West Indian islands based on censuses from Bridgetown, Barbados (1680 and 1715); Port Royal, Jamaica (1680); and Martinique (1680 and 1683):

Jews in Bridgetown and Port Royal had a similar household size and the number of slaves is also comparable. Jews in Martinique, however, had more members per household and many more slaves…. All Jewish households in Martinique contained slaves, even if more than one-half had no more than four. One out of every four households had at least ten slaves, however, and fully 10 per cent had twenty. No household in Jamaica had more than ten slaves, and three-quarters of the Jewish households in Barbados and Jamaica had no more than four. (126)

The difference between Jewish slaveholding in Martinique, on the one hand, and Barbados and Jamaica, on the other, derives from “their different economic structure”:

Jews were closer to the white planter class in Martinique than in Barbados or Jamaica. Conversely, Jewish households in Port Royal, Jamaica, in 1680 were remarkably similar to non-Jewish ones…. The similarity is clearly caused by the urban environment. Rural households in Jamaica show a completely different pattern. In St. John’s parish, for example, almost a third of all households had as many as ten slaves, while among the urban population the percentage of such households was only 1.9 per cent, while no Jewish household had as many.

Interestingly, Cohen’s Table 2, “Jewish Household Size and Composition”, makes one wonder about his definition of similarity, because two of the four categories reveal significant differences between Jewish and non-Jewish households in Port Royal. Thus, while 15.8 percent of Jewish households in Port Royal, Jamaica, in 1680 were reported to have no slaves, nearly half (47.4 percent) of the non-Jewish households were also reported to own no slaves. And while 41.8 percent of non-Jewish households claimed to own between one and four slaves, 73.7 percent of Jewish households claimed to fall into the same category. These significant differences-which reflect higher Jewish ownership of slaves within specific categories-remain buried in the table, whereas the similarity that buttresses Cohen’s point and minimizes Jewish slaveholding makes it into the prose.

Nonetheless, Cohen concludes:

The Jews, automatically part of the white apex of Caribbean society by their color, behaved demographically in a very similar way. The differences that occurred between Jews of different islands and certainly between the Jews and the general population were most often caused by social factors, such as urban versus rural location, or by economic factors, such as the occupational structure.

But the Jews were not “automatically” anything, certainly not “white.” The “unhealthy climate” of the Caribbean, according to Cohen, controlled “Jew and gentile alike. In that sense, environmental factors completely negated all possible impact norms may have had upon Jewish behavior”. Whatever Cohen’s cryptic and dubious sentence means, he continues just as cryptically: “Demographic behavior alone, however, does not form the historic process of development. The fact that Jews responded demographically in a similar way to the environmental pressures as their Christian counterparts does not mean that in other aspects they behaved like them.” Again, just what does Cohen mean here? “Even in the comparatively tolerant West Indian society they were discriminated against, economically as well as socially. They were largely an urban population living off trade, while most of the general population was plantation-oriented”. But was West Indian society really comparatively tolerant? Jamaica? Martinique? Tolerant to whom, one wants to ask. Is it possible that Cohen’s elliptical language reveals a subtext behind the seemingly dry and objective statistics? This is a subtext that wants things both ways: Jews had no choice but to adapt to the “environment,” hence owned and used slaves, but even so, never to the extent of the main body of cruel (non-Jewish) slaveowners. Cohen’s excellent, useful collection of data, despite its flaws but also despite its awareness of the colonial context of its objects of study, reflects Jewish historiography’s habit of masking racial attitudes behind quantification. Because slaves had already been “coming under particularly close scrutiny” in demographic historiography of the Caribbean, Cohen turned his attention to the neglected Jews but unfortunately without genuinely integrating their various histories. Peter Novick may be correct to note, as quoted at the beginning of my article, how “those who wrote of blacks as subjects, were overwhelmingly Jewish,” but this would seem to exclude those Jews who remained scholars of early modern Jewish history. Blacks, that is, could safely stand as subjects in their own right only if such subjectivity did not threaten certain conceptions of Jewish passivity and disempowerment.

The best treatment of the history of Jewish participation in slave owning and trading comes not from a historian of Jewish history but from a historian of slavery, David Brion Davis. One look at the structure of his outstanding work, Slavery and Human Progress (1984), reveals the degree to which post-1960s debates about Jews and blacks have helped shaped the telling of “the history” of blacks and Jews. The structural anomaly in the book emerges when the first section-entitled “How ‘Progress’ led to the Europeans’ Enslavement of Africans”-culminates in an entire chapter on Jews. The chapter’s excellence notwithstanding, it is striking that its efforts seem so devoted to showing, usually on a purely numerical basis, that the Jews were minimally involved in the enslavement of Africans. What Davis does provide by way of discussion of Jewish attitudes toward slaves or enslaved peoples surely deserves expansion (and is limited perhaps only by his inability to read Hebrew sources). But, ultimately, Davis has argued himself into the same corner of Jewish passivity: the thing preventing Jews from enslaving Africans and others was Christian persecution and exclusion, but in any case Jewish tradition trained Jews to be benign and beneficent toward other persecuted people, such as their black slaves. Such a defense assumes that power is a kind of zero-sum game in which only those “on top” possess it, leaving everyone else without. But power’s circulation throughout society must be continuously negotiated by all of the involved parties, not just those on top. That Jews might not have ruled should not be taken to mean that they did not exercise power in their own right.

