Showdown at Waxahachie

“The robbery of our people in neighborhood stores, the paying of higher prices for inferior merchandise; the insults Blacks experience from storekeepers are among the daily indignities we suffer.”

—Bro. Jabril Muhammad, This Is The One

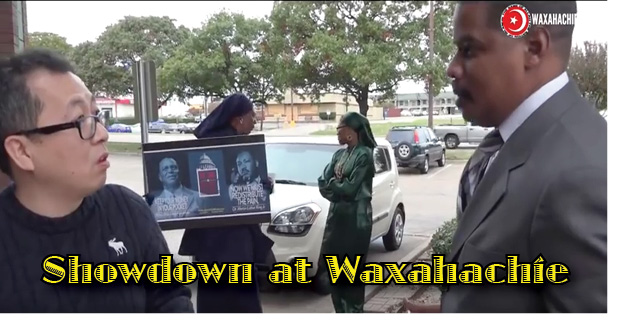

A beauty supply store in Waxahachie, Texas, is not the place one would expect to be Ground Zero in the “Redistribute the Pain” campaign to control the Black dollar. But something powerful occurred in this small town outside Dallas when the Nation of Islam Study Group there heard The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan implore Blacks to support their own businesses and institutions to help redress the many ills we face in America.

Waxahachie (pronounced Wocks-a-ha-chee) has one of the 9,000 Korean-owned beauty supply stores across America exploiting a nine-billion-dollar Black hair care market. The town also has a Black-owned store named Empress Beauty Supply, but there are only a few hundred Black-owned beauty supply stores in America. As with most communities, the Korean store dominates the local market because the Black customers are often unaware that an alternative Black-owned business exists. The Koreans adorn the outside of their stores with movie poster-size photographs of beautiful Black women, as a fisherman baits his line with fat juicy worms. As a result, the Korean store’s customers are almost 100 percent Black, but once inside they find not a single Black employee, and not a single product made by a Black manufacturer, and not a chance in hell that the money spent will ever help build or strengthen the local Black community.

The Waxahachie Muslims, led by their intrepid study group coordinator Malik Muhammad, sought to remedy this unacceptable trade imbalance by informing the neighborhood of the Black alternative just down the street. They set up an information station on a public sidewalk near the Korean store and asked the steady stream of Black hair care customers to simply consider the Black-owned vendor. The day’s events were captured on film and posted on YouTube as one by one Black men and women seemed happy—even relieved—to know there was a more equitable destination for their Black dollars. Most of them, after receiving the information, got right back in their cars and shopped at Empress, where the sister proprietor—who actually has Black hair and skin—conscientiously employs Blacks and has a full line of hair and skin care products from Black manufacturers.

Needless to say, the Korean merchant quickly noticed the reduction in its customary Black foot traffic. In his broken English-Korean accent he accused the Muslims of injustice: “I think this is not right sir.” But it was hard indeed for a Korean to convince a wide-awake Black man that following an age-old Korean economic empowerment practice was “not right.” Unashamed of his own hypocrisy, the Korean called in the police, which he apparently believed should enforce his Korean right to keep Black wealth flowing into Korean pockets. But the law clearly was on the side of the NOI. The sidewalk was public property, on which even Black people had a right to peaceably gather to discuss their multi-faceted forms of their own oppression. Despite the best efforts of the Korean, the white police officer was powerless to intercede.

As the Korean fumed, the Muslims turned back to their educational mission. One by one, two by two, and ten by ten, the newly notified Blacks headed over to Empress, which reported that business increased fifty percent in the first week, and 100 percent the next. It must have been disconcerting for the Koreans to see 90 Waxahachie Black consumers acting like Koreans. But the fact is that Black stores have no Korean customers; nor do the Korean stores purchase from Black suppliers. It is a totally one-way exploitative commerce.