Discussing Surinam, the one case where a large organized Jewish community owned and worked slaves from Africa, Davis writes:

[I]t would appear that neither religious tradition nor communal solidarity had any effect on the unquestioning acceptance of a slave economy…. [The Dutch Guianas] serve mainly as a limiting case proving that, in the absence of discriminatory conditions, Jewish communities could become totally enmeshed in the plantation system.

As in Cohen’s work, Jewish religious tradition is here obviously “progressive,” since it could/should have questioned the unquestioned acceptance of slavery by Surinamese Jews but did not. This kind of ahistorical and essentialized argument about halakhah regarding slaves carries many problems. This branch of halakhah underwent its own transformations between the oft-quoted writings of Maimonides and eighteenth-century Surinam. And again the Jews imitate their environment (note the passive voice: “could become enmeshed in”).

There is something dissatisfying about this kind of apologetic argument, indeed, something unsettling. It is a defensive comparison, one that removes historical agency from the Jews in question and, together with the continual resorting to quantification, shirks the crucial and (to my mind) far more interesting matter of actual relations between Jews and blacks. That this tactic, intentional or unconscious, recurs so consistently in twentieth-century American Jewish historiography suggests the depths of the topic’s unpalatability. It also hints at the extraordinary degree to which American Jewish historiography remains beholden to emotional identification with (and defense of) the subject group it purportedly studies objectively. We are not always as wissenschaftlich as we think.

In my analysis I have taken these historians to task for a variety of oversights, realizing that, of course, each writer differs from the other. Salo Baron devoted the least attention to blacks as a legitimate or interesting subject in relation to Jews, whereas Jacob Rader Marcus made some effort along these lines, however limited. Baron, resorting to a kind of sophisticated intuition, essentialized Jewish attitudes toward other oppressed peoples based on a monolithic (wishful) reading of the response of Jews to their own oppression, and he seemed oblivious to blacks as historical subjects. Marcus, though attentive to the situational pressures of colonialism, continually ended up explaining away or mitigating Jewish involvement in the mistreatment of blacks while failing to understand how blacks might have developed animosity toward Jews based on the social structuration of the two groups.

Of these elder statesmen, Baron had training only in Europe, whereas Marcus studied in both Berlin and Cincinnati (he grew up in Kentucky). Both wrote their accounts after the mid-1960s, when black activists (again) vocalized some of the historical and sociological tensions between blacks and Jews, and also when American historiography began paying more attention — both quantitatively and methodologically — to black perspectives of/in history. But Marcus comes across as far more fluent with the black presence in history than Baron.

The next generation of historians received almost exclusively American training, in addition to having grown up in the United States. Arnold Wiznitzer’s major work on Brazil appeared in 1960, too early to have been influenced by the dramatic changes in the historiography of race. One senses in the others, however, more access to theoretical developments and, more important, a willingness to implement them, as did especially Robert Cohen. Ironically, Cohen’s theoretical adoptions were not integrated deeply enough to undo the narrative desires that placed black subjectivity as an obstacle to Jewish precariousness. Members of neither generation, though often recipients of profound “traditional” (i.e., religious) learning, located themselves within the Jewish community as religious leaders or thinkers, even though Baron and Marcus both possessed rabbinical ordination. Yet their critical wissenschaftlich spirit often stood at odds with their status as spokespersons for Jews and Judaism (as is perhaps true for quite nearly any Jewish academic).

How, then, can one explain the consistency of their oversights? I believe it has far less to do with biography than with narratology. Hayden White suggests that historiographies are “verbal structure[s] in the form of a narrative prose discourse” in which the historian performs “an essentially poetic act, …prefigur[ing] the historical field and constitut[ing] it as a domain upon which to bring to bear the specific theories [s]he will use to explain `what was really happening.'”

In White’s terminology, based largely on Northrop Frye, the Jewish historiography of the colonial epoch chooses Comedy as its explanatory form of narrative structure:

Hope is held out for the temporary triumph of man over his world by the prospect of occasional reconciliations of the forces at play in the social and natural worlds. Such reconciliations are symbolized in the festive occasions which the Comic writer traditionally uses to terminate his dramatic accounts of change and transformation.