And it has been that way since the Koreans arrived in America about a century ago. The first wave came to be laborers on Hawaii’s sugar plantations. Some of them made their way to Dallas, where they gathered in the northwest part of the city, an area that became known as Koreatown. They fostered a collaborative entrepreneurial culture and established banks and business associations. They organized rotating credit associations that financed family-based businesses, which grew into formidable kinship networks. So powerful is their prowess in business that Dallas street signs have symbols of the national flag of South Korea directing people to “Asian Trade District.” Here, there are no Black businesses sharing in the commercial activity—some Chinese and Japanese have been allowed, but Blacks are kept out.

Like the Jews before them, Koreans (and Asians in general) have sought out Black population centers to set up their most profitable shops and services. They are totally dependent on Black economic illiteracy for their livelihoods. It is this specific economic ignorance that they actually banked on and invested in. Nine thousand shops did not pop up in Black communities without careful analysis and supreme confidence that Blacks would never wake up to their own economic power. The Waxahachie Muslims did more than redirect a few customers to a Black business, they upset a multi-billion-dollar race-exploitation scheme that ALL immigrants to America have relied on for 400 years.

Meanwhile, the Waxahachie Korean merchant was shaken, but not down. He called in the all-time world economic grandmasters—the Jews. Long ago Jewish immigrants started in the South as peddlers, and it was they who wrote the book on controlling the Black dollar. In Waxahachie they moved from petty commerce to become landlords, who now collect rent from the Asian shop owners. When the Jewish strip-mall owners arrived to threaten the Muslims, they reacted typically: they called our sisters and brothers “Haters” as they called the police back to the store.

But Dallas Jews should be careful about who they call haters. Back in the 1920s Jews coexisted amicably with the Ku Klux Klan. Jewish retail mogul Alex Sanger shared the stage on “Klan Day at the Texas State Fair.” When Fort Worth’s Rabbi G. George Fox left the city in 1923, the Chamber of Commerce arranged a farewell luncheon, the head of the local Ku Klux Klan presiding. The rabbi had many Klan acquaintances and treated the terrorists “as the friends and associates they were,” according to the NOI book, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews. The local Jewish Monitor newspaper, which Rabbi Fox edited, declared that “the alleged prejudice against Jews in [the KKK] is exaggerated….[they] are also some of my best friends.”

The Jewish property owners ultimately had to bow to the law that said the Muslims were perfectly within their rights to educate their own people about their own economic reality.

The Waxahachie Muslims must be respected for their intelligent activism. They follow a grand tradition of Black protest that The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan has once again brought to our view. The Muslim organizers of the great Harlem Jobs campaign in the 1930s stood in front of Jewish stores like Koch’s, Sticklers, Weisbecker’s, and Blumsteins and demanded that they hire Blacks, with the cry of “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work.” They opened up hundreds of jobs for Black people in stores that formerly had “no-Blacks” hiring policies. Since the 1980s, disrespectful Korean merchants have faced Black boycotts in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, DC, and Berkeley, California.

But the Waxahachie Muslims are set apart from all these actions because they also followed another maxim of The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad: “Don’t criticize a dirty glass, set a clean one up beside it. The people will know which one to drink from.” The Empress Beauty Supply represents a clean glass in Waxahachie for Black consumers to drink from, but the lesson is that Blacks MUST set up 9,000 more such establishments from coast to coast if they are serious about true justice.

Ironically, a Jewish filmmaker named Aron Ranen has documented the marginalization of Black entrepreneurs in the hair care industry, and he offers some important advice about how Blacks might capitalize on the Waxahachie example. Ranen says he wants to see “100 black-owned stores opening up right next to Korean stores [and] a boycott until the Korean stores accept at least 20% black-owned manufactured products. Then we are talking about money in the community.” He says, “There are people on Wall Street who can fix this in a minute and create some kind of dynamic kind of stock offering, completely above the board to open and fund [Black] stores and give out shares.”

Good idea. Waxahachie has proved that Black consumers do indeed want a Black place to spend their hard-earned Black dollars, and Black hair and beauty products are a perfect way to demand Justice Or Else.