Jewish emancipation usually stands in as the climactic festive occasion in Jewish historiography of the colonial world, an event that heralds, if not ushers in, “reconciliations of men with men, of men with their world and their society; the condition of society is represented as being purer, saner, and healthier as a result of the conflict among seemingly inalterably opposed elements in the world; these elements are revealed to be, in the long run, harmonizable with one another.” Indeed, with the possible exception of Baron and his ostensibly global view, all of the historiographies I have covered script a narrative of tentative Jewish redemption in the Americas (with the Americas sometimes figured as emancipation). Already in 1954, on the occasion of the tercentenary of the arrival of a boatload of Jewish refugees from Brazil, Marcus penned a tribute news release, A Tour Through 300 Years of Freedom, which appeared in various Jewish newspapers. This American Jewish redemption occurred (was purchased?) at a price, however, because Jews paid for American modernity by discarding their “traditional,” “moral,” ways. The conclusion to Cohen’s study of Surinamese Jewry puts this conflict the most starkly, but otherwise little differently from the other historians:

[The Jewish community’s] identity, its very self-perception, was not a piece of psychological luggage brought over on the ship from the Old World. It had been shaped by the forces of the local environment. The Surinamese environment may have lost its role in the international market of colonies, but internally it won. It triumphed over traditional Jewish patterns, just as the jungle took over once more the deserted plantations along the river, covering the synagogue and cemetery of Joden Savanna with tropical growth.

Herein lies the comedy’s tragedy. The jungle of modernity overwhelmed the Old World morals of the Jews (uniform and monolithic “traditional Jewish patterns”-as if they, too, had not been shaped by the forces of local environments).

In accord with this view, Jewish relations with blacks stemmed from a thoroughly modern environment to which Jews had little choice but to adapt. (David Brion Davis first assigned a tragic shape to the conflict between Jewish liberation in “the West” and black subjugation.) Jewish redemption through acculturation does not seem to have restored Jewish agency, however. To dwell on slaves and blacks would apparently mar a narrative whose desire is to focus on the successful Jewish escape from Europe, the successful transmogrification of Jews into not-themselves. Yet, ironically, the behavior of Jews toward blacks, goes the argument, was not Jewish. (In exactly the same way the behavior of Christians toward blacks was not Christian?) But some Jews-acting as polyglot Jews and Iberians (among other things)-chose to play at colonialization; these Jews had at their disposal, in addition to the environments “out there,” past Jewish exegesis, folklore, and “scientific” and halakhic literature that also afforded ample opportunity for being fashioned anew for use on colonized blacks (and it remains to be shown just how and when these people resorted to Jewish as opposed to non-Jewish models of thought/behavior). One example lies in the barely modified, unqualified, but always reiterated statements about subhuman Kushite abilities from Yehuda ha-Levy’s Kuzari that can be found in commentaries and translations of ha-Levy’s work from the fifteenth through eighteenth centuries. In short, Jews acted willfully (as rabbis, as tailors, as slaveowners) as much as their external constraints allowed. One of the unfortunate victims of the Jewish slave-trading polemic has been the normalization of Jews within historiography in a subject area so desperately needful of it.

Jewish and black historiographies, birthed and nurtured by “nationalist” purposes, continue to show themselves susceptible to group needs that range from the dangerous to the merely naive. We should not hesitate to rescript narratives when and where appropriate. This is not to argue for (or imagine the possibility of) a “true” or “free” historiography; as White warns, “we are indentured to a choice among contending interpretive strategies in any effort to reflect on history-in-general.” A study of colonial black-Jewish relations offers a perfect opportunity to question the ways in which group needs have erected certain problematic limits on scholarship and to imagine more fruitful alternatives.

NOTES

Black-Jewish relations are my main emphasis, but, because of my desire to construct a framework in which to make sense of such relations, I occasionally discuss Jewish relations with other non-Europeans as well.

The amount written about black-Jewish relations is staggering. The 1984 bibliography by Lenwood G. Davis, Black-Jewish Relations in the United States, 1752-1984: A Selected Bibliography (Westport, Conn., 1984), is hopelessly out of date.

See, e.g., Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession (New York, 1988), 479. He finds that “those [American historians] who have written the most influential studies of white attitudes and behavior toward blacks were almost all gentiles…; those who wrote of blacks as subjects, were overwhelmingly Jewish.” In an insightful fragment that inspired some of my own thoughts, Ezra Mendelsohn, “Should We Take Notice of Berthe Weill? Reflections on the Domain of Jewish History,” Jewish Social Studies n.s. 1, no. 1 (Fall 1994): 26-32, traces the relationship between anthropologist Franz Boas’s writings on blacks and his writings on Jews.

I define American Jewish scholarship purely institutionally: academics who hold positions in departments of Jewish history or a related field of Jewish studies in the United States.

On the rabbinic period, see Ephraim Isaac, “Genesis, Judaism, and the ‘Sons of Ham,'” Slavery and Abolition 1 (1980): 3-17; Daniel Boyarin, “Racism, the Talmud, and African American-Jewish Coalition,” unpublished paper (Berkeley, 1993); David H. Aaron, “Early Rabbinic Exegesis on Noah’s Son Ham and the So-called Hamitic Myth,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 63 (1995): 721-59; and David M. Goldenberg, “The Curse of Ham: A Case of Rabbinic Racism?” in Jack Salzman and Cornel West, eds., Struggles in the Promised Land: Toward a History of Black-Jewish Relations in the United States (New York, 1997). Treatments of black-Jewish relations since the abolition of slavery are too numerous even to begin mentioning specific titles other than those in n.7.

Eli Faber, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight (New York, 1998). I discuss its limitations briefly below.

Bertram Wallace Korn, Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865 (Elkins Park, Penn., 1961). The other two books by Jewish historians are Hasia R. Diner, In the Almost Promised Land: American Jews and Blacks, 1915-1935 (Westport, Conn., 1977), and Robert G. Weisbord and Arthur Stein, Bittersweet Encounter: The Afro-American and the American Jew (Westport, Conn., 1970). See also Harold D. Brackman, “The Ebb and Flow of Conflict: A History of Black-Jewish Relations through 1900,” Ph.D. diss., Univ. of California, Los Angeles, 1977. Two other works treating the slavery era-both written by Jews who work for major Jewish institutions, and both written for a nonacademic audience-were rushed into press in order to rebut the pseudo-academic work put out by the Historical Research Department of the Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews (Chicago, 1991). They are: Harold Brackman, Ministry of Lies: The Truth Behind the Nation of Islam’s “The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews” (New York, 1994), and Marc Caplan, Jew-Hatred as History: An Analysis of the Nation of Islam’s “The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews” (n.p. [New York], 1993). A handful of essays attend to black-Jewish relations in the pre-Emancipation world: Joshua Rotenberg, “Black-Jewish Relations in Eighteenth Century Newport,” Rhode Island Jewish Historical Notes 11, no. 2 (1992): 117-71; Benjamin Braude, “The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 54, no. 1 (Jan. 1997); and Alex van Stipriaan, “An Unusual Parallel: Jews and Africans in Suriname in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Studia Rosenthaliana 31, nos. 1/2 (1997).

Gyan Prakash, whose understanding I share here, uses the term Eurocentrism to mean not “follow[ing] the lead of Western authors and thinkers” but “the historicism that projected the West as History” (Prakash, “Subaltern Studies as Post-colonial Criticism,” American Historical Review 99, no. 5 [Dec. 1994]: 1475).

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, Mass., 1993), 215.

Sherry Ortner, “Resistance and the Problem of Ethnographic Refusal,” in The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences, Terrence McDonald, ed. (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1995), 179.

The most appropriate starting point would have to be the Tunisian-Jewish writer and thinker Albert Memmi. Very much informed by the anti-colonial movement in which he took part, the American edition of his seminal work, The Colonizer and the Colonized (Boston, 1965 [1957]), bears a dedication “to the American Negro, also colonized.” A more recent intrepid explorer who brings extensive theoretical applications to bear on the study of the formation of modern Jewish identity is Sander Gilman. His essay, “The Visibility of the Jew in the Diaspora: Body Imagery and Its Cultural Context” (the B. G. Rudolph Lecture in Judaic Studies, Syracuse University, 1991), investigates how Western categories of race have shaped Jewish self-perception since the nineteenth century. Disappointing, given his focus on the alleged blackness of Jews in some European eyes, is Gilman’s failure to explore how Jewish whiteness arose in response to the blackness of Jews in Christian eyes.

Cecil Roth, The Jews in the Renaissance (Philadelphia, 1964), xii (my emphasis). Nicely corroborating my point about constructing Jews as historical nonsubjects, Roth maintains that the Jewish element was “inevitably…the active factor in the main before the fifteenth century and the passive one thereafter” (ibid.).

Jacob Rader Marcus, The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, 3 vols. (Detroit, 1970), 1: xxviii.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, “Between Amsterdam and New Amsterdam: The Place of the Curaçao and the Caribbean in Early Modern Jewish History,” American Jewish History 72, no. 2 (Dec. 1982): 172.

Salo Wittmayer Baron, “Newer Emphases in Jewish History,” in History and Jewish Historians: Essays and Addresses, compiled with a foreword by Arthur Hertzberg and Leon A. Feldman (Philadelphia, 1964), 101-2.

Salo Wittmayer Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, 2nd ed., 18 vols. (New York, 1952-83), 15: 504, n. 18.

Jonathan Schorsch, “Jews and Blacks in the Early Colonial World, 1440s-1800,” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2000.

Baron held the first post in Jewish history at an American university, Columbia University, where he taught from 1930 to 1963. Born in Tarnow (Galicia) in 1895, Baron received doctorates in philosophy (1917), political science (1922), and law (1923) at the University of Vienna while also becoming ordained as a rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary there (1920). Both in Europe and in the United States he wrote prodigiously and participated actively in many Jewish cultural institutions (Arthur Hertzberg, “Salo Wittmayer Baron,” Encyclopedia Judaica [Jerusalem, 1971], 4: 254). For a fuller treatment of his life, see Robert Liberles, Salo Wittmayer Baron: Architect of Jewish History (New York, 1995).

In terms of my interests here, Baron discusses, among other topics, the impact of the Mexican Inquisition on Indians and particularly on mestizos, the multiracial makeup of the various colonial situations, the differing European attitudes toward the American natives and their conversion, the “frightful decline” of the Indian population, the harsh treatment of the Chilean Indian slaves, and the Portuguese slave trade in Africa (all vol. 15).

Baron’s sympathies seem more easily expressed toward some peoples than others. Thus his “evenhanded” conclusion about the African slave trade-that “this objectionable trade in human beings was as much the fault of the tribal leadership itself as it was of the predominantly Arab slave hunters and the Western traders”-seems marred by his overemphasis on the “general submissiveness of the [African] population to its rulers” (Baron, Social and Religious History, 15: 352). Perhaps African “cultural evolution” was not so advanced as that of the Indians of Chile, who “[t]hough not comparable to the Aztecs and the Incas in their cultural evolution,…fiercely defended their independence and engaged in intermittent guerilla war” against the Spaniards (ibid., 315). The myth that “Africans, lacking reason, were totally subject to the random claims of natural events and the equally capricious demands of their rulers…implicitly legitimated the real enslavement of these same Africans by reasonable European traders” (Wyatt MacGaffey, “Dialogues of the Deaf: Europeans on the Atlantic Coast of Africa,” in Implicit Understandings: Observing, Reporting, and Reflecting on the Encounters Between Europeans and Other Peoples in the Early Modern Era, Smart B. Schwartz, ed. [Cambridge, Engl., 1994], 266).

Baron, Social and Religious History, 15: 67. Hereafter, the volume and page numbers of quotes from this work are given in the text.

The same idea had already been expressed in contemporary Jewish discourse. Rabbi Abraham Saba, exiled from Spain and then Portugal, glossed Deuteronomy 28:32-“Your sons and daughters will be given to another nation”-by citing the sins of the Jews in Portugal, which caused the king to take “the little sons and daughters and sen[d] them on ships to the Snakes Islands in order to establish a settlement there” (Avraham Gross, Iberian Jewry from Twilight to Dawn: The World of Rabbi Abraham Saba [Leiden, 1995], 18).

See note 29.

Hispanic Jewish scholars frequently parrot the same essentialist line, whether or not it derives from Castro. Itic Croitoru Rotbaum, discussing the “Jewish” origins of Rodrigo de Bastidas, one of the first explorers of present-day Colombian territory, provides the following among his considerations: “The peaceful character of the discoverer-conquistador, the gentle methods he always employed in his military actions, the good treatment accorded to the Indians, his impartiality toward his mercenaries…and his thrifty spirit, point to a man of proven Jewish idiosyncracy, very much in opposition to the cruelty and rapacity demonstrated by the majority of the conquistadors descended from Old Christians” (Rotbaum, De sefarad al neosefardismo [Contribución a la historia de Colombia] [Bogota, 1967], 113). Such views of Jewish traits-even with the internalized anti-Jewish Jewish thriftiness-stand as a countermyth to anti-Jewish notions, but are equally fatuous.

Frederick P. Bowser, The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650 (Stanford, Calif., 1974), 325.

Amando Melón and Ruiz de Gordejuela, Primeros Tiempos de Gobierno y Colonización de las Antillas, vol. 6 of Antonio Ballesteros y Beretta, ed., Historia de America y de los Pueblos Americanos (Barcelona, 1952), 253.

Luz MarÌa MartÌnez Montiel, Negros en Amèrica (Madrid, 1992), 172.

Like Baron, the American-born Marcus was ordained as a rabbi. Trained in history at the University of Berlin (Ph.D., 1925) and originally interested in Central European Jewry, during the 1940s, in response to events in Europe, Marcus began to emphasize American Jewish history, which he founded as an academic discipline (Stanley F. Chyet, “Jacob Rader Marcus,” Encyclopedia Judaica [Jerusalem, 1971], 11: 946). Hereafter, the volume and page numbers of quotes from Marcus, Colonial, are given in the text.

Though there is not space here to enter into the question of what Marcus calls the “sin” of present-mindedness, it is not too difficult to see that even “then” a multitude of opinions and options existed, though clearly not all were equally possible. A sixteenth-century Protestant, Mateo Salado, stated that “no man who sold Blacks and mulatos would be able to go to heaven, but rather would be condemned to hell, and that the Pope who consented to this [business] was a drunkard” (Josè Toribio Medina, Historia del Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición de Lima [Santiago de Chile, 1887, 2 vols.; Santiago de Chile, 1956], 1: 60). In 1555, a renegade Portuguese Dominican friar, Fernando Oliveira, penned a blistering and forthright attack on the whole slave trade, Arte da Guerra do Mar (see the reprint edition, edited by Querino da Fonseca and Alfredo Botelho de Sousa [Lisbon, 1937], 23-25). In a letter of 1604, a Portuguese Jesuit named Jo…o Alvarez wrote that “the troubles which afflict Portugal are on account of the slaves we secure unjustly from our conquests and the lands where we trade” (cited in C. R. Boxer, Race Relations in the Portuguese Colonial Empire: 1415-1825 [Oxford, 1963], 8). Josè Piedra, “Literary Whiteness and the Afro-Hispanic Difference,” in The Bounds of Race: Perspectives on Hegemony and Resistance, Dominick LaCapra, ed. (Ithaca, N.Y., 1991), provides some excellent examples of how early modern Afro-Hispanics challenged and resisted the racial classification schemes of the Spanish empire, as does R. Douglas Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660-1720 (Madison, Wisc., 1994). In the mid-1700s, the Quaker visionary John Woolman was encouraging the Philadelphia Quaker assembly to expel members who owned slaves. Woolman himself refused to wear colored clothes, as they had most probably been dyed by slave labor. He also refused to use sugar, produced as it was by slaves (David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture [Ithaca, N.Y., 1966], 490-91). In Surinam itself, the Jesuit-educated Dutch Reform churchman Jan Kals earned expulsion in 1733 for advocating a church that included, as he did in his own parish, Indians, slaves, and free blacks (Allison Blakely, Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of Racial Imagery in a Modern Society [Bloomington, Ind., 1993], 222). And, of course, any reader of the 1789 autobiography of Olaudah Equiano (or Gustavus Vassa), the Ibo who had been enslaved and eventually freed, would immediately recognize the tremendous rhetorical parallels with Jewish pleas for tolerance, if not equality. In short, the question arises as to just whose “then” one is talking about.

One can only admire Marcus’s critical spirit: “There is, as I see it, no more excuse for filiopietism than there is for Judeophobia. Both are departures from ‘truth.’…I have made every effort to set forth the truth-that is, the reliable data-of colonial Jewry in a scientific spirit. I have had to hew out a path for myself through a jungle of fact, half-fact, and ethnocentric schmoose” (1: xxvi). But again, considering that he wrote the preface in 1967, it is revealing which sacred cows were assailable and which were not.

The single anecdote Marcus cites for this Negro anti-Judaism seems rather flimsy. From Saint-Domingue, it runs as follows: “An old fanatical Negress questioned [a mounted figure of] Christ a long time to ascertain who had crucified him. A foolhardy person hidden behind the pedestal replied: ‘It’s Mendez.’ The Negress took some stones and burst into the house of this Jew, whom she would have stoned if he had not fled to escape her blind fury” (1: 93). Perhaps this anecdote could be better read, à la Franz Fanon, as a depiction of the manner by which newly and questionably Christian Africans were trained in (duped into?) Jew-hating. It should be kept in mind to what degree Jews were the objects of social, religious, and political surveillance that needed to be instilled in populations. In Spanish and Portuguese territories, Yerushalmi reminds us, as long as three centuries after the expulsion of Jews from Iberia, “Broadsides posted in public places still displayed a list of characteristic Jewish ceremonies, and called upon the faithful to denounce those whom they knew to be following the execrable rites of the Law of Moses” (Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, From Spanish Court to Italian Ghetto: Isaac Cardoso: A Study in Seventeenth Century Marranism and Jewish Apologetics [Seattle, Wash., 1981], 2).

Even so, Marcus fails to mention that all of the original charters for the Wilde Cust-as Surinam was originally called by the Dutch-which he rightly emphasizes were initiated by “the Jews of Holland, who had haggled successfully for rights” (1: 146), included provisions for subsidizing numerous slaves. Because he repeatedly cites the essays that not only discuss these slave provisions but also translate the original documents (such as Samuel Oppenheim, “An Early Jewish Colony in Western Guiana, 1658-1666, and Its Relation to the Jews in Surinam, Cayenne and Tobago,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, 16 [1907]), it can be assumed that Marcus chose not to include this material.

Marcus errs, however, in estimating the zealousness of Surinamese Jewish planters in this regard. In my dissertation I treat the fading of the conversion and circumcision of slaves in the Dutch and English colonies.

One reads, for example, that the widespread sexual knowledge of the colony’s young men (aged 12-14) comes “only from communication with the Negroes, and from the little care which relatives take at home to restrain themselves in the presence of the children” (Jacob R. Marcus and Stanley F. Chyet, eds., Historical Essay on the Colony of Surinam, 1788, trans. Simon Cohen [Cincinnati, Ohio, 1974], 154; also cited in Robert Cohen, Jews in Another Environment: Surinam in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century [Leiden, 1991], 42). Yet among Jews, “it is the first care of the mothers not to leave their daughters with the Negresses, and never to go out of the house without having them at their sides” (Marcus and Chyet, Historical Essay, 155). Marcus takes this 1788 report at face value, despite the intense polemical interests it had in arguing for Jewish acceptance into European society, which here and throughout entailed proving Jewish distance from blacks.

“Idem, Ao Negro Asolo [?] f.48. cura [?] que fes a Sarah Tores.” Entry of Sunday, Sept. 26, 1773, American Jewish Archives microfilm reel 67, fol. 196. The reel is labeled Records of Jurators of Surinam; Jurator Isaac Nassy, Minutes, 1754-1762, and is a copy of material from the Archief der Nederlandsch-Portugeesch-Israelietische Gemeente in Suriname, No. 1, residing in the Algemeen RijksArchief, The Hague, but the dates of the entries show that at some point the material was misidentified.

Piedra, “Literary Whiteness,” 295, n. 27.

Blakely, Blacks in the Dutch World, 253-56.

Wim Hoogbergen, The Boni Maroon Wars in Suriname (Leiden, 1990), 37. This Quassie, or Kwasi, had in fact belonged for a period to a Jewish owner, Salomon Pereira. See Natalie Zemon Davis’s beautiful account of the dialogical manner in which the German painter and naturalist Maria Sybylla Merian credited her black and Indian servants and guides in Surinam for their botanical information and included them in the textual recreation of the process of the creation of her scientific knowledge (Davis, Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives [Cambridge, Mass., 1995], 184-87). Davis cites the sixteenth-century Dominican missionary Jean Baptiste Labat, who tweaked one naturalist “for saying he had discovered the secret of an ancient purple dye, when every black fisherman along the Martinique shore knew what mollusk it came from” (ibid., 185). Yet most European naturalists routinely made such informants invisible. In light of all the above, it should be noted that Marcus and Chyet, Historical Essay, and/or its main author, the physician David Nassy, “admit[s] that there have always been in the colony, and [are] even at the present time, some Negroes who have a special knowledge of the medicinal plants of the country, by means of which they have effected cures to the astonishment of the physicians” (159), a formulation that takes back as much as it gives.

Randall M. Falk, Bright Eminence: The Life and Thought of Jacob Rader Marcus (Malibu, Calif., 1994), 47.

Arnold Wiznitzer, Jews in Colonial Brazil (New York, 1960). (Hereafter, the page numbers of quotes from this work are given in the text.) A student of Salo Baron and professor at the University of Judaism in Los Angeles, Wiznitzer had both a Ph.D. from the University of Vienna and a Doctorate in Hebrew Literature from the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (Wiznitzer, The Records of the Earliest Jewish Community in the New World [New York, 1954], title page).

See also Arnold Wiznitzer, “Crypto-Jews in Mexico during the Sixteenth Century” and “Crypto-Jews in Mexico During in the Seventeenth Century,” both in American Jewish Historical Quarterly 51 (1962), and both reprinted in Martin A. Cohen, ed., The Jewish Experience in Latin America: Selected Studies from the Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (Waltham, Mass., 1971).

The 1638 report cited by Wiznitzer was translated from the Dutch into Portuguese by Josè AntÙnio Gonsalves de Mello, Tempo dos Flamengos: InfluÍncia da OcupaÁ…o Holandesa na Vida e na Cultura do Norte do Brasil (Recife, 1987 [1947]), 189: “But the Jewish masters, the letter continues, were preferred over all others, as, not making their blacks work on their sabbaths, they were obligated as well to leave them free on Sundays.”

Wiznitzer also fails to translate Mello’s caveat that the report may be exaggerated. Mello’s footnote reads: “Perhaps there is exaggeration in the relation of preference for Jewish masters. Actually, the blacks in service in the cities have to have enjoyed a certain rest (inasmuch as respect for Sunday was watched following the Acts of the Classe [colonial governing body] of 5 January 1638…), though some Jews made their blacks ‘work in the streets, cut wood, etc., on Sundays’…. Many Jews hired them out to work in the interior, on the engenhos, and in these cases they began to obey the instructions of the masters who engaged them” (Mello, Tempo dos Flamengos, 189, n. 46).

For the original Hebrew, see Meyer Kayserling, “Isaac Aboab: First Author in America,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 5 (1897): 130. All of the Portuguese chronicles agree on the rebel leader’s mulato status.

Daniel M. Swetschinski, “Conflict and Opportunity in ‘Europe’s Other Sea’: The Adventure of Caribbean Jewish Settlement,” American Jewish History 72, no. 2 (Dec. 1982): 236-37.

Yosef Kaplan, “The Curaçao and Amsterdam Jewish Communities in the 17th and 18th Centuries,” American Jewish History 72, no. 2 (1982): 193; Yerushalmi, “Between Amsterdam and New Amsterdam.” It must be noted that Kaplan, an Argentinian-born historian at the Hebrew University, has been one of the few to cite and discuss the various mid-seventeenth-century communal ordinances from Amsterdam that excluded Jewish mulattos from certain ritual honors and communal privileges. See his “Political Concepts in the World of the Portuguese Jews of Amsterdam During the Seventeenth Century: The Problem of Exclusion and the Boundaries of Self-Identity,” in Menasseh ben Israel and his World, Yosef Kaplan, Henry Mèchoulan, and Richard H. Popkin, eds. (Leiden, 1989), and “The Self-Definition of the Sephardic Jews of Western Europe and Their Relation to the Alien and the Stranger,” in Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World, 1391-1648, Benjamin R. Gampel, ed. (New York, 1997), 121-45.

Robert Cohen, “Early Caribbean Jewry: A Demographic Perspective,” Jewish Social Studies 45, no. 2 (Spring 1983). Hereafter, the page numbers of quotes from this work are given in the text.

He leaves out, however, the Jews mentioned in the censuses of Nevis (1707-8) and Curaçao (1709) because there were so few in the former and the latter contained only the adult population (ibid., 133, n. 11).

Many examples could be cited to show that both Jews and non-Jews during the early colonial era were ambivalent about the “racial” status of Jews, especially in northern European contexts. Already in 1691, Francois-Maximilian Mission, one of the influences for Buffon’s Natural History, wrote against such views of Jewish blackness while bolstering in the process the impression that the idea was not uncommon: “Tis also a vulgar error that the Jews are all black; for this is only true of the Portuguese, who, marrying always among one another, beget Children like themselves, and consequently the Swarthiness of their complexion is entail’d upon their whole Race, even in the Northern Regions. But the Jews who are originally of Germany, those, for example, I have seen at Prague, are not blacker than the rest of their countrymen” (Mission, A New Voyage to Italy [London, 1714], vol. 2, 139; cited by Gilman, “Visibility of the Jew,” 3). Note that Buffon leaves the Portuguese Jews black.

Beyond the aspects of physical duress and cruelty, slavery included a panoply of cultural controls and restrictions. In the Caribbean, as elsewhere in the Americas, “laws were passed outlawing assemblies of slaves for any purpose, including religious worship. Slave priests were forbidden to practice. Laws were passed against drums, music at funerals, prayers for the dead, certain African dances, and the composition, possession, sale, or use of fetishes” (Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Social Control in Slave Plantation Societies: A Comparison of St. Domingue and Cuba [Baton Rouge, La., 1996 (1971)], 3940). One would expect Jewish historians to show a more empathetic recognition of slavery’s multidimensional context. In any event, one need only recall the many slave rebellions of the region to suspect the “comparatively tolerant” nature of West Indian slavery.

This is an understandable but unfortunate limitation of many of the otherwise excellent treatments devoted to Jews and black slavery, such as David Brion Davis, Slavery and Human Progress (New York, 1984), 82-101, and “Jews in the Slave Trade,” in CultureFront 1, no. 2 (Fall 1992); Eli Faber, “Slavery and the Jews: A Historical Inquiry,” Occasional Papers in Jewish History and Thought, no. 2, the Hunter College Jewish Social Studies Program (Hunter College of the City University of New York, 1994), and Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade; and Saul S. Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade (New Brunswick, N.J., 1997). Faber’s failure to treat master-slave relations in his book is particularly disappointing insofar as its title seems to promise inclusion of just such coverage.

In two of his earlier works, Jews merit only the briefest coverage, and even then mostly as an incidental matter, to illustrate the origins and development of Christian attitudes (Davis, Problem of Slavery, 63-66, 98-101, 451, and The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823 [Ithaca, N.Y., 1975], 532-37). Perhaps the increased interest in Jews anti slavery correlates to Davis’s conversion to Judaism. Certainly since the publication of the Nation of Islam’s The Secret Relationship, Davis has taken upon himself the task of defending Jews against the charges made there and by other black nationalists that Jews were the main fomenters of the Atlantic slave trade (see, for instance, Davis, “Jews in the Slave Trade,” reprinted in Salzman and West, Struggles in the Promised Land). I want to clarify the specificity of my remarks: I have the utmost respect for Davis’s work (and that of all the scholars I treat); I have used it and learned from it greatly. My own work would not be possible without it. David Brion Davis, in the little contact that I have had with him, has been congenial, helpful, and supportive.

Obviously the specific charges that Jews instigated and dominated the trading of Africans needed rebuttal, something I neither dispute nor minimize. But these charges marked an acute crisis; a more lingering condition lay in the lack of scholarly interest in exploring black-Jewish relations beyond the contexts generated by the polemic. Davis’s defensive posture, it should he noted, came several years before the Nation of Islam’s pseudo-scholarly work